JEAN SIBELIUS (1865 – 1957): Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Opus 39 — Orchestre Métropolitain de Montréal; Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conductor [Recorded in Maison symphonique de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada, in October 2018; ATMA Classique ACD2 2452; 1 CD, 41:06; Available from ATMA Classique, Naxos Direct, Amazon (Canada), Amazon (USA), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

JEAN SIBELIUS (1865 – 1957): Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Opus 39 — Orchestre Métropolitain de Montréal; Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conductor [Recorded in Maison symphonique de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada, in October 2018; ATMA Classique ACD2 2452; 1 CD, 41:06; Available from ATMA Classique, Naxos Direct, Amazon (Canada), Amazon (USA), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

It is unlikely that any serious musician pursuing a career in North America has escaped being regaled with the adage that stipulates that the path to New York City’s Carnegie Hall, revered as a sort of Mecca for concert artists, is peregrinated with practice, practice, practice. The peril of conventional wisdom is that it is often more conventional than wise, but few musicians with genuine affection for their work would contradict the assertion that, even for artists with extraordinary natural talent, the only true means of achieving greatness is a continuous process of honing, refining, and renewing one’s craft.

Assessing artists’ significance is an inherently subjective undertaking, but there are finite criteria that determine an instrumentalist’s qualification for consideration. Any piece of music presents its own unique challenges, and a musician’s technical proficiency either is or is not equal to the music’s demands. There are also appraisable aspects of a conductor’s artistry, among which baton technique is perhaps the most visible, but evaluation of a conductor’s importance is affected to an even greater extent than analysis of an instrumentalist’s noteworthiness by intrepretive acuity.

A professional orchestra deserving of that designation can maintain musical integrity without the guidance of a conductor, but the reputation of the personage on the podium is founded upon subtleties that are perceived and esteemed differently by each listener. The physical dimension of conducting notwithstanding, a conductor’s success is innately ephemeral. Colloquially, it might be said that the proof of a conductor’s merit is in the hearing. Hearing this ATMA Classique recording of Jean Sibelius’s First Symphony, expertly engineered to faithfully reproduce the rich acoustic of Montréal’s Maison symphonique, is a gratifyingly visceral experience. The performance exudes a vitality that is achieved in the recording studio only by a conductor who respects the music and commands the respect of his musical collaborators. Are those not two crucial measures of a conductor’s artistic value?

At an age at which some of the most admired conductors of previous generations essentially remained apprentices, Québécois conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin has built a career that has already encompassed leadership positions with the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, The Philadelphia Orchestra, and The Metropolitan Opera, with the last of which institutions he is completing his first season as Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director with performances of Francis Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites. It is in his capacity as Music and Artistic Director of his native city’s Orchestre Métropolitain that he leads this performance of Sibelius’s Opus 39 Symphony No. 1 in E minor.

Nézet-Séguin has been fortunate to inherit from his predecessors resilient orchestras, and his effective, nurturing direction has bolstered the standards of excellence achieved by Orchestre Métropolitain. The performance on this disc conveys an engrossing sense of occasion, orchestral balances meticulously matched to the music and the space in which it was recorded. The understated rhythmic precision that has become a hallmark of Nézet-Séguin’s conducting is particularly apparent in this performance: at the core of even the most rhapsodic passages is a robust beat that intensifies the continuity of the conductor’s handling of this score.

Born in the Finnish city of Hämeenlinna in 1865, the ethnically Swedish Sibelius would ultimately become the globally-recognized ambassador for Finnish music and the Finnish people’s quest for absolute cultural and political autonomy from czarist Russia. Like many Scandinavian musicians, Sibelius received a musical education that was strongly influenced by the Teutonic tradition of Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Schumann—a tradition in which the symphony was the principal mode of large-scaled orchestral expression.

Completed when the composer was thirty-three years old, the first of Sibelius’s seven symphonies was premièred by the Helsinki Philharmonic in 1899. Exhibiting the stark judgment of his own work later epitomized by his relative avoidance of composition during the final three decades of his life, Sibelius substantially revised the score after the first performance and may have destroyed the original manuscript, which has never resurfaced. His six subsequent works in the form would further develop Sibelius’s singular voice as a symphonist, but his inaugural effort established him as a peer of Bruckner and Brahms.

