On 7 September, the 2009 – 10 Royal Opera (Covent Garden) season will be launched with the first of two concert performances of Gaetano Donizetti’s rarely-performed opera semiseria Linda di Chamounix, seemingly absent from London stages since a 1963 performance at the St. Pancras Town Hall. Boasting an exciting cast including Cuban-American soprano Eglise Gutiérrez (in her Covent Garden début), Mariana Pizzolato, Ludovic Tézier, Alessandro Corbelli, and Luciano Botelho, conducted by Sir Mark Elder, the concerts will be recorded for commercial release by Opera Rara. Making his Royal Opera House début in the role of Carlo will be one of the finest young tenors presently before the public, Stephen Costello, 2009 recipient of the prestigious Richard Tucker Award.

On 7 September, the 2009 – 10 Royal Opera (Covent Garden) season will be launched with the first of two concert performances of Gaetano Donizetti’s rarely-performed opera semiseria Linda di Chamounix, seemingly absent from London stages since a 1963 performance at the St. Pancras Town Hall. Boasting an exciting cast including Cuban-American soprano Eglise Gutiérrez (in her Covent Garden début), Mariana Pizzolato, Ludovic Tézier, Alessandro Corbelli, and Luciano Botelho, conducted by Sir Mark Elder, the concerts will be recorded for commercial release by Opera Rara. Making his Royal Opera House début in the role of Carlo will be one of the finest young tenors presently before the public, Stephen Costello, 2009 recipient of the prestigious Richard Tucker Award.

A native of Philadelphia, Mr. Costello graduated in 2007 from that city’s renowned Academy of Vocal Arts after having already earned an incredible plethora of distinctions: First Prize in the 2006 George London Foundation for Singers Competition, First and Audience Prizes in the Giargiari Competition, and First Prize in the Licia Albanese Puccini Foundation Competition, in addition to the Academy of Vocal Arts’ Opera Club Award. Surely the most precious prize Mr. Costello earned during his studies at AVA is the hand of his beautiful wife, soprano Ailyn Pérez, with whom he frequently performs.

Prior even to his graduation from AVA, Mr. Costello achieved considerable successes within a six-month period in 2006 with his début in staged opera as Rodolfo in La Bohème at Fort Worth Opera and his European début at Opéra National de Bordeaux as Nemorino in L’Elisir d’Amore. Since that time, Mr. Costello’s repertory has expanded with critically-acclaimed performances of roles by Mozart, Donizetti, Verdi, Mascagni, and Puccini, and even the Steuermann in Wagner’s Der Fliegende Holländer (opposite the towering Holländer of James Morris).

Mr. Costello first captured the collective attention of the American opera-going public on 13 November 2005 at Carnegie Hall with his swaggering account of the Fisherman (who, in the spirit of the score, has his share of top C’s) in an Opera Orchestra of New York concert performance of Rossini’s sprawling Guillaume Tell. Critic Robert Levine wrote in a review of the performance on ClassicsToday.com that Mr. Costello ‘was graceful as a fisherman who sings a lovely serenade in the first act (with its own pair of high Cs!).’ The journey of one of American’s most beautiful voices was launched.

Among even the finest native-born American singers of previous generations, the road to the Metropolitan Opera almost invariably wound through dozens of smaller European houses and regional companies in North America. Instances such as that encountered on 6 December 1941, in which at short notice the young Astrid Varnay made her MET début as Sieglinde in a performance of Die Walküre opposite the Brünnhilde of Helen Traubel, are rare, a sort of cosmic alignment of destiny and necessity. Far more often, the young American singer’s entrance into the MET roster is less heralded, like that of James McCracken as Parpignol in the Company’s 21 November 1953 performance of La Bohème.

The MET’s 2007 – 2008 season began on 24 September 2007 with the premiere of Mary Zimmerman’s much-discussed new production of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. Singing the name-part for the first time at the MET was French coloratura soprano Natalie Dessay, whose flight from sanity was brought on by her slaying of Lucia’s arranged husband Arturo, sung by Mr. Costello in his MET début. Anthony Tommasini wrote in the 26 September edition of the New York Times that ‘an appealing young tenor, Stephen Costello, had a solid Met debut as the well-meaning Arturo.’ Writing on MusicalCriticism.com, John Woods expanded on Mr. Tommasini’s thoughts, noting that ‘a very strong impression was made by the young Stephen Costello as Arturo, which is no mean feat in such a small role.’ Freelance writers, bloggers, and listeners who heard the performance on the MET’s Sirius radio channel echoed this praise and took note of the MET début of an important artist.

Much as in the case of Astrid Varnay more than six decades earlier, destiny and necessity aligned on 25 October 2007, when neither of the tenors headlining the Zimmerman Lucia (Marcello Giordani and Giuseppe Filianoti) was contracted to sing his role. Young California-born tenor Todd Wilander made his MET début as Arturo, and Mr. Costello was promoted to the role of Edgardo. The evening’s performance was likewise broadcast over the MET’s Sirius radio channel, relaying into homes across America and throughout the world the emergence of a remarkable artist. Singing opposite the ethereally beautiful Lucia of the astonishingly gifted French soprano Annick Massis, an artist whose warmth of voice and personality created a Lucia very different from Natalie Dessay’s embodiment of the role, Mr. Costello rose magnificently to the challenge of singing such an important role at such a young age with America’s most significant opera company, sounding nowhere in the score finer than in Edgardo’s Tomb Scene at the end of the evening. From that evening, Mr. Costello’s career has spanned the globe in an array of electrifying performances in a myriad assortment of roles.

I recently had the great pleasure of speaking with Mr. Costello concerning the progress of his career to date, his musical interests and inspirations, and some of his future plans.

I recently had the great pleasure of speaking with Mr. Costello concerning the progress of his career to date, his musical interests and inspirations, and some of his future plans.

The first things that are apparent, both from hearing Mr. Costello sing and from speaking with him even briefly, are his genuine affection and enthusiasm for singing. The contrasting wit and humility with which he speaks of his approach to singing reveal not only an astute musical mind but also an unwavering commitment to the art of bel canto, whether in Donizetti, Verdi, or French repertory.

Perhaps it is cruel to suggest that many singers do not exhibit the same intelligence that Mr. Costello exudes in performance and in conversation. [How gladdened was the heart of this literary scholar to learn that Mr. Costello prepared for his performances as Cassio in Verdi’s Otello at Salzburg by re-reading Shakespeare’s play!] Jibes about cognitive disabilities among opera singers aside, Mr. Costello’s comments disclosed perhaps the most vital knowledge that should be possessed by any singer, that of the management of his own voice. The lure of Werther is powerful, for instance, but the title role is safely stored away for future consideration. Verdi’s Otello is regretfully conceded as an impossibility, even for some point on the distant horizon of Mr. Costello’s career. [This might seem an obvious distinction, but it eluded Luciano Pavarotti, whose voice was similar in size and reach to Mr. Costello’s: Pavarotti at least confined his attempts at Otello to concert performances.]

Fresh from having enjoyed great success in June as Rinuccio in Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi at the Festival dei due Mondi at Spoleto (Italy), Mr. Costello looks forward to reprising the role at Covent Garden in October, again opposite the Schicchi of Sir Thomas Allen, whom he describes as a ‘fantastic’ performer who brings great slyness and vigor to his interpretation of Schicchi. [An interview from Italian television in which Mr. Costello shares his insightful thoughts on the role of Rinuccio in Woody Allen’s production, seen at Spoleto, is posted at the end of this article.] Mr. Costello also spoke glowingly of a recent Ancona production of Rigoletto in which he was reunited with the ‘wonderful and kind’ Annick Massis, and of working with legendary (and legendarily divisive) conductor Riccardo Muti in the Salzburg production of Otello. ‘I wonder how he will be received at the MET,’ Mr. Costello said of Maestro Muti, who will conduct for the first time at the MET in February in a new production of Verdi’s Attila. ‘He is amazing.’

As he considers the next five years of his international career, bel canto continues to have a large presence in Mr. Costello’s diary, supplemented by later and contemporary repertory. He will return in March 2010 to Dallas Opera, scene of his triumphs as Leicester in Maria Stuarda and the title role Roberto Devereux, to sing Ishmael in the world premiere of Jake Heggie’s opera Moby Dick. He will take on the challenging role of Sir Riccardo Percy in another of Donizetti’s ‘British’ operas, Anna Bolena, to open the MET’s 2011 – 12 season (opposite, as it is rumored now, Anna Netrebko), following performances of the role in Dallas. Débuts are scheduled for San Francisco Opera, Glyndebourne Festival Opera, and the Wiener Staatsoper (in another of his fine bel canto portrayals, Nemorino in L’Elisir d’Amore). Mr. Costello remarked that singing bel canto ‘feels comforting for [his] voice.’ He continued by saying, ‘I wake up in the morning after singing bel canto and feel good.’ The seasons ahead offer many opportunities for good mornings.

A theme that I have often examined as both a writer and a musician is that of the solitude endured by the artist in the pursuit of his art. Viewing this as a matter of the proportions presented in Schubert’s Winterreise is perhaps to overinflate the significance of the issue, but every great artist makes sacrifices in order to give of himself. In many instances, these sacrifices are most poignantly felt in the inherent difficulties of forming, nurturing, and maintaining meaningful relationships when one or all parties are frequently away or mired in work. I was very touched in speaking with Mr. Costello by his comments regarding his wife. Their careers separate them for occasionally extensive periods of time: he is here and she is there, but they are nonetheless always with one another emotionally. Such support and contentment is at the heart of a truly sublime artistic partnership, and the happiness that results cannot fail to find voice in Mr. Costello’s singing.

The tradition of American singing that produced Eugene Conley and James McCracken, Jan Peerce and Richard Tucker, George Shirley and Vinson Cole is gloriously continued in Stephen Costello. Possessing a voice with a bright but plangent timbre, even throughout a considerable range that extends to a refulgent upper register, and laden with darker undertones, Mr. Costello already enjoys a career marked by accolades from both critics and audiences. With both a voice brimming with potential and genuine insightfulness to his credit, he is poised to be the leading tenor of his generation.

Sincerest thanks to Mr. Costello for his time, kindness, and candor.

Thanks also to Neil Funkhouser of Neil Funkhouser Artists Management, by whom Mr. Costello is managed. Click here to view Mr. Costello’s official profile on the website of Neil Funkhouser Artists Management.

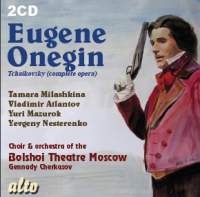

PYOTR ILYCH TCHAIKOVSKY / Пётр Ильи́ч Чайко́вский (1840 – 1893): Yevgeny Onegin / Евгений Онегин, Op. 24: Y. Mazurok (Yevgeny Onegin), T. Milashkina (Tatyana), V. Atlantov (Lensky), Y. Nesterenko (Gremin), T. Sinyavskaya (Olga), T. Tugarinova (Larina), L. Avdeeva (Filippyevna), L. Kuznetsov (Triquet), V. Yaroslavtsev (Zaretsky); Chorus and Orchestra of the Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow; Gennady Cherkasov [recorded in Radio Studio 5, Moscow, in 1984(?); alto 2007]

PYOTR ILYCH TCHAIKOVSKY / Пётр Ильи́ч Чайко́вский (1840 – 1893): Yevgeny Onegin / Евгений Онегин, Op. 24: Y. Mazurok (Yevgeny Onegin), T. Milashkina (Tatyana), V. Atlantov (Lensky), Y. Nesterenko (Gremin), T. Sinyavskaya (Olga), T. Tugarinova (Larina), L. Avdeeva (Filippyevna), L. Kuznetsov (Triquet), V. Yaroslavtsev (Zaretsky); Chorus and Orchestra of the Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow; Gennady Cherkasov [recorded in Radio Studio 5, Moscow, in 1984(?); alto 2007] f many sopranos born east of the Danube. Like her colleagues in this performance, Milashkina approaches her role honestly and with complete preparation. The tingling intensity of Yelena Kruglikova and the young Vishnevskaya is absent, but subtlety informs Milashkina’s singing throughout the performance. If Tatyana does not undergo in Milashkina’s hands either the sexual awakening depicted by Kruglikova or the intellectual transformation so vividly portrayed by Vishnevskaya, she is a less reticent girl from the start, a slight hint of slyness asserting itself in the more inward moments. Milashkina does not attempt to create a complicated psychological drama in the Letter Scene but instead focuses on observing all of Tchaikovsky’s instructions and loading the voice into her lines with precision. Here and elsewhere in her performance a tendency to deliver expansive lines as a series of individual phrases is bothersome, and there is a slightly pallid quality to the highest tones (though this may result as much or more from the engineering than from Milashkina’s vocal estate). What Milashkina offers is a Tatyana sung without gimmicks, a straightforward performance that holds few surprises but also few disappointments.

f many sopranos born east of the Danube. Like her colleagues in this performance, Milashkina approaches her role honestly and with complete preparation. The tingling intensity of Yelena Kruglikova and the young Vishnevskaya is absent, but subtlety informs Milashkina’s singing throughout the performance. If Tatyana does not undergo in Milashkina’s hands either the sexual awakening depicted by Kruglikova or the intellectual transformation so vividly portrayed by Vishnevskaya, she is a less reticent girl from the start, a slight hint of slyness asserting itself in the more inward moments. Milashkina does not attempt to create a complicated psychological drama in the Letter Scene but instead focuses on observing all of Tchaikovsky’s instructions and loading the voice into her lines with precision. Here and elsewhere in her performance a tendency to deliver expansive lines as a series of individual phrases is bothersome, and there is a slightly pallid quality to the highest tones (though this may result as much or more from the engineering than from Milashkina’s vocal estate). What Milashkina offers is a Tatyana sung without gimmicks, a straightforward performance that holds few surprises but also few disappointments. As even her most frenzied admirers accepted in the final years of the 1970’s that Birgit Nilsson’s dominance in the Hochdramatische repertory – especially Strauss’ Elektra and Färberin and Wagner’s Brünnhilde and Isolde – was drawing to its natural close, both opera lovers and the managers of the world’s opera houses searched the ranks of young singers for a suitable successor to Nilsson in German dramatic repertory. The protean vocal abilities of Nilsson seemed, and indeed have proved to be, not merely once-in-a-generation but once-in-a-century. Nonetheless, musical voices as significant as Elektra’s and Brünnhilde’s could not fall silent upon Nilsson’s retirement. During the last two decades of the twentieth century, there surely were respectable, idiomatic performances of German dramatic operas throughout the world, but among the heroines of those performances the undoubted mistress of the Hochdramatische repertory was Hildegard Behrens, who passed away unexpectedly in Tokyo on 18 August.

As even her most frenzied admirers accepted in the final years of the 1970’s that Birgit Nilsson’s dominance in the Hochdramatische repertory – especially Strauss’ Elektra and Färberin and Wagner’s Brünnhilde and Isolde – was drawing to its natural close, both opera lovers and the managers of the world’s opera houses searched the ranks of young singers for a suitable successor to Nilsson in German dramatic repertory. The protean vocal abilities of Nilsson seemed, and indeed have proved to be, not merely once-in-a-generation but once-in-a-century. Nonetheless, musical voices as significant as Elektra’s and Brünnhilde’s could not fall silent upon Nilsson’s retirement. During the last two decades of the twentieth century, there surely were respectable, idiomatic performances of German dramatic operas throughout the world, but among the heroines of those performances the undoubted mistress of the Hochdramatische repertory was Hildegard Behrens, who passed away unexpectedly in Tokyo on 18 August. bounded onto the stage in the second act, the very vocal and dramatic embodiment of the young, impetuous favorite daughter of a god. Few Brünnhildes have been more magisterial without being matronly in the Todesverkündigung, and few have expressed the girl’s heartbreak at being cast off by her father more pathetically or with greater sincerity. In Siegfried, it is virtually impossible to name a Brünnhilde, remembering even Florence Easton, who awakened to love with greater wonder and tonal beauty. Enduring what she perceives as shattering betrayal and sacrificing herself to union in death with her consort, Behrens’ Brünnhilde became in Götterdämmerung both the archetype and that thing she represents: the Eternal Feminine who offers herself as an instrument of redemption. Both Nilsson and Varnay sang the three Brünnhildes with greater vocal abandon (and, to be frank, more voice), but Behrens meaningfully personified the post-modern Brünnhilde, first and always a sensitive, emotionally intense woman.

bounded onto the stage in the second act, the very vocal and dramatic embodiment of the young, impetuous favorite daughter of a god. Few Brünnhildes have been more magisterial without being matronly in the Todesverkündigung, and few have expressed the girl’s heartbreak at being cast off by her father more pathetically or with greater sincerity. In Siegfried, it is virtually impossible to name a Brünnhilde, remembering even Florence Easton, who awakened to love with greater wonder and tonal beauty. Enduring what she perceives as shattering betrayal and sacrificing herself to union in death with her consort, Behrens’ Brünnhilde became in Götterdämmerung both the archetype and that thing she represents: the Eternal Feminine who offers herself as an instrument of redemption. Both Nilsson and Varnay sang the three Brünnhildes with greater vocal abandon (and, to be frank, more voice), but Behrens meaningfully personified the post-modern Brünnhilde, first and always a sensitive, emotionally intense woman.

Central to the repertory of every middling and greater opera house in the world, and especially to that of the Arena di Verona, Aida is one of the pillars upon which Verdi’s legacy rests and has proved perennially popular with audiences since its first performance in Cairo on 24 December 1871. The principal roles – Aida, Amneris, Radamès, and Amonasro – have attracted all the greatest singers with voices to do them justice (and more than a few who lacked appropriate voices), and Ramfis and the King are gift-roles for basses young and old.

Central to the repertory of every middling and greater opera house in the world, and especially to that of the Arena di Verona, Aida is one of the pillars upon which Verdi’s legacy rests and has proved perennially popular with audiences since its first performance in Cairo on 24 December 1871. The principal roles – Aida, Amneris, Radamès, and Amonasro – have attracted all the greatest singers with voices to do them justice (and more than a few who lacked appropriate voices), and Ramfis and the King are gift-roles for basses young and old. even Franco Corelli sang Radamès with the dash and abandon del Monaco displays in this performance. There is stiffness in ‘Celeste Aida,’ but Verdi must surely accept some responsibility for that: the placement of a character’s only aria ( and, at that, one of the most famous arias in Italian opera) within moments of his first entrance has earned the composer countless curses from tenors. The hurdle of the aria successfully cleared, del Monaco settles into a trajectory of increasing dramatic intensity as he encounters first Amneris, then Aida, and finally Amonasro. In the final Tomb Scene it is possible to long for a somewhat less full-throated approach, but del Monaco avoids the roaring heard from some tenors – and also the falsetto purring of some tenors determined to ‘go gentle into that good night.’ In Radamès final-act encounter with Amneris, del Monaco’s singing exudes precisely the sort of clenched-fists, masculine exasperation demanded by the music. Though in a general sense this is not del Monaco at his best, this is unquestionably a very fine performance of Radamès.

even Franco Corelli sang Radamès with the dash and abandon del Monaco displays in this performance. There is stiffness in ‘Celeste Aida,’ but Verdi must surely accept some responsibility for that: the placement of a character’s only aria ( and, at that, one of the most famous arias in Italian opera) within moments of his first entrance has earned the composer countless curses from tenors. The hurdle of the aria successfully cleared, del Monaco settles into a trajectory of increasing dramatic intensity as he encounters first Amneris, then Aida, and finally Amonasro. In the final Tomb Scene it is possible to long for a somewhat less full-throated approach, but del Monaco avoids the roaring heard from some tenors – and also the falsetto purring of some tenors determined to ‘go gentle into that good night.’ In Radamès final-act encounter with Amneris, del Monaco’s singing exudes precisely the sort of clenched-fists, masculine exasperation demanded by the music. Though in a general sense this is not del Monaco at his best, this is unquestionably a very fine performance of Radamès. Even baritones who are greater ‘artists’ than Protti often portray Amonasro as a frustratingly one-dimensional figure, with either tenderness or menace to the fore. In Protti’s performance, Amonasro is both a loving father, the moments of paternal concern for Aida being very beautifully done, and a fiercely proud king determined to have bloody revenge. Rarely among performances of the role, Amonasro’s moments of dramatic stress do not equate in Protti’s performance to stretches of vocal stress: Protti has the measure of the part within his grasp and is never caught out scrambling for notes or clutching at cheap effects. The formidable arcs of the Nile Scene are spanned with barrel-chested ease, and the gloating victor who ensnares Radamès in his treasonous trap is genuinely frightening without resorting to snarling or ugly tone. Those interested in operatic esoterica are fond of stating that this or that overlooked, underappreciated, or forgotten singer would be a great star were he or she singing now. To make such a statement about Protti would trivialize the success and significance of his four-decade career, but hearing this Amonasro gives cause to re-examine Protti’s work.

Even baritones who are greater ‘artists’ than Protti often portray Amonasro as a frustratingly one-dimensional figure, with either tenderness or menace to the fore. In Protti’s performance, Amonasro is both a loving father, the moments of paternal concern for Aida being very beautifully done, and a fiercely proud king determined to have bloody revenge. Rarely among performances of the role, Amonasro’s moments of dramatic stress do not equate in Protti’s performance to stretches of vocal stress: Protti has the measure of the part within his grasp and is never caught out scrambling for notes or clutching at cheap effects. The formidable arcs of the Nile Scene are spanned with barrel-chested ease, and the gloating victor who ensnares Radamès in his treasonous trap is genuinely frightening without resorting to snarling or ugly tone. Those interested in operatic esoterica are fond of stating that this or that overlooked, underappreciated, or forgotten singer would be a great star were he or she singing now. To make such a statement about Protti would trivialize the success and significance of his four-decade career, but hearing this Amonasro gives cause to re-examine Protti’s work. ed daughter of Pharaoh and the vulnerability of a woman very much in love. Power is the means by which Simionato’s Amneris reacts to her thwarted affections rather than the target at which she aims: this Amneris is a lioness thirsty for blood, but her rage is born of a perilously deep wound made palpable to the listener by Simionato’s singing in the final act. In the crucial Judgment Scene, Simionato rises to tragic grandeur by singing with anguished poise, the voice very beautiful despite the intensity of the music. It is easy to sense beneath the evenness of Simionato’s singing the heart of Amneris beating wildly, her emotions collapsing on themselves as she perceives the inevitability of Radamès’ condemnation. The full weight of the woman whose lover must go to his death crashes down on Amneris at once, and in Simionato’s performance the listener too endures this agony. Thrilling and moving in equal measures, Simionato’s performance is a remarkable example of the artistry of one of the twentieth century’s finest singers and an Amneris that rewards Verdi’s faith in the impact of the role.

ed daughter of Pharaoh and the vulnerability of a woman very much in love. Power is the means by which Simionato’s Amneris reacts to her thwarted affections rather than the target at which she aims: this Amneris is a lioness thirsty for blood, but her rage is born of a perilously deep wound made palpable to the listener by Simionato’s singing in the final act. In the crucial Judgment Scene, Simionato rises to tragic grandeur by singing with anguished poise, the voice very beautiful despite the intensity of the music. It is easy to sense beneath the evenness of Simionato’s singing the heart of Amneris beating wildly, her emotions collapsing on themselves as she perceives the inevitability of Radamès’ condemnation. The full weight of the woman whose lover must go to his death crashes down on Amneris at once, and in Simionato’s performance the listener too endures this agony. Thrilling and moving in equal measures, Simionato’s performance is a remarkable example of the artistry of one of the twentieth century’s finest singers and an Amneris that rewards Verdi’s faith in the impact of the role. bel canto roles such as Elvira in Bellini’s Puritani and Verdi’s Gilda. As captured by studio microphones, the voice seems expansive but not particularly large, with a slightly fluttery vibrato that brings to mind several famous Spanish singers. NHK’s microphones reveal the full richness and vibrancy of Tucci’s voice, however, the security of her tone and technique expanding into every bar of Aida’s music. Simply put, Tucci is a magnificent – and, for me, revelatory – Aida. From her first entrance, Tucci’s Aida displays the same ambiguity Simionato brought to Amneris, both a royal personage and a woman wholly in the throes of love. Vocally, the accuracy and attractiveness of Tucci’s singing are astonishing considering the circumstances of a staged performance. Dramatically, Tucci suffers nothing from comparisons with her more famous rivals and improves upon the work of most of them owing simply to her innate understanding of the organic progressions of the vocal lines and idiomatic sincerity. This is an Aida who wears her heart on her sleeve, so to speak, without condescending to the notion of expressing the most delicate emotions in music of grand proportions. As such, Tucci proves the rare Aida who completely earns the distinction of being the opera’s name-part, a woman who is the center of the drama rather than a guileless victim of it. Tucci’s Aida is a performance that cannot have been oft equaled before or since.

bel canto roles such as Elvira in Bellini’s Puritani and Verdi’s Gilda. As captured by studio microphones, the voice seems expansive but not particularly large, with a slightly fluttery vibrato that brings to mind several famous Spanish singers. NHK’s microphones reveal the full richness and vibrancy of Tucci’s voice, however, the security of her tone and technique expanding into every bar of Aida’s music. Simply put, Tucci is a magnificent – and, for me, revelatory – Aida. From her first entrance, Tucci’s Aida displays the same ambiguity Simionato brought to Amneris, both a royal personage and a woman wholly in the throes of love. Vocally, the accuracy and attractiveness of Tucci’s singing are astonishing considering the circumstances of a staged performance. Dramatically, Tucci suffers nothing from comparisons with her more famous rivals and improves upon the work of most of them owing simply to her innate understanding of the organic progressions of the vocal lines and idiomatic sincerity. This is an Aida who wears her heart on her sleeve, so to speak, without condescending to the notion of expressing the most delicate emotions in music of grand proportions. As such, Tucci proves the rare Aida who completely earns the distinction of being the opera’s name-part, a woman who is the center of the drama rather than a guileless victim of it. Tucci’s Aida is a performance that cannot have been oft equaled before or since.