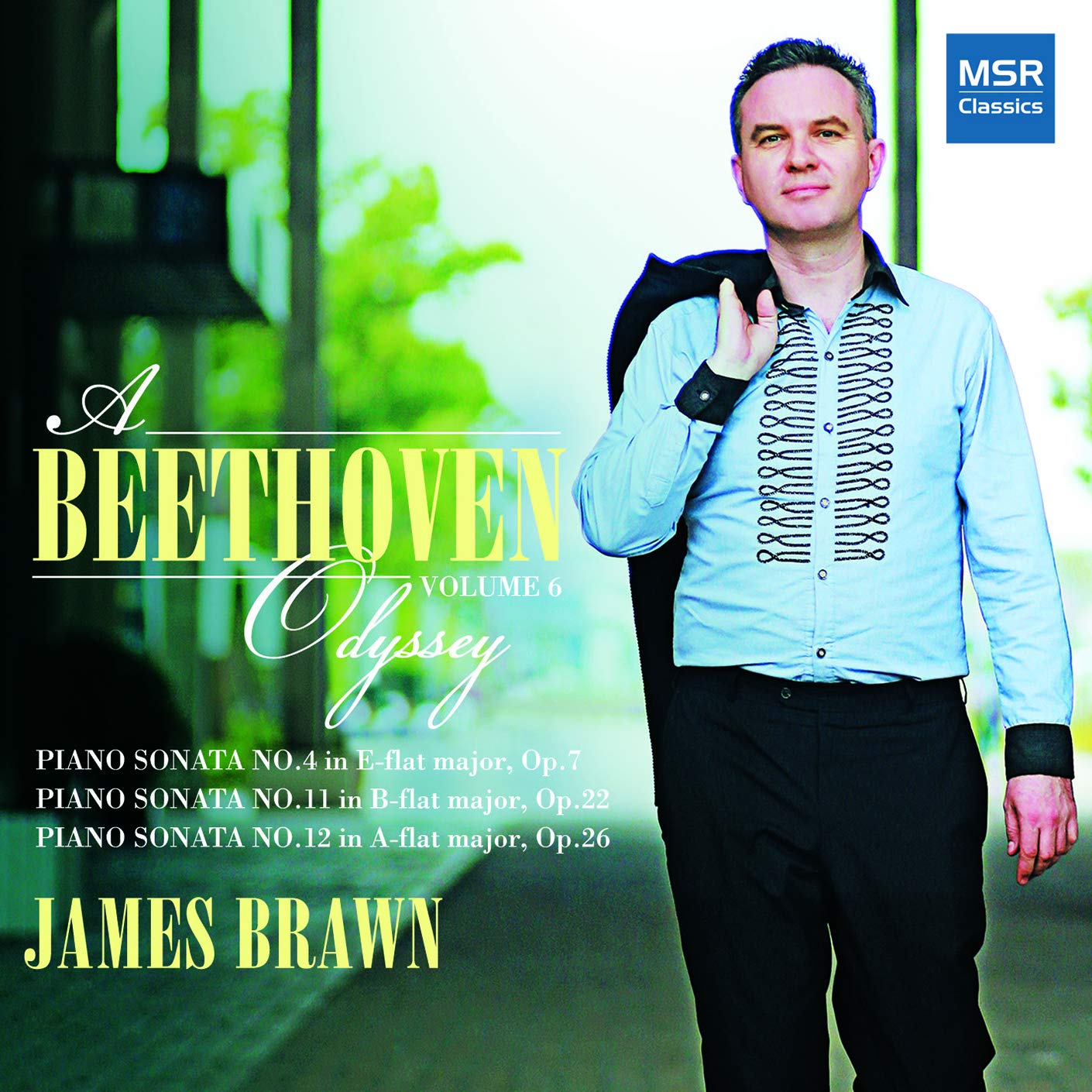

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770 – 1827): A Beethoven Odyssey, Volume Six – Piano Sonatas Nos. 4 in E♭ major (Opus 7), 11 in B♭ major (Opus 22), and 12 in A♭ major (Opus 26) — James Brawn, piano [Recorded in Potton Hall, Suffolk, UK, 16 – 18 December 2018; MSR Classics MS 1470; 1 CD, 73:43; Available from MSR Classics and major music retailers]

