FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797 – 1828): Winterreise, D. 911—(1) Zvi Emanuel-Marial, male alto; Philip Mayers, piano [Recorded in b-sharp Studio, Berlin, Germany, on 17, 21, and 23 October 2013; Thorofon CTH2615; 1 CD, 67:36; Available from ClassicsOnline, Amazon, jpc, and major music retailers] and (2) Daniel Behle, tenor; Oliver Schnyder Trio [Recorded in Zürich, Switzerland, 15 – 19 June 2013; Sony Classical 88883788232; 2 CDs, 125:56; Available from Amazon, jpc, iTunes, and major music retailers]

FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797 – 1828): Winterreise, D. 911—(1) Zvi Emanuel-Marial, male alto; Philip Mayers, piano [Recorded in b-sharp Studio, Berlin, Germany, on 17, 21, and 23 October 2013; Thorofon CTH2615; 1 CD, 67:36; Available from ClassicsOnline, Amazon, jpc, and major music retailers] and (2) Daniel Behle, tenor; Oliver Schnyder Trio [Recorded in Zürich, Switzerland, 15 – 19 June 2013; Sony Classical 88883788232; 2 CDs, 125:56; Available from Amazon, jpc, iTunes, and major music retailers]

Since the publication of the cycle in 1828, Franz Schubert’s Winterreise has been one of the benchmarks by which a singer’s fluency in Lieder repertory has been assessed. The array of voices by which the cycle has been sung and the range of interpretations to which the individual Lieder in Winterreise have been subjected are exceptionally broad. Winterreise on records will likely always be associated in the minds of many listeners, even those who never heard him otherwise, with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, but among male interpreters of the cycle memorable accounts have been recorded by low voices as diverse as Gerhard Hüsch, Karl Schmitt-Walter, Hans Hotter, Kurt Moll, and Hermann Prey, as well as by tenors such as Peter Anders, Anton Dermota, Julius Patzak, Sir Peter Pears, Ernst Haefliger, and Ian Partridge. The first female singer to set her sights on Winterreise—in near-complete form on records, at least—seems to have been the magnificent German soprano Lotte Lehmann, whose idiosyncratic 1940 – ‘41 recording with her regular accompanist, Paul Ulanowsky, paved the way for notable later efforts by Lois Marshall, Brigitte Fassbaender, Christa Ludwig, Christine Schäfer, and Alice Coote. [Sadly, Elena Gerhardt’s famed interpretation of the cycle was not preserved in full.] The autograph keys suggest that Schubert intended Winterreise for tenor voice, but his fondness for the baritone voice of his friend Johann Michael Vogl is extensively documented. Vogl was the foremost interpreter of Die Schöne Müllerin, Schubert’s earlier cycle utilizing poetry by Wilhelm Müller, in the years between the completion of the cycle and his death in 1840, and though his relationship with Winterreise is less known to history he sang the complete cycle to great acclaim shortly before he died on the twelfth anniversary of Schubert’s death. In the generations since the first publication of Winterreise in two parts, a near-infinite progression of transpositions has altered the individual songs and the cycle as a whole. The Winterreisen on these new releases from Thorofon and Sony Classical present new perspectives on this endlessly enchanting trek through love, uncertainty, and resignation. Whatever novelties a recording of Winterreise proposes, it is the singing that must ultimately be the raison d’être. The voice is the only conduit for the emotional deluge of this music: without it, where can a Winterreise go?

However the twenty-four Lieder in Winterreise are transposed, arranged, re-ordered, or reconfigured, they are fraught with difficulties for any singer regardless of Fach. Many singers have discovered that approaching Winterreise as an extended operatic scena is folly, as is tiptoeing through the music as though each Lied is a holy relic. It is a cycle that requires attention to its basic construction and cognizance of the ways in which Schubert utilized restrained musical structures to further the dramatic impetus portrayed in the texts. As an exhibition of unexaggerated sentiments expressed in song, Israeli male alto Zvi Emanuel-Marial’s Winterreise on Thorofon is a very personal journey that never descends into tasteless hyperbole. Possessing a lovely, soft-edged timbre, Mr. Emanuel-Marial must be applauded for singing the cycle without taking shortcuts or cautiously crawling through the music. Ably accompanied by Australian pianist Philip Mayers, whose playing instinctively matches the emotional nuances of his colleague’s interpretations of each song, the singer builds great cumulative force by approaching each song in succession with clear-headed simplicity. This is not a reading of grandiose philosophical aggrandizing: instead, it is a look—indeed, almost an intrusion—into a bare but not despondent explication of sentiments too ambivalent for expression via words alone.