With a duration of 12:25, Nézet-Séguin’s traversal of the symphony’s opening movement is unusually expansive, but his pacing facilitates both exceptional clarity in the realizations of Sibelius’s orchestral textures and striking contrasts among the majestic fanfares for brass and percussion, the gossamer figurations for the strings and harp, the latter beautifully played by Danièle Habel, and the playful, almost rustic writing for the woodwinds. The plaintively meandering clarinet solo that introduces the Andante, ma non troppo passage is thoughtfully phrased by Orchestre Métropolitain’s principal clarinetist, Simon Aldrich, and his colleagues in all sections of the orchestra deliver their solos with unfluctuating musicality. The transition to the movement’s Allegro energico section is intelligently navigated by the conductor and zestfully executed by the orchestra.

An atmosphere of impending misfortune permeates the start of the Andante, ma non troppo lento movement, but, sensitive to the momentum generated by Sibelius’s thematic metamorphoses, Nézet-Séguin does not surrender to tragedy. Rather, he conjures a tonal environment in which moments of mystery are resolved by bursts of melody. His is a notably optimistic reading of the piece: whilst wholly respecting the fundamental structure of the movement, he emphasizes the expressive significance of the brightness that penetrates the music’s gloom, finding more excitement than angst in the agitation that propels the movement to its tranquil conclusion, which in this performance suggests a cathartic moment of relief after a grave emotional struggle.

In comparison with similar movements in the symphonies of other consequential contributors to the genre, Sibelius’s Allegro Scherzo is especially unconventional. This Scherzo is anything but the expected jocular episode: the disquiet of the preceding movement returns, only temporarily abated, infusing the music with an oppressive uncertainty. The orchestra’s opulent but astonishingly transparent sound potently imparts the distress that haunts the music, but here, too, Nézet-Séguin pursues a course that circumvents unequivocal desolation. His approach to this music is uncommonly attentive to the fact that, as surely in music as in nature, shadows cannot exist without light. The Orchestre Métropolitain’s playing echoes this conviction, lending the ambiguous stretto an undertone of hesitant contentment.

Marked ‘quasi una fantasia’ by Sibelius, the symphony’s Finale undulates from an initial Andante through a progression of tempi and temperaments that recapitulates the dramatic journey of the previous movements with ambivalence reminiscent of the final movements of Mahler’s symphonies. Nézet-Séguin’s management of the lyrical effusions spotlights the kinship between Sibelius’s and Tchaikovsky’s orchestral writing. In this performance, the brief but meaningful silences that punctuate the symphony’s last pages are staggeringly jarring. The conductor employs these abrupt interruptions in the narrative’s dénouement as opportunities for aural palate-cleansing, preparing the listener for the movement’s terminal trajectory. Even with the portentous din of the percussion, the symphony seems not to truly end but merely to stop. Instead of imposing a speculatory resolution upon the music, Nézet-Séguin leaves the impression of the symphony’s final movement being a flow of thought that exhausts and then pauses to replenish its musical resources.

Since Robert Kajanus, who conducted the first performance of Sibelius’s revision of the First Symphony in 1900, recorded the work with the London Symphony Orchestra in 1930, this score has presented listeners with difficult choices. This is a piece that affirms that the notion of any interpreter or performance being the ‘greatest of all time’ is as stupid in music as in sports. The composer having appreciated the young conductor’s earliest recordings of his music, Herbert von Karajan’s Deutsche Grammophon account of the First Symphony with the Berliner Philharmoniker has long enjoyed exalted status, but dozens of challengers have widened and complicated the symphony’s discography. It is fatuous to argue that this or any recording of Sibelius’s First Symphony is definitive, but this performance and its conductor wield greatness very persuasively.