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770 – 1827): A Beethoven Odyssey, Volume Six – Piano Sonatas Nos. 4 in E♭ major (Opus 7), 11 in B♭ major (Opus 22), and 12 in A♭ major (Opus 26) — James Brawn, piano [Recorded in Potton Hall, Suffolk, UK, 16 – 18 December 2018; MSR Classics MS 1470; 1 CD, 73:43; Available from MSR Classics and major music retailers]

The world has changed immeasurably in the 192 years since Ludwig van Beethoven died on 26 March 1827. Were he walking along the streets of Vienna today, he would encounter familiar landmarks, some of them scarred by war, but the spaces and societies that have evolved beyond their façades would little resemble the imperial city that he knew. Only in the Wienerwald, where, like many residents of the Hapsburg capital, he sought refuge from the city’s tumult and found inspiration in unspoiled nature, would Beethoven now rediscover the sights and sounds that so indelibly impacted his work. The vistas of the musical metropolis from Kahlenberg’s summit are much different in 2019 from when Beethoven last viewed them, but, having persevered through nearly two centuries of alternating decadence and deprivation, Vienna retains much of the inimitable essence celebrated by artists as diverse as the city itself.

A similar phenomenon of familiar unfamiliarity can be observed in studying, performing, and recording Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas. Their genesis spanning nearly three decades, writing his thirty-two Piano Sonatas occupied Beethoven during a substantial portion of his compositional career, engendering a broad stylistic progress from Classicism learned from Haydn, Salieri, and Mozart to Romanticism prefiguring Schumann and Brahms. Attentive pianists and listeners can perceive in the early Sonatas fundamental modes of expression that Beethoven reworked and refined in his last efforts in the genre, in which a lifetime of challenging boundaries of form and technique begat formidable virtuosity. The stylistic innovations wrought by the composer in the Sonatas, more celebrated in the late scores but sometimes more conspicuous in earlier works, rival the most momentous advancements in Western culture, but, as pianist James Brawn’s Beethoven Odyssey on MSR Classics avers, recognition of the marvels of the individual Sonatas is enhanced when they are assessed cumulatively, via the work of a musician who fully comprehends and conveys each Sonata’s rightful place among its brethren.

In the Twenty-First Century, when commercial considerations rightly or wrongly seem more prominent than artistic merit in many deliberations concerning the recording of Classical Music, it is exceptionally rare for a pianist to have an opportunity to record a complete traversal of Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas—and still rarer for a pianist to genuinely deserve such an opportunity. Laments for the demise of the Classical recording industry having thankfully proved to have been premature, the new millennium has yielded a profusion of recordings, an unfortunate portion of which document performances that in years past would likely have been deemed unworthy of preservation. It is not without justification that some listeners whose acquaintances with Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas were fostered by revered recordings by pianists like Artur Schnabel and Wilhelm Kempff complain of a dearth of more recent performances that offer original, legitimate interpretive insights to supplement those exhibited by pianists of the past.

The Beethoven discography suffers from no shortage of idiosyncratic performances of the Piano Sonatas, but, like Schnabel, Kempff, and especially Emil Gilels, whose untimely death regrettably prevented completion of his masterful Beethoven cycle for Deutsche Grammophon, Brawn plays Beethoven Sonatas with imagination and individuality that never diminish the composer’s singular presence in the music. His previous recordings of Beethoven Sonatas evinced the efficacy of Brawn’s unmistakably intimate but commendably unaffected relationship with the music. Like Brawn’s playing of each Sonata, the present disc is both an extraordinary achievement in its own right and an aptly evocative, searching continuation of the pianist’s Beethoven Odyssey.

The sixth volume of A Beethoven Odyssey begins with a performance of Sonata No. 4 in E♭ major (Opus 7) in which both the exuberant youthfulness and the contrasting maturity of the music are intelligently accentuated. Written in November 1796 during a visit to Keglevičov palács in Bratislava, where he taught the dedicatee of Piano Sonata No. 7 and the contemporaneous Piano Concerto No. 1, Ana Luiza Barbara Keglević, the Opus 7 Sonata shares its key with some of Beethoven’s most overtly grandiose music, notably the Third Symphony and the Fifth Piano Concerto.

The composer himself christened Opus 7 as the ‘Grande Sonate’ upon its first publication in October 1797, and the expansive, unapologetically symphonic scale of the the opening Allegro molto e con brio movement here receives deft handling that fully meets the bravura and expressive demands of the music. Nevertheless, not even the most opulent passages draw from Brawn playing that overwhelms the music. In his performances of the three Sonatas on this disc, he never joins the ranks of pianists who succumb to the temptation to over-Romanticize these pieces. Instead, he demonstrates that, though Weber and Wagner are close on the horizon, not only Haydn and Mozart but also Bach and Händel meaningfully influenced the young Beethoven.