Mr. Emanuel-Marial opens his journey through Winterreise with an especially lovely account of 'Gute Nacht,' and there is a simple, boyish fascination at the heart of his voicing of 'Wetterfahne.' In 'Gefrorne Tränen' and 'Erstarrung,' the tessitura makes demands that Mr. Emanuel-Marial's voice can meet only with discernible effort, but what his performance costs him in the expenditure of vocal capital is handsomely repaid by the sagacity of his elucidation of text. His singing of 'Der Lindenbaum,' a song too often flippantly delivered, is endearing, the warmth of his enunciation of the vowels combining with the fluidity of Mr. Mayers’s pianism with rare grace. The imagery of ‘Wasserflut,’ ‘Auf dem Flusse,’ and ‘Rückblick’ is powerfully conveyed by Mr. Emanuel-Marial’s unaffected diction, and the stark but soft-edged realism of his performances of ‘Irrlicht,’ ‘Rast,’ and the sublime ‘Frühlingstraum’ is very effective. ‘Einsamkeit’ is executed with bleakness, all color drained from the voice.

The anxiety of hearing the distant post-horn and the bitter disappointment of realizing that it heralds no news from the object of the narrator’s passion are palpably imparted by Mr. Emanuel-Marial’s agitated singing of ‘Die Post,’ and the restlessness of ‘Der greise Kopf’ finds a meaningful outlet in the singer’s and Mr. Mayers’s rhapsodic performance. The growing perceptions of natural phenomena as harbingers of psychological upheaval in ‘Die Krähe,’ ‘Letzte Hoffnung,’ ‘Im Dorfe,’ and ‘Der stürmische Morgen’ are pointedly translated into sound by Mr. Emanuel-Marial’s sparse vocalism. The taunting beacons of ‘Täuschung’ and ‘Der Wegweiser’ are decried with fervor, and the deceptive haven encountered in ‘Das Wirtshaus’ is denounced with heartbreaking hopelessness. The biting cold of the wind and snow in ‘Mut!’ shiver in the voice and piano, and the symbolic trinity of ‘Die Nebensonnen’ draws from singer and accompanist an expression of spellbound religiosity. There is unmistakable significance to Mr. Emanuel-Marial’s pronouncement of the final line of ‘Der Leiermann,’ ‘Willst zu meinen Liedern deine Leier dreh’n?’: the question is delivered directly to the listener, as if to say, ‘Will you walk with me, wherever this journey leads?’ The ambiguity in Mr. Emanuel-Marial’s tone, poised between romanticized masculinity and poetic androgyny, facilitates a construal of Winterreise that reverberates with melancholy and manic energy, and the singer and his accompanist give a performance of the cycle that is memorable for far more than its unconventionality.

As in his Capriccio recording of Brahms's Die schöne Magelone, tenor Daniel Behle offers a pair of performances, one of Winterreise in its traditional form and another in an intriguing adaptation of his own composition. Many—perhaps most—of the instrumental arrangements of Winterreise that have been attempted in past have been egotistical endeavors, the primary goals of which were not to pay homage to Schubert’s genius but to provide opportunities for ambitious musicians to hone their compositional skills by tinkering with music of proven appeal. This emphatically is not the case with Mr. Behle’s reimagining of Winterreise. An artist of uncompromising integrity, Mr. Behle has looked very deeply into the most minute details of Schubert’s settings of Müller’s texts and extracted threads that he then reassembled in expanded form, neither disrupting the lyrical flow of Schubert’s thematic development nor imposing harmonic complexities that the basic structures of the music cannot sustain. This also is not vapid salon music, however, and it is not a wholesale restatement of Schubert’s piano accompaniments with decorative violin and cello obbligati. Instead, Mr. Behle has essentially transformed Winterreise into profoundly emotive chamber music for quartet, with the voice being the instrument charged with speech. Hearing him sing the cycle in this form, it seems virtually impossible that any other artist could do it justice, but Mr. Behle’s arrangement is one of a handful of loving adaptations that deserves attention from other singers and musicians undertaking Winterreise.

