WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756 – 1791): La clemenza di Tito, K. 621—Rolando Villazón (Tito Vespasiano), Joyce DiDonato (Sesto), Marina Rebeka (Vitellia), Regula Mühlemann (Servilia), Tara Erraught (Annio), Adam Plachetka (Publio); RIAS Kammerchor, Chamber Orchestra of Europe; Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conductor [Recorded during concert performances in Festspielhaus Baden-Baden, Baden-Baden, Germany, in July 2017; Deutsche Grammophon 483 5210; 2 CDs, 140:36; Available from Amazon (USA), fnac (France), iTunes, jpc (Germany), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756 – 1791): La clemenza di Tito, K. 621—Rolando Villazón (Tito Vespasiano), Joyce DiDonato (Sesto), Marina Rebeka (Vitellia), Regula Mühlemann (Servilia), Tara Erraught (Annio), Adam Plachetka (Publio); RIAS Kammerchor, Chamber Orchestra of Europe; Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conductor [Recorded during concert performances in Festspielhaus Baden-Baden, Baden-Baden, Germany, in July 2017; Deutsche Grammophon 483 5210; 2 CDs, 140:36; Available from Amazon (USA), fnac (France), iTunes, jpc (Germany), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

1791 was a remarkable year for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. After celebrating his thirty-fifth birthday in January, he produced three of his most enduring and influential compositions: the E♭-major String Quintet (K. 614), the Clarinet Concert (K. 622), and his opera Die Zauberflöte. In July, he and his wife welcomed the second of their children who would eventually reach adulthood, their son Franz Xaver Wolfgang. Sadly, the infant would need to survive only a few months in order to outlive his father. When Mozart died on 5 December 1791, the works dating from his final year, including the unfinished Requiem and the motet ‘Ave verum corpus,’ essentially became characters in a drama that grew ever more fantastical until the Mozart known to the musical denizens of Enlightenment Vienna was little more than a shadow in his own spectacle.

Until the second half of the Twentieth Century, a little-read chapter in the story of the last months of Mozart’s life recounted the genesis of La clemenza di Tito, an opera seria of the type that was a relic of earlier generations, though still a respected and in some circles, like that of which Mozart’s supporter Gottfried van Swieten was the center, beloved one. The death of the Hapsburg emperor Joseph II in February 1790 closed Vienna’s theatres whilst Mozart was at the zenith of his faculties, but the ascension of Joseph’s brother Leopold II to the throne made amends with an opportunity to write an opera to celebrate the new monarch’s coronation as King of Bohemia. The contract for arranging the composition and performance of the opera was granted to Prague impresario Domenico Guardasoni, whose invitation to participate in the project was declined by Antonio Salieri. The tremendous success of the inaugural production of Don Giovanni, staged in Prague in October 1787, made Mozart a viable candidate to substitute for Salieri, and, despite being immersed in the preparation of Die Zauberflöte, the younger composer accepted the offer and started his work—and how he worked! Less than two months separated Guardasoni’s receipt of the contract on 8 July and the world première of La clemenza di Tito in Prague’s Stavovské divadlo on 6 September.

Unlike many composers of his time, Mozart prized novelty in his writing for the stage, preferring to work with libretti prepared specially for him rather than perpetuating the tradition of using widely-traveled texts already employed by other composers. In this regard, La clemenza di Tito is an anomaly among Mozart’s mature operas, its libretto, an adaptation by Caterino Mazzolà of the work of the Eighteenth Century’s busiest librettist, Pietro Metastasio, having been previously set by nearly forty other composers including Antonio Caldara (1734), Christoph Willibald Gluck (1752). and Baldassare Galuppi (1759). For Prague, Mazzolà substantially streamlined and restructured the drama, reducing Metastasio’s three acts to two and eliminating many arias, only a few of which were replaced with new texts. In truth, the original goal of the commission was to serenade Leopold II with a wholly-new piece, but the writing of a fresh libretto would have left even less time for composition of the music. Nevertheless, the recycled tale of amorous intrigue, political upheaval, and royal magnanimity clearly inspired Mozart, who had fallen ill by the time that the opera reached the stage. His burden was lightened by the task of writing secco recitative being placed in other hands, but it is doubtful that, facing the pressure of such a deadline, the industrious Rossini or Donizetti could have crafted a score of the quality and significance of La clemenza di Tito under similar circumstances.