Unfailingly faithful to the composer’s instructions, Brawn responds to the ‘con gran espressione’ character of Opus 7’s Largo movement with poignant eloquence. His sapient phrasing, engagingly rhapsodic but allied with rhythmic tautness of almost mathematical precision, facilitates an organic focus on melody that lends his performance an engaging bel canto sensibility. The energetic Allegro is played with galvanizing momentum that transitions coherently to the Poco allegretto e grazioso pace of the closing Rondo. There is a suggestion in the Sonata’s final pages of the ambivalent playfulness found in Mahler’s music. Simultaneously conjuring the spirits of Prospero and Puck, Brawn effectuates an ideal balance between sun and shade—and, vitally, between past and future.

Dedicated to Fürst Lichnowsky, Kammerherr to the imperial court of Franz II, Sonata No. 12 in A♭ major (Opus 26) dates from the turn of the Nineteenth Century, when Beethoven was also completing his First Symphony. Stylistically ambitious, not least in each of the four movements being centered in the home key of A♭ major, the Opus 26 Sonata follows the example of Mozart’s K. 331 Sonata by abandoning an introduction in a fast tempo in favor of a slower movement with variations. In the performance on this disc, Brawn navigates each transformation of the principal subject in Beethoven’s ingeniously-crafted Andante con variazioni with cognizance of the way in which it propels the music’s emotional narrative.

The Sonata’s Allegro molto Scherzo and Trio are played with an appealing lightness, the difficulties of the writing conquered with palpable joy. Beethoven gave Opus 26’s third movement the title ‘Marcia funebre sulla morte d’un Eroe’ and created music that communicates feelings of tragic loss that are at once resoundingly universal and devastatingly personal. By allowing the listener to experience details of Beethoven’s writing rather than a pianist’s egotistical executions thereof, the restraint of Brawn’s performance heightens appreciation of the composer’s true intentions. In the Allegro, too, Brawn serves no master other than Beethoven. His delivery of fleet passagework is brilliant, but accurate playing of notes at a brisk speed is only a small part of his artistry. It may seem nonsensical to state that Brawn plays music, not notes, but listeners who have endured pedestrian performances by score-bound pianists can discern the difference.

When preparing his four-movement ‘Grand’ Sonatas for initial publication and when later contemplating his artistic legacy, Beethoven cited Sonata No. 11 in B♭ major (Opus 22) as his favorite among the early Sonatas. Hearing Brawn’s performance of the Sonata would likely have solidified his opinion. The unflinching boldness of the pianist’s approach to the daunting Allegro con brio emphasizes the depths of Beethoven’s exegesis of sonata form. The composer’s inquisitive dismantling, experimenting, and reassembling the sonata according to his own design pervades the movement’s exposition, and Brawn ensures that every bar of the music inhabits its proper place.

Bach, Händel, Mozart, Brahms, and Mahler wielded affinities for writing music that seems to halt the passage of time and dissect the beating hearts of human emotions, but Beethoven possessed a singular ability to imbue strikingly simple, sometimes banal melodies with tremendous expressive potency. That skill was deployed sublimely in the composition of Opus 22’s Adagio con molto espressione movement. A sibling of the slow movements in the Violin Concerto, the Fifth Piano Concerto, and the Ninth Symphony and the ‘Agnus Dei’ in the Missa solemnis, this music beguiles even in an indifferent performance. Brawn’s performance of it is a peer of Maria Callas’s singing of Amina’s ‘Ah! non credea mirarti’ in Bellini’s La sonnambula.

The ethos of the Minuetto and Minore of Opus 22 is nearer to that of a Mahler symphonic scherzo than to the formal minuets found in Haydn’s symphonies and chamber music, but, like his Bohemian contemporary Jan Václav Dusík, Beethoven integrated precepts gleaned from the work of his predecessors into his own ideas, producing music that anticipates the Nineteenth Century and recalls the Eighteenth but is unmistakably Beethoven’s work. The Sonata’s Allegretto Rondo also exemplifies the composer’s uncanny faculty for adapting the musical language of the past into his own unique dialect. Brawn’s fluency in the idiom affords uncommon clarity, his playing infusing rejuvenating transparency into music that is often muddled in overzealous performances. Fashioning his performance as a dialogue among the voices of the music’s subjects and countersubjects, Brawn presents Opus 22 not as an esoteric treatise but as a thriving musical organism.