Whether accompanying Mr. Behle in the traditional performance of the cycle or anchoring the trio in the tenor’s arrangement, pianist Oliver Schnyder is an attentive, unflappable source of grounded strength who plays as though he were singing the Lieder himself. Reveling in Schubert’s sometimes very wittily contrasted harmonies, he collaborates with Mr. Behle in the adoption of tempi that enable rhythmic precision without inhibiting dramatic flexibility. Violinist Andreas Janke and cellist Benjamin Nyffenegger play entrancingly, their phrasing informed by obviously multi-layered comprehension of the texts and an uncanny sensitivity to the subtleties of Mr. Behle’s interpretations. Individually and in ensemble, the instrumentalists respond to one another, to the singer, and to the ever-changing facets of Schubert's music with consummate artistry and the thrill of exploration missing from so many performances of the cycle.

Solely in terms of vocalism, Mr. Behle is among the most successful performers of Winterreise on disc. He shares with Mr. Emanuel-Marial an unwonted freshness of approach, a sense of having come to the music without preconceptions or prejudices. It is only natural that a singer should give of his best when performing music that he arranged, but Mr. Behle possesses an ideal voice for Schubert’s vocal lines. His burnished lower register is heard to potent effect in the opening ‘Gute Nacht,’ both in the ‘traditional’ performance and in that of his arrangement. In fact, the singer’s exegesis of the songs remains strikingly consistent in both performances. The squeaking of a rusted weathervane is evoked in Mr. Behle’s ‘Wetterfahne,’ particularly in his own arrangement, and the crystalline beauty of tone that he devotes to ‘Gefrorne Tränen’ is inspiring. His singing of ‘Erstarrung’ has a deadened quality, the voice hollow with the disenfranchisement of a man who finds no trace of his beloved. Both with piano and with the trio, his ‘Der Lindenbaum’ glows with serene recognition. Like Mr. Emanuel-Marial, he unleashes startlingly vital tone painting in ‘Wasserflut,’ ‘Auf dem Flusse,’ and ‘Rückblick,’ and his handling of ‘Irrlicht’ exudes confusion and chagrin. Mr. Behle makes of ‘Rast,’ ‘Frühlingstraum,’ and ‘Einsamkeit’—three of the finest songs in the cycle—a strangely vivid triptych, closing the first half of Winterreise with an acutely erudite, almost sensual voicing of the line, ‘War ich so elend nicht.’

Mr. Behle begins ‘Die Post’ with a burst of optimism that quickly fades into anguish. A marvel of Mr. Behle’s performance is that he heightens the impact of the desolation of the text by intensifying the attractiveness of his singing. The prevailing sentiment of his account of ‘Der greise Kopf’ is the suggestion that suffering purifies human desires, and he transforms this conceit into an acceptance of the conflicting implications of nature manifested in ‘Die Krähe,’ ‘Letzte Hoffnung,’ ‘Im Dorfe,’ and ‘Der stürmische Morgen.’ The flickering light mentioned in Müller’s text in ‘Täuschung’ shines in Mr. Behle’s voice and in the instruments that support it. His wide-eyed contemplation of nature’s trickery in ‘Der Wegweiser’ contrasts with his recognition of the pain of human denial in ‘Das Wirtshaus.’ ‘Mut!’ bristles with irony, but, like Mr. Emanuel-Marial, he lends ‘Die Nebensonnen’ an atmosphere of hard-won tranquility. In the final song, ‘Der Leiermann,’ the lingering impression of Mr. Behle’s interpretation differs markedly from Mr. Emanuel-Marial’s: rather than seeking the companionship of the listener, Mr. Behle addresses his concluding query to himself, quietly appraising the ability of the narrator of Winterreise to carry on. Whether accompanied by piano in Schubert’s settings or by piano trio in his own noteworthy arrangement, Mr. Behle’s Winterreise is one of struggle endured with insurmountable grace.

