JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685 – 1750) – Sonatas for Flute and Harpsichord, BWV 1020, 1030 – 1032; Partita for Solo Flute, BWV 1013: Joshua Smith, flute; Jory Vinikour, harpsichord [recorded in First Baptist Church of Greater Cleveland, OH, during December 2008; DELOS DE 3402]

The visceral appeal of music is a marvel that cannot be fully explained with even the most eloquent words. Physiologically, it is a function of synapses being engaged at an almost primordial level, of extraordinarily complicated series of responses to aural stimuli. The metaphysics of music, though less tangible in a scientific sense, are more readily comprehensible. A critical element of the natural grandiloquence of a memorable musical experience is surely derived from the fact that at its heart music is a triumph over the unexpected, over the listener’s fear of disappointment within the limitations of individual exposure. Because it requires both a medium and an audience, music is never truly solitary and is always new.

Recordings are technological witnesses to listeners’ fears of musical betrayal. There are those instances in which a listener, having lavished affection on an artist’s recordings, attends a performance by that artist and feels the excruciating deflation of a genuine respect when the artist in the flesh is not an unflawed copy of the artist familiar from records. Conversely, there are artists of whose prodigious talents in live performance there are only glimpses on recordings. Invaluable as efforts at preservation in the case of towering individual interpretations and conservation in the case of works that teeter at the edge of obscurity are, recordings are inevitably perilous for artists. Making a superb recording is not the same enterprise as giving a memorably fine performance before an audience. It is unfortunately frequent that audiences and listeners discern this before the artists themselves fully fathom the precariousness of their good intentions.

There is no shortage of recordings of the four sonatas for flauto traverso and cembalo offered on this disc by Joshua Smith and Jory Vinikour, with a multitude of versions from both popular concert flautists playing modern flutes and period-performance specialists playing Baroque instruments. It would be disingenuous to suggest that these sonatas, even with their considerable discography, are standard-repertory fodder, however. Perhaps, like so many Baroque works that have been revived during the past quarter-century, these sonatas – gems of form that reveal Bach at his apex as a composer of chamber music – have merely awaited discovery by artists who, in performance and on records, not only understand without exaggerating their musical significance but also regard them as their composer must have intended, as vehicles for artistic collaboration and exchange of the highest order.

Without understating the impact of the technical brilliance of the playing, it was obvious to the audience for their December 2008 recital [reviewed on this site] that followed the recording sessions that produced this disc that Mr. Smith shared with Mr. Vinikour completely natural affinities for the collaboration and exchange required by this music, along with an unforced artistic partnership that made their playing seem almost to emanate from two bodies drawing upon one soul. In the case of that magical evening, it is not merely a poetic conceit to suggest that the soul that inhabited those two artists was Music itself.

Listening to this disc, not as a souvenir of that recital but as a performance with its own unique provenance, it is difficult to keep in mind the work that both artists devoted to this project. Nothing is shirked, no challenge is met with anything other than absolute mastery, and yet the music-making is of such quality that there is no sense of effort. For artists who enjoy the levels of virtuosity attained by Mr. Smith and Mr. Vinikour, the supreme difficulties of the music are in its interpretation. Nevertheless, this appearance of ease should not distract from the incredible feats of technical execution that fill this recording.

The disc opens with the B-minor Sonata (BWV 1030), perhaps the most technically demanding but also rewarding of Bach’s sonatas for flute. Questions of authenticity surround much of the extant flute music in the catalogue of Bach’s output, but the B-minor sonata is indisputably the work of Johann Sebastian Bach. In both this sonata and the A-major sonata (BWV 1032), the harpsichord lines are composed in full, a departure from the continuo style of accompaniment typically employed in sonatas for solo instruments by Bach and his contemporaries. Though limiting the keyboardist’s opportunities for extemporaneous ornamentation, this structure elevates the harpsichord’s music to a stature equivalent to that for the flute, creating a true partnership that must be maintained by both players in order for the music to make its full effect. The rare grace of the collaboration between Mr. Smith and Mr. Vinikour here bears its sweetest fruit. With every technical requirement met, these artists explore the emotional niches of this sonata, revealing harmonic progressions that suggest psychological insights one might expect to encounter in the chamber music of Beethoven or Brahms.

The G-minor Sonata (BWV 1020) that follows is somewhat dubious in terms of both authorship and instrumentation. There exists a version of the score which features a solo violin rather than a flute, and some scholars have suggested (though without offering any compellingly concrete evidence) that the sonata is partially or wholly the work of Bach’s son Carl Philipp Emanuel. The sonata is a fine work, whatever its origins may be, and it receives a lovely performance from Mr. Smith and Mr. Vinikour.

The E-flat major sonata (BWV 1031) has also been subject to conjecture concerning Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach having lent his hand to its composition, but the considerable quality of the music has ensured that the sonata has remained in the flute canon. In this sonata, the harpsichord part is conceived more in the traditional continuo fashion of Bach’s time, but the roles are equalized to a great degree in the final movement. It is the second movement, the Siciliana, that is truly exquisite, however, and Mr. Smith plays the flute’s expansive melodic lines with an ideal blend of freedom and control. In this context, the Siciliana seems almost a vocalise, the flute taking on the qualities of a delightfully pure, melancholic voice. The final movement is underlined by a sense of joy that is apparent in the performance it receives.