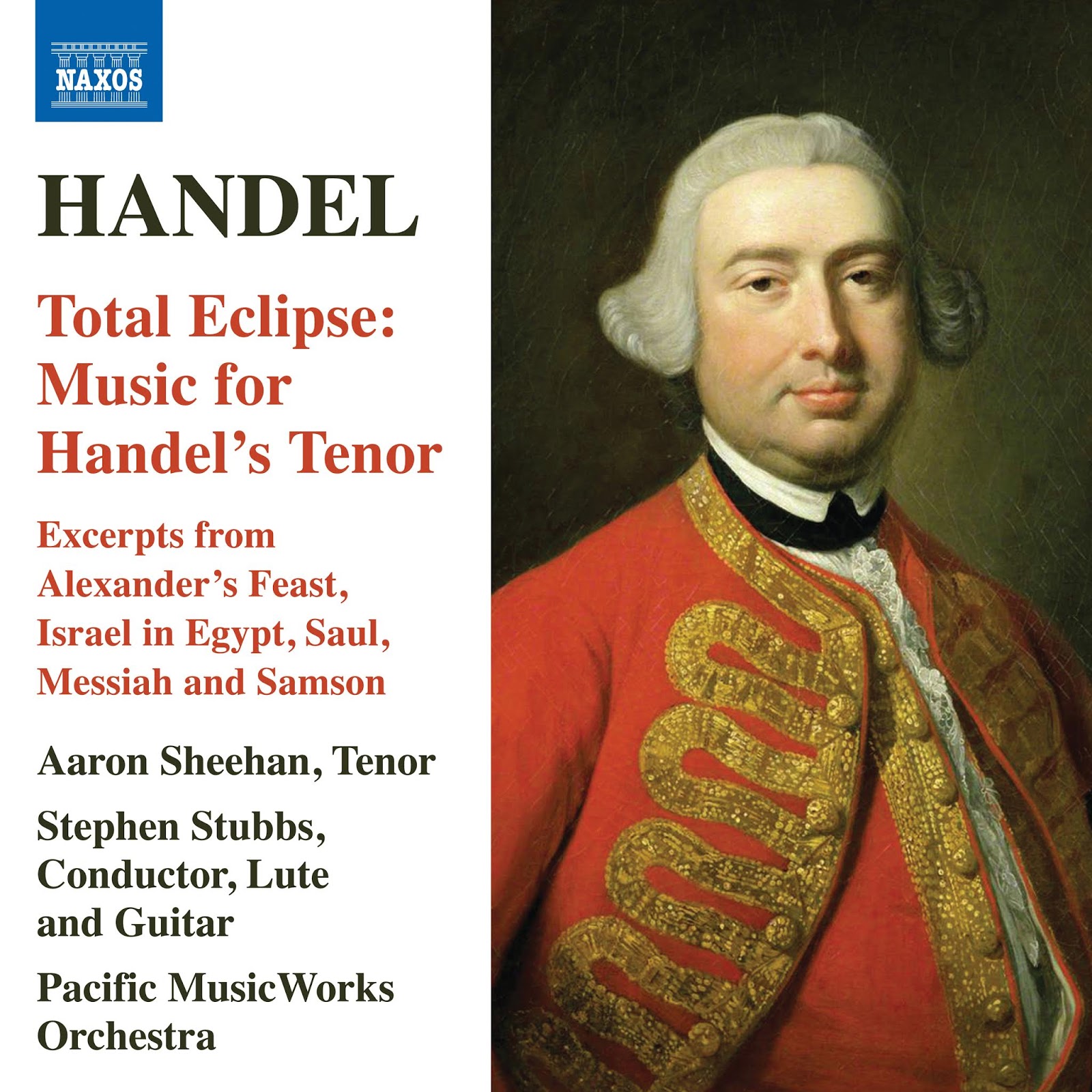

GEORG FRIEDRICH HÄNDEL (1685 – 1759): Total Eclipse: Music for Handel’s Tenor —

GEORG FRIEDRICH HÄNDEL (1685 – 1759): Total Eclipse: Music for Handel’s Tenor —