With so many superb song cycles, especially those by Czech, Polish, and Spanish composers, still virtually unknown beyond the ranks of the most conscientious connoisseurs of Art Song, why does Franz Schubert’s Winterreise remain a central pillar in the temple of song? Why, nearly two centuries after the shy composer’s death, are his songs still the standards by which singers’ abilities as Lieder interpreters are measured? In her book More Than Singing, the soprano Lotte Lehmann wrote that in Winterreise ‘the lover has come to realize the worthlessness of his beloved and knows at last that the love which was the greatest experience of his life, has been squandered on one who was incapable of appreciating the unique gift of true love and faith.’ It is the dichotomy of expressing the narrator’s realization of that worthlessness and maintaining at least a muted faith in love that makes performance of Winterreise one of the most fearsome experiences in lyric art. Each in his own way, Zvi Emanuel-Marial and Daniel Behle make the journey hauntingly, proving anew that the spectrum of emotions explored in the songs of Winterreise is limited only by the imaginations of the artists who perform them.

Franz Peter Schubert (31 January 1797 – 19 November 1828)

Franz Peter Schubert (31 January 1797 – 19 November 1828)

RICHARD WAGNER (1813 – 1883): Der fliegende Holländer—

RICHARD WAGNER (1813 – 1883): Der fliegende Holländer— Traft ihr das Schiff: Anja Kampe as Senta in Tim Albery’s production of Der fliegende Holländer at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 2011 [Photo by Mike Hoban, © The Royal Opera House]

Traft ihr das Schiff: Anja Kampe as Senta in Tim Albery’s production of Der fliegende Holländer at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 2011 [Photo by Mike Hoban, © The Royal Opera House] JOHANN ADOLF HASSE (1699 – 1783): Siroe, rè di Persia (1763 Dresden version)—

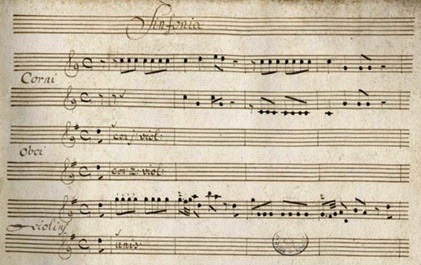

JOHANN ADOLF HASSE (1699 – 1783): Siroe, rè di Persia (1763 Dresden version)— Hasse by Hand: the manuscript of the Sinfonia from the 1733 version of Hasse’s Siroe, re di Persia in the collection of the Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Stats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden

Hasse by Hand: the manuscript of the Sinfonia from the 1733 version of Hasse’s Siroe, re di Persia in the collection of the Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Stats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden GIOVANNI BONONCINI (1670 – 1747), GIOVANNI BATTISTA COSTANZI (1704 – 1778), FRANCESCO FEO (1691 – 1761), NICOLA PORPORA (1686 – 1768), DOMENICO SARRO (1679 – 1744), ALESSANDRO SCARLATTI (1660 – 1725), and LEONARDO VINCI (1690 – 1730): Arias for Domenico Gizzi – A star castrato in Baroque Rome—

GIOVANNI BONONCINI (1670 – 1747), GIOVANNI BATTISTA COSTANZI (1704 – 1778), FRANCESCO FEO (1691 – 1761), NICOLA PORPORA (1686 – 1768), DOMENICO SARRO (1679 – 1744), ALESSANDRO SCARLATTI (1660 – 1725), and LEONARDO VINCI (1690 – 1730): Arias for Domenico Gizzi – A star castrato in Baroque Rome—

PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY / Пётр Ильи́ч Чайко́вский (1840 – 1893): Iolanta (Иоланта), Op. 69—

PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY / Пётр Ильи́ч Чайко́вский (1840 – 1893): Iolanta (Иоланта), Op. 69— Coming soon to a Forbidden City near you: soprano Othalie Graham, leading lady of Opera Carolina’s 2015 production of Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot [Photo © Othalie Graham; used with permission]

Coming soon to a Forbidden City near you: soprano Othalie Graham, leading lady of Opera Carolina’s 2015 production of Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot [Photo © Othalie Graham; used with permission]  Principessa altera: soprano Othalie Graham in the title rôle of Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot [Photo used with permission]

Principessa altera: soprano Othalie Graham in the title rôle of Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot [Photo used with permission] FRANCESCO MARIA VERACINI (1690 – 1768): Adriano in Siria—

FRANCESCO MARIA VERACINI (1690 – 1768): Adriano in Siria—