The last work on this disc is the A-major Sonata (BWV 1032), another piece that is slightly problematic. Ironically, BWV 1032 was the only one of Bach’s flute sonatas that was preserved in Bach’s autograph manuscript, but this fell victim like so many priceless works of art to World War II. Forty-six bars from the beginning of the first movement are thus lost to modern musicians, most of whom perform editions that employ a reconstruction utilizing existing thematic material. Returning to the structure in which the harpsichord part is fully composed, Mr. Vinikour is given (especially in the opening movement) terrific opportunities to display his impressive skills for powerful, theatrical playing. Pursuing melodic paths that are different but always complementary, both flautist and harpsichordist take parallel journeys that illuminate their individual strengths as prodigiously-talented musicians, their seemingly unflappable instincts for chamber playing, and Bach’s innate genius for injecting even small musical gestures with grandeur.

Mr. Smith completes the disc with a performance of the A-minor Partita for solo flute (BWV 1013). Consisting of four movements derived from dance forms popular in the Baroque era (Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, and Bourée Anglaise), the Partita offers a compact but comprehensive treatise on Bach’s style of composition for the flute. Phrases of serene beauty are joined comfortably with passages of bravura intensity, all of them played by Mr. Smith with his customary ‘singing’ tone and attention to detail. It is worth restating in the context of the Partita that, when listening to this disc, it is easy to forget what a formidable technique is required in order to play the music at this level.

Thankfully, the flute sonatas of Johann Sebastian Bach are sufficiently familiar to musicians and music lovers that Mr. Smith and Mr. Vinikour are spared the daunting task of rehabilitating them. What they achieve in this recording is the revitalization of the music in a way that, rather than altering the presentation of the works, alters the listener’s perceptions of them. Listening to this recording, there is the sense not of hearing these sonatas again but of hearing them anew, in a performance that is appropriate to the period in which they were composed but not encumbered by it. It is Baroque, of course, but Mr. Smith and Mr. Vinikour allow the listener to appreciate through their playing that this is, foremost, music. The recording is, just as their Cleveland recital was, a complete triumph over the unexpected.

![Jory Vinikour [Photo by Kobie van Rensburg] Jory Vinikour [Photo by Kobie van Rensburg]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/_lJ800S4CaE8/SudH3jw898I/AAAAAAAAAf4/xoWp5L1kaqo/Jory%20Vinikour%201%20by%20Kobie%20van%20Rensburg%2C%202008%5B11%5D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![Andrew Foster-Williams [Photo by Marco Borggreve] Andrew Foster-Williams [Photo by Marco Borggreve]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/_lJ800S4CaE8/SuNANlQbw3I/AAAAAAAAAew/1lmHhZgPrlg/AFW_Marco_Borggreve%5B7%5D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![Andrew-Foster Williams as Leone at Washington National Opera [Photo by Karin Cooper] Andrew-Foster Williams as Leone at Washington National Opera [Photo by Karin Cooper]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/_lJ800S4CaE8/SuNAN0kHZcI/AAAAAAAAAe0/FyaE71RUHHw/TAMERLANO_0408_9web%5B6%5D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![Ingrid Perruche as Mélisande and Andrew-Foster Williams as Golaud [Photo by Belinda Lawley] Ingrid Perruche as Mélisande and Andrew-Foster Williams as Golaud [Photo by Belinda Lawley]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/_lJ800S4CaE8/SuNAONLW8YI/AAAAAAAAAe4/2PBb-H_2vm0/Pelleas_et_Melisande_2%5B6%5D.jpg?imgmax=800)

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770 – 1827) – Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125: J. Sutherland, N. Procter, A. Dermota, A. van Mill; Choeur du Brassus/André Charlet, Choeur des Jeunes d’Église National de Vandoise; L’Orchestra de la Suisse Romande; Ernest Ansermet [recorded in Victoria Hall, Geneva, during April 1959; DECCA Eloquence 480 0397 (Australia)]

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770 – 1827) – Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125: J. Sutherland, N. Procter, A. Dermota, A. van Mill; Choeur du Brassus/André Charlet, Choeur des Jeunes d’Église National de Vandoise; L’Orchestra de la Suisse Romande; Ernest Ansermet [recorded in Victoria Hall, Geneva, during April 1959; DECCA Eloquence 480 0397 (Australia)]

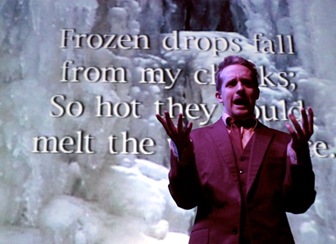

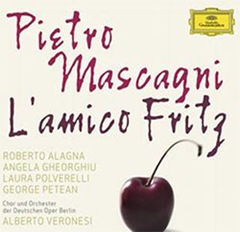

PIETRO MASCAGNI (1863 – 1945): L’Amico Fritz – R. Alagna (Fritz Kobus), A. Gheorghiu (Suzel), L. Polverelli (Beppe), G. Petean (David), Y. Kang (Federico), H.-W. Lee (Hanezò), A. Fernández (Caterina); Chor und Orchester der Deutschen Oper Berlin; Alberto Veronesi [recorded during a concert performance at the Deutsche Oper Berlin on 20 September 2008; DGG 477 8358 9]

PIETRO MASCAGNI (1863 – 1945): L’Amico Fritz – R. Alagna (Fritz Kobus), A. Gheorghiu (Suzel), L. Polverelli (Beppe), G. Petean (David), Y. Kang (Federico), H.-W. Lee (Hanezò), A. Fernández (Caterina); Chor und Orchester der Deutschen Oper Berlin; Alberto Veronesi [recorded during a concert performance at the Deutsche Oper Berlin on 20 September 2008; DGG 477 8358 9]