In the first nineteen years of the Twenty-First Century, some musicians, musicologists, and music lovers have posited that the quality and importance of Beethoven’s music have been exaggerated. Admittedly, there have been performances of Beethoven’s music that support this assertion. In the course of James Brawn’s Beethoven Odyssey to date, the pianist’s astounding technical acumen has accomplished many wonders, one of the most exciting of which is the spontaneity that he imparts in impeccably-rehearsed performances. This is the crucial attribute that too many performances of Beethoven’s music lack. It is possible that the significance of Beethoven’s work has been unnecessarily aggrandized, but the value of A Beethoven Odyssey cannot be overstated. This sixth volume reminds the listener that, 192 years after Beethoven’s death, his music still surprises, stimulates, and satisfies, particularly when played as it is on this disc.

![ARTS IN ACTION: Soprano OTHALIE GRAHAM, Lady Macbeth in Opera Carolina's November 2019 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by the artist] ARTS IN ACTION: Soprano OTHALIE GRAHAM, Lady Macbeth in Opera Carolina's November 2019 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by the artist]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgWwyLpjrxjAZ3yfDSOzbkpNsnJOcGYjqzRbGTXp5ouuccK4f_OFAzVSaXQM5rJibgVmmSA2oSfNgapUd1bs76LzHsqltt0McbSiH0JEUqWEXgtLyd3joBnxOoUOLykSMtPOFqL_PcDHlw/s1600/Othalie-Graham.jpg) Lady of the hour: soprano Othalie Graham, Lady Macbeth in Opera Carolina’s November 2019 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth

Lady of the hour: soprano Othalie Graham, Lady Macbeth in Opera Carolina’s November 2019 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth![ARTS IN ACTION: mezzo-soprano GRACE BUMBRY as Lady Macbeth in Los Angeles Music Center Opera's 1987 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by Los Angeles Music Center Opera; image from the Detroit Public Library collection] ARTS IN ACTION: mezzo-soprano GRACE BUMBRY as Lady Macbeth in Los Angeles Music Center Opera's 1987 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by Los Angeles Music Center Opera; image from the Detroit Public Library collection]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiJNGH0jobw_tT-mFL_ExmRIawx7Z4WNW7sC6cXQXk5_Ul7g1kwoZNOp0lElsTUQsIl4G4Rc-c7lVoNQsd6brtq5EwnC5AK_B0UfjCFJxohzDjRJBPgobg8K2dhhSdLUykS0NiDT3aSFXM/s1600/Verdi_MACBETH_Grace-Bumbry_Los-Angeles-Music-Center-Opera_1987.jpg) La luce langue: mezzo-soprano Grace Bumbry as Lady Macbeth in Los Angeles Music Center Opera’s 1987 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth

La luce langue: mezzo-soprano Grace Bumbry as Lady Macbeth in Los Angeles Music Center Opera’s 1987 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth![ARTS IN ACTION: mezzo-soprano SHIRLEY VERRETT as Lady Macbeth (left) and baritone RYAN EDWARDS as Macbeth (right) in Boston Opera Company's 1976 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by Boston Opera Company] ARTS IN ACTION: mezzo-soprano SHIRLEY VERRETT as Lady Macbeth (left) and baritone RYAN EDWARDS as Macbeth (right) in Boston Opera Company's 1976 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by Boston Opera Company]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiGz-rBLRNbKeDIZLPN-3CtH8OI3mSaFI-6-QIpiFRmIM8X7T5rV8ruTu2bikXw5LUf3CIktbjuU2KI65uIJBxW2kKeEKb8pFOblRAJHSZni-83SxRXt_7sHdcZLX2s9feFhYUNb7GVlRM/s1600/Verdi_MACBETH_Shirley-Verrett_Ryan-Edwards_Boston-Opera_1976.jpg) Fatal mia donna: mezzo-soprano Shirley Verrett as Lady Macbeth (left) and baritone Ryan Edwards as Macbeth (right) in Boston Opera Company’s 1976 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth

Fatal mia donna: mezzo-soprano Shirley Verrett as Lady Macbeth (left) and baritone Ryan Edwards as Macbeth (right) in Boston Opera Company’s 1976 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth