![IN REVIEW: sopranos JODI BURNS as Maria Stuarda (left) and YULIA LYSENKO as Elisabetta I (right) in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera] IN REVIEW: sopranos JODI BURNS as Maria Stuarda (left) and YULIA LYSENKO as Elisabetta I (right) in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjRpkDBBNsyEo3x3gr3wArWstRny2POPsOMLk-lZ2inZ8RLhOISu852xwAjzvXYrtuHMlbAumubfypBYw0gEx_grFJmAvJBg78ZteKj9M9r-38ucUJeWJNRdXZnxHqMxwVJ0zuBmn2g2vs/s1600/Donizetti_MARIA-STUARDA_PO_2019_03_Jodi-Burns_Yulia-Lysenko.jpg) GAETANO DONIZETTI (1797 – 1848): Maria Stuarda — Jodi Burns (Maria Stuarda), Yulia Lysenko (Elisabetta I), Kirk Dougherty (Roberto, Conte di Leicester), Jonathan Hays (Sir Giorgio Talbot), Dan Boye (Lord Guglielmo Cecil), Brennan Martinez (Anna Kennedy); Piedmont Opera Chorus, Winston-Salem Symphony Orchestra; James Allbritten, conductor [Steven LaCosse, Stage Director; Howard C. Jones, Designer; Piedmont Opera, The Stevens Center of the UNCSA, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA; Friday, 18 October 2019]

GAETANO DONIZETTI (1797 – 1848): Maria Stuarda — Jodi Burns (Maria Stuarda), Yulia Lysenko (Elisabetta I), Kirk Dougherty (Roberto, Conte di Leicester), Jonathan Hays (Sir Giorgio Talbot), Dan Boye (Lord Guglielmo Cecil), Brennan Martinez (Anna Kennedy); Piedmont Opera Chorus, Winston-Salem Symphony Orchestra; James Allbritten, conductor [Steven LaCosse, Stage Director; Howard C. Jones, Designer; Piedmont Opera, The Stevens Center of the UNCSA, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA; Friday, 18 October 2019]

Insensitive as it may seem, tales of prominent people meeting tragic ends make for great opera. From Dafne’s arboreal metamorphosis and Euridice’s fatal encounter with a serpent to Seneca’s mandated suicide and Sant’Alessio’s martyrdom, opera’s early development relied upon tragic subjects both to inspire composers and to engage audiences. Its emphasis on stories involving deities and royal personages is sometimes cited as evidence of opera’s inherent snobbishness, but the reality is far more practical. Before the modern age ushered in instantaneous global communication, celebrity was an extraordinarily rare commodity. A miller in Tudor England and a blacksmith in Stuart Scotland are unlikely to have possessed any awareness of one another, but both of them may have known of Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots. Its nobler aspirations notwithstanding, opera is entertainment, and is a miller in England more likely to purchase a ticket to be entertained by the story of a Scottish blacksmith who is no more real to him than a mythological beast or the pageantry and passions of queens whose visages grace the coins in his pockets?

When Friedrich von Schiller’s play Maria Stuart was first performed in 1800, 213 years after its subject was beheaded at the behest of Elizabeth I, Mary Stuart retained the admiration and sympathy of much of Catholic Europe, where she was remembered as a proud woman who suffered the indignities of being deprived of her rightful throne, accused of conspiring to usurp the throne occupied by the illegitimate progeny of a heretical king, and executed by a rival with no jurisdiction over her. Like his dramatizations of the lives of Jeanne d’Arc and the Spanish Infante Carlos, both of which received operatic settings from Giuseppe Verdi, Schiller’s account of Mary Stuart’s conflict with Elizabeth I was markedly romanticized, supplementing history with scenes that heighten the story’s theatricality.

![IN REVIEW: tenor KIRK DOUGHERTY as Leicester (left) and soprano JODI BURNS as Maria Stuarda (right) in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera] IN REVIEW: tenor KIRK DOUGHERTY as Leicester (left) and soprano JODI BURNS as Maria Stuarda (right) in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhcN2u8LsZPxP8Hc_hKYN-M31f1NIRDKP6aPXII5SQKHSaOSwjmj5dJd1If4GPcE9w6DZTuXIAswlhfEA8CaCc_xxKikvvJ_myPRv8ctW2W0wf4q2pZnpolj0JVYPY1Lw8VDPcG_RZfcSQ/s1600/Donizetti_MARIA-STUARDA_PO_2019_02_Kirk-Dougherty_Jodi-Burns.jpg) Compagni in periglio: tenor Kirk Dougherty as Leicester (left) and soprano Jodi Burns as Maria Stuarda (right) in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

Compagni in periglio: tenor Kirk Dougherty as Leicester (left) and soprano Jodi Burns as Maria Stuarda (right) in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

[Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]

When rehearsals for the first production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda began in Naples in 1834, the visceral sentiments of Donizetti’s and his seventeen-year-old librettist Giuseppe Bardari’s setting of Schiller’s imagined meeting between Mary and Elizabeth proved to be too personal for the production’s leading ladies. The queens’ vitriol infected the singers, who abandoned musical skirmishing in favor of physical pugilism. Scandal ensued, the queen of Naples, herself a descendant of the Stuarts, objected to the depiction of an ancestor who uttered words like ‘vil bastarda,’ and the censors banished Mary from her own opera. With a new scenario drawn from Dante’s Divina Commedia, the piece was disguised as Buondelmonte, given seven poorly-received performances, and quickly forgotten. On 30 December 1835, Mary regained her crown when Maria Stuarda was first performed in its proper form at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Still admired on the Continent as a paragon of Catholic virtue, Mary thereafter rapidly expanded her domain to include many of Italy’s opera houses.

Maria Stuarda’s performance history in the past century suggests that the New World does not share Europe’s fascination with the eponymous Queen of Scots. [Exacerbated by too-literal supertitle translations, the frequent laughter in Winston-Salem suggested that Twenty-First-Century audiences also have little sympathy for Mary’s plight.] In the decades since the acclaimed 1967 American Opera Society concert performance in New York’s Carnegie Hall with Montserrat Caballé as Maria and Shirley Verrett as Elisabetta, the work has been performed with varying degrees of success in Chicago, New York, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, and elsewhere, but the widespread popularity of L’elisir d’amore, Lucia di Lammermoor, and, in recent years, Don Pasquale and La fille du régiment has eluded Maria Stuarda, which was not heard at the Metropolitan Opera until 2012. Arguably, the most memorable post-World War Two production of Maria Stuarda in the United States was New York City Opera’s 1972 staging, in which Beverly Sills’s Maria sparred with the formidable Elisabette of Pauline Tinsley and Marisa Galvany. Despite a lauded reprise with Sills in 1974, a 2001 Opera Orchestra of New York concert performance with Ruth Ann Swenson and Lauren Flanigan, and a revival in the MET’s current season, Maria Stuarda continues to be an infrequent visitor to America’s opera houses.

![IN REVIEW: mezzo-soprano BRENNAN MARTINEZ as Anna Kennedy in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera] IN REVIEW: mezzo-soprano BRENNAN MARTINEZ as Anna Kennedy in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiKwEwRcJW9A692i1B56kY1iTDmmx4yboW4bF-ybzlc93_xTn0XbBn3usnvDOqeFnAVT67vbhYhW4D3nCxFTRub3Nh08zfx0g92J5qPvkrFzbsupVAVBOotrp8w86tc2xMtefrOROdFehM/s1600/Donizetti_MARIA-STUARDA_PO_2019_01_Brennan-Martinez.jpg) Una vera amica: mezzo-soprano Brennan Martinez as Anna Kennedy in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

Una vera amica: mezzo-soprano Brennan Martinez as Anna Kennedy in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

[Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]

Staging Maria Stuarda is an ambitious endeavor, the work’s musical and scenic complexities making considerable—and costly—demands on an opera company’s resources. The superb quality of Piedmont Opera’s production was therefore both a triumph for regional opera and a vindication of the company’s decision to present this daunting work. Fashionable film and television depictions of Sixteenth-Century England have given many modern observers generalized notions of how life in that era looked and sounded, some of which are of dubious historicity. A high degree of historical accuracy was neither Schiller’s nor Donizetti’s aim, but the collective efforts of costume designer Kathy Grillo, wig and makeup designer Martha Ruskai, scenic designer Howard C. Jones, lighting designer Liz Stewart, and accomplished director Steven LaCosse brought a credible recreation of Elizabeth’s England to the Stevens Center. Costumes were suitably opulent without being so fantastical as to unduly impede movement or vocal production. Likewise, the scenic designs provided visually pleasing environs in which the drama transpired without the distractions of unnecessary scenic minutiae. LaCosse’s direction largely relied upon conventional operatic prancing and posing, but physical motion was an extension of the drama’s emotional currents, forceful but never forced.

It was apparent in his pacing of the company’s March 2019 production of L’elisir d’amore [reviewed here] that Piedmont Opera’s General and Artistic Director James Allbritten is a peer of the world’s finest conductors of bel canto repertoire. Stylistic versatility is a critical component of an opera conductor’s artistry, but the work of few of Allbritten’s colleagues exhibits similar fluency in an array of musical languages. Despite moments of untidy ensemble, the playing of the Winston-Salem Symphony demonstrated clarity and immediacy, the delivery of melodic lines by the woodwinds exemplifying the art of bel canto. Piedmont Opera’s chorus also augmented the aesthetic cultivated by the conductor. Opening Act One with a performance of ‘Qui si attenda, ell’è vicina’ that established an aptly anticipatory atmosphere and singing the Inno della morte in Act Three plaintively, the choristers persuasively imparted all of the points of view assigned to them by Donizetti. Indeed, persuasiveness was the foremost hallmark of this Maria Stuarda: complementing the production team’s achievements, Allbritten paced a performance of compelling bel canto authenticity.

![IN REVIEW: bass-baritone DAN BOYE as Guglielmo Cecil in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera] IN REVIEW: bass-baritone DAN BOYE as Guglielmo Cecil in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgXBYFW-SU1uvk6n5YuVwipMzt07j3bDSYGGLhmpTKnLpG-cw_Nteh-qNSiTvErciLqdJvTaWbBQnrClTZ1w91DjU0mFWEVhBAQAzo1lKo7HySN55Ro16tJBPxqk8DWMQ5EDsHi04QfO98/s1600/Donizetti_MARIA-STUARDA_PO_2019_06_Dan-Boye.jpg) Ministro della morte: bass-baritone Dan Boye as Guglielmo Cecil in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

Ministro della morte: bass-baritone Dan Boye as Guglielmo Cecil in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

[Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]

As Maria’s companion and confidante Anna Kennedy, mezzo-soprano Brennan Martinez sang incisively, her musicality, dramatic sincerity, and youthful tone making a strong impression despite the brevity