Expanding the cycle populated to date by recordings of Die Entführung aus dem Serail and Mozart’s three operas with libretti by Lorenzo da Ponte and to be joined in due course by a souvenir of this month’s Festspielhaus Baden-Baden concert performances of Die Zauberflöte, this Clemenza di Tito deepens Québécois conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s experience with the music of a composer in whose musical language he has demonstrated a notable fluency. It is hardly surprising that this young conductor, still only in his early forties, excels at leading performances of scores shaped by white-hot passions, but his fervent handling of the ‘formal’ style of La clemenza di Tito is tempered by commendable and period-appropriate restraint. The contrasts among fast and slow sections of arias are sometimes slightly exaggerated, but the opera’s emotional transitions benefit tremendously from the heightened sense of impending calamity that this engenders. On the whole, Nézet-Séguin’s tempi are both prudent and sensitive: the quickest passages are controlled, and slower music rarely languishes.

The conductor’s concerted efforts to keep the drama moving at a sensible, sustainable pace are supported by Jory Vinikour’s fortepiano continuo, played with technical and intellectual nimbleness, and expertly seconded in secco recitative by cellist William Conway. Likewise, the Chamber Orchestra of Europe musicians deliver performances that spur renewed admiration of Mozart’s skill as an orchestrator, not least in the brilliant—and, in this performance, brilliantly-played—Overture and the delightfully martial Maestoso Marcia in Act One. Some performances of La clemenza di Tito create the illusion that in this score Mozart’s creative genius took a step back from his achievements in the da Ponte operas and Die Zauberflöte, first performed in Vienna three weeks after Tito’s Prague première, but the performance incited by Nézet-Séguin corroborates the assertion that La clemenza di Tito is a by no means unworthy sibling of Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte, and Die Zauberflöte.

Mozart’s operatic choral writing reached its apotheosis in La clemenza di Tito and Die Zauberflöte. In these works, the choristers genuinely participate in the drama rather than merely commenting on it. As the populace of Tito’s Rome, patricians and plebeians, the expert RIAS Kammerchor singers perform Mozart’s music with a balance of zeal and precision that complements Nézet-Séguin’s approach to the score. In Act One, they deliver ‘Serbate, o Dei custodi della Romana sorte’ with credible avidity, their plea for divine protection propelled heavenward on a torrent of accurately-pitched, perfectly-blended tone. The tumultuous music of the Act One finale could hardly be more different, and the mettle of their singing makes the fear and panic of the scene palpable. ‘Ah, grazie si rendano al sommo fattor’ in Act Two returns to a reverential manner, and the ensemble’s performance adapts accordingly. They preface the opera’s finale with a heartfelt account of ‘Che del ciel, che degli Dei tu il pensier,’ and their singing intensifies the catharsis of the final scene. Like Nézet-Séguin’s conducting, RIAS Kammerchor’s singing further spotlights the ingenuity that Mozart expended in the composition of La clemenza di Tito.

It is unusual to hear a singer of Czech bass-baritone Adam Plachetka’s abilities as Publio, the commander of Tito’s Praetorian guards, but the power of his singing gives the character a stronger presence than he typically commands. In the first of his trios, the ensemble with Vitellia and Annio in Act One, Plachetka is a rare Publio who is always noticeable. This is also true in the quintet, in which the bass-baritone voices Publio’s lines sonorously and energetically. Trios in Act Two unite him first with Vitellia and Sesto and then with Sesto and Tito: Plachetka makes a robust impression in both settings. Between these trios comes Publio’s aria, ‘Tardi s’avvede d’un tradimento,’ sung here with secure tone and solid technique. Plachetka’s voice remains audible and attractive in the opera’s closing ensemble, and his Publio sets a high standard both for his colleagues and for the performance of this rôle.

Irish mezzo-soprano Tara Erraught characterizes the young Annio with keenly-honed histrionic instincts and vocal technique that maintains the requisite style without sacrificing the emotive spontaneity of her singing. In the beautiful Andante duet with Sesto in Act One, ‘Deh, prendi un dolce amplesso,’ Erraught voices Annio’s words with obvious understanding of their meaning, and, here and in the subsequent duet with Servilia, ‘Ah, perdona al primo affetto,’ the mezzo-soprano imbues the rôle with significantly greater dramatic involvement than he wields in many performances. Like Plachetka’s Publio, Erraught’s Annio is engagingly conspicuous in both their trio with Vitellia and the momentous quintet that ends Act One.

The first of Annio’s arias in Act Two, the Allegretto ‘Torna di Tito a lato,’ is affectionately sung, but it is in the Andante aria ‘Tu fosti tradito’ that Erraught claims for herself a place alongside Brigitte Fassbaender and Frederica von Stade among the finest recorded interpreters of Annio. The appeal of her vocalism is consistent throughout the performance, but the parlous position in which Annio finds himself in ‘Tu fosti tradito,’ acknowledging that his friend Sesto’s deeds warrant a death sentence but entreating Tito to allow his deliberations to be guided by the mandates of his heart rather than the rule of law, inspirit Erraught’s depiction. In the opera’s finale, her Annio evinces the jubilation of having facilitated Sesto’s deliverance from an inglorious fate, and the magnetism of Erraught’s singing compels the listener to rejoice, as well.

In recent seasons, Swiss soprano Regula Mühlemann has rapidly established herself as one of her generation’s preeminent Mozart singers. Heard as Barbarina in Nézet-Séguin’s recording of Le nozze di Figaro and donning Papagena’s musical plumage in his Die Zauberflöte, she portrays Servilia in this performance of La clemenza di Tito with unforced charm and secure, often radiant singing. She does not over-accentuate the top As in the Act One duet with Annio, ‘Ah, perdona al primo affetto,’ instead emphasizing continuity of the musical line. She, too, utters her lines in the quintet with urgency and impeccable musicality. Mühlemann phrases Servilia’s Act Two aria in minuet time, ‘S’altro che lacrime per lui non tenti,’ liltingly, rising to a dulcet top A. Her tones gleam in the final scene, in which she resolves Servilia’s part in the drama with noteworthy comprehension of the intricacies of Mozart’s part writing.

That Latvian soprano Marina Rebeka’s repertoire has expanded in the past two years to include the title rôles in Bellini’s Norma, Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda, and Verdi’s Giovanna d’Arco and Luisa Miller is indicative of this artist’s musical intrepidity. It is also evidence of her technical fortitude. With Vitellia in La clemenza di Tito, Mozart created a full-blooded sister for Elettra in Idomeneo, re di Creta and Die Königin der Nacht in Die Zauberflöte—and, though he did not know it, a fantastic part for Marina Rebeka. Vitellia’s duet with Sesto in Act One, ‘Come ti piace, imponi,’ offers the soprano an opportunity to exhibit her talents, and she seizes it with alacrity, bringing mellifluous sounds to the Andante and projecting resonant top notes in the Allegro section. She quarries the rich lode of expressivity in the shift from Larghetto to Allegro in the aria ‘Deh, se piacer mi vuoi,’ executing the fiorature unflinchingly. Rebeka takes control of the trio with Annio and Publio with the authority of an emperor’s daughter, hurling out ‘Vengo! aspettate!’ with vehemence echoed by her effortless top B and thrilling launch to the infamous D6. As Vitellia’s plans spiral out of control in the final pages of Act One, Rebeka’s voice simmers with the heat of the flames that engulf the Campidoglio.

The Act Two trio with Sesto and Publio discloses a different dimension of Vitellia’s personality, and Rebeka voices her music with assurance. Words and notes erupt with the cataclysmic kinesis of Vesuvio in the accompagnato ‘Ecco il punto, o Vitellia,’ declaimed in this performance with Shakespearean perceptiveness. The plummets below the stave in the rondò aria ‘Non più di fiori vaghe catene’ are not easy going for Rebeka, but she shirks nothing, bravely traversing the two-octave interval to top A♭. As her quest for vengeance unravels and she confesses her treachery to the emperor, Vitellia leaves the world of Elettra and Die Königin der Nacht and enters the realm of Pamina, made worthy of mercy by tasting the bitter elixir of tragedy. The beauty of Rebeka’s singing makes this transformation especially apparent. Musically and dramatically, few singers manage to embody a character as completely as Rebeka animates Vitellia on this recording. Neither victim nor vixen, this Vitellia is merely, movingly human.

Among the many sparkling facets of Joyce DiDonato’s artistry, her singing of Mozart repertoire perhaps does not receive the attention that her performances of Baroque, bel canto, and contemporary music justifiably garner. This is an inexplicable injustice, as her depiction of Sesto in this recording of La clemenza di Tito is a performance of the sort of psychological depth and technical confidence that only a truly great singer can muster. In the past few seasons, the mezzo-soprano has sometimes discernibly worked harder to conjure the musical magic for which she is renowned, but her Sesto is a reminder of the wisdom of singers like Kirsten Flagstad and Birgit Nilsson, mistresses of other repertoire who insisted that periodically singing Mozart rôles is a soothing balm for the voice. Sesto’s music is daunting, but Mozart was too shrewd to write vocal lines that could not be sung.

After hearing DiDonato’s singing in the Act One Andante duet with Vitellia, ‘Come ti piace, imponi,’ doubting the veracity of Flagstad’s and Nilsson’s suggestion is unfathomable. Here and in the duet with Annio, ‘Deh, prendi un dolce amplesso,’ DiDonato’s vocalism is youthful, poised, and sincere: what artifice there is exists in the music. Weaving her voice into the colorful tapestry fabricated by Romain Guyot’s wonderful playing of the aria’s clarinet obbligato [his performance of the basset-horn obbligato in Vitellia’s rondò is equally superb], she delivers an astounding account of ‘Parto, parto, ma tu, ben mio,’ the crispness of her trills matched by the fluidity of her articulation of the triplet fiorature cresting on top B♭s in the fast-paced Allegro assai. Then, as Sesto wrests with his promise to slay Tito, she summons the potency of Greek tragedy in the accompagnato ‘O Dei! che smania è questa, che tumulto ho nel cor!’ The passage beginning with ‘Deh, conservate, o Dei, a Roma il suo splendor’ in the quintet is voiced with acute understanding of Sesto’s motivations and the conflicting loyalties that torment him.

Responding to Rebeka’s and Plachetka’s vocal sparks, DiDonato sings ‘Se al volto mai ti senti lieve aura che s’aggiri’ in the Act Two trio with Vitellia and Publio with imaginative nuance, followed by a subtle but steadfast reading of ‘Quello di Tito è il volto!’ in the subsequent trio with Tito and Publio. DiDonato’s performance of the Adagio rondò ‘Deh, per questo istante solo ti ricorda il primo amor’ affirms that this piece is in no way inferior to Sesto’s more famous aria in Act One. Interpreted by this singer, Sesto’s shame and self-loathing are uncommonly believable, not least when he declares ‘Tu, è ver, m’assolvi, Augusto, ma non m’assolve il core.’ There have been excellent recorded performances of Sesto’s music, foremost among which are Teresa Berganza’s portrayals for István Kertész and Karl Böhm, but DiDonato initiates a class of her own. So apt are her discreet embellishments that Mozart might have been whispering them in her ear. Her Donna Elvira in Nézet-Séguin’s Don Giovanni was a tremendous accomplishment, but this Sesto surpasses even her own best work.

In the first legs of Nézet-Séguin’s DGG Mozart journey, Mexican tenor Rolando Villazón surprised many listeners who questioned the wisdom of his Mozartian forays with vibrant, mostly stylish performances as Belmonte in Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Don Curzio in Le nozze di Figaro, Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni, and Ferrando in Così fan tutte. [Villazón’s rôle in the forthcoming Die Zauberflöte is Papageno.] Here mounting the imperial throne as the troubled but ultimately level-headed Tito Vespasiano, he does not fully rise to the level of those previous impersonations, but this is music in which many valiant efforts have fallen short of success. A cinematic stereotype of Roman emperors—either exasperatingly haughty or vulgarly libidinous and unfailingly speaking with a pompous British accent—persists in today’s cultural consciousness, and Villazón turns this paradigm on its head. His is a Tito more likely to be found among his subjects, devouring the marvels of Rome, than cloistered behind palace walls. He sculpts the lines of the Andante con moto aria ‘Del più sublime soglio l’unico frutto è questo’ with the steady hand of a master craftsman, little bothered by the frequent treks to G at the top of the stave. The reliability of the tenor’s G4 is further tested in Tito’s Allegro aria ‘Ah, se fosse intorno al trono,’ and Villazón again passes without cheating, laudably confronting every difficulty with determination.

There is an aura of a celebrant’s interactions with his congregation in Villazón’s singing of Tito’s Act Two scene with the chorus, his pronouncement of ‘Ah no, sventurato non sono cotanto’ ringingly regal in tone. His smoky timbre enables a probing explication of the emperor’s predicament in the accompagnato ‘Che orror! che tradimento!’ Villazón’s bold but calm demeanor is touchingly effective in this music and in the trio with Sesto and Publio. The aria ‘Se all’impero, amici Dei!’ is a veritable obstacle course, the tranquil contemplation of its Andantino section disrupted by a return to the galloping Allegro. When a singer as stylistically deft as Nicolai Gedda was unable to negotiate the aria’s dizzying fiorature cleanly under studio conditions, Villazón earns leniency, but no apology needs to be made for his performance. The pitches are there, and the top B♭s present no problems. The accompagnato ‘Ma che giorno è mai questo?’ is ideal territory for him, and he enlivens music in which leaner voices can sound feeble. Villazón’s voicing of ‘Il vero pentimento di cui tu sei capace’ in the finale scene proclaims that this Tito’s mild manner is a manifestation of courage, not weakness. Musically, this is not a flawless performance, but it is as thoughtful and enjoyable a portrayal of Tito as has been recorded.

Mozart’s correspondence divulges a fascinating profundity of self-awareness, but it is impossible to know whether the composer was cognizant as he left Prague after the première of La clemenza di Tito to return to Vienna and resume work on Die Zauberflöte that he had said his farewell to Italian opera. As is the case with Pergolesi, Schubert, Bellini, Mendelssohn, Chopin, and other composers who died young, later generations of musicians, listeners, and scholars ponder what these artists might have achieved had they lived longer. Many long-lived composers would undoubtedly savor a final effort in any genre as inventive as La clemenza di Tito and a performance of it as superlative as this one via which to be remembered.

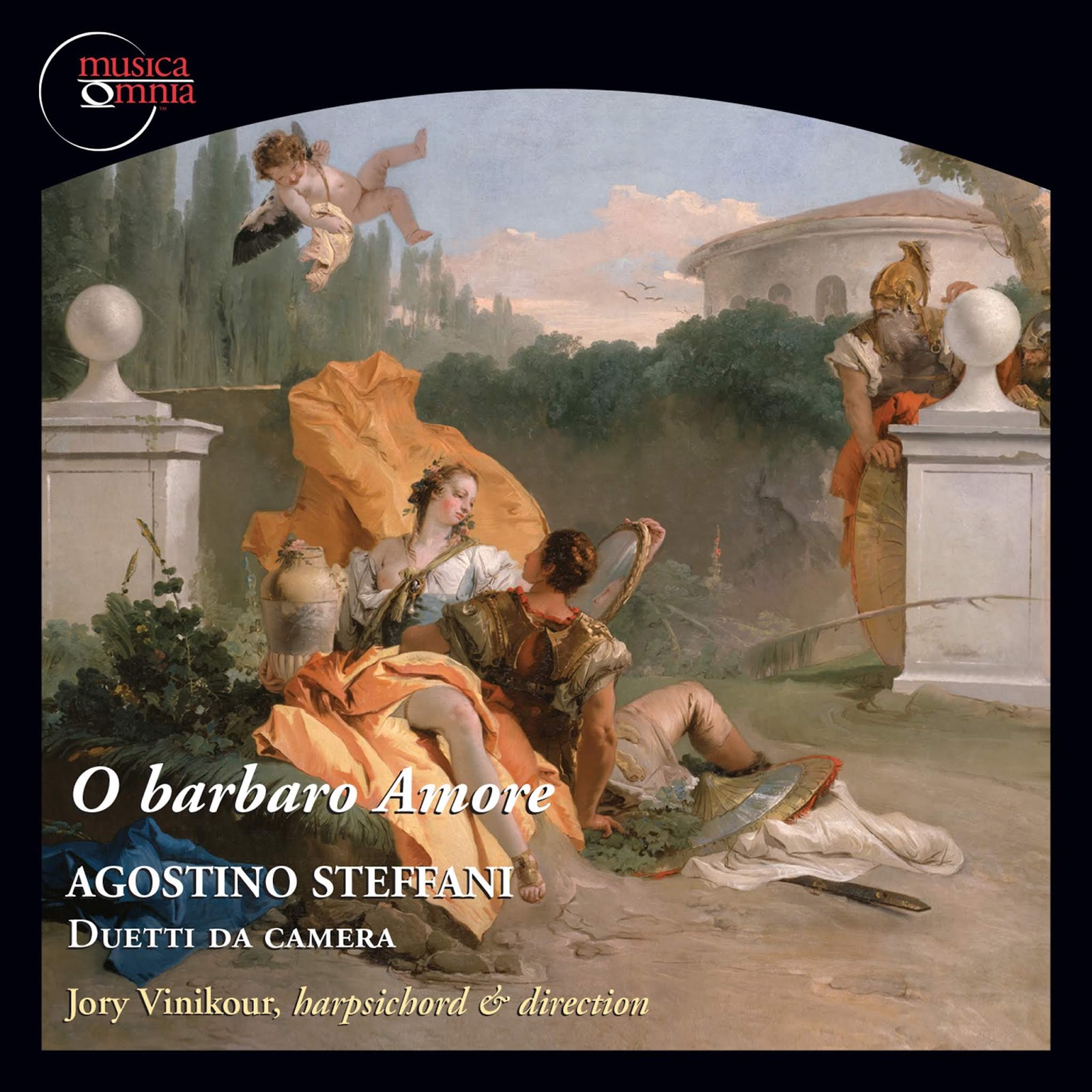

AGOSTINO STEFFANI (1654 – 1728): O barbaro Amore – Duetti da camera—

AGOSTINO STEFFANI (1654 – 1728): O barbaro Amore – Duetti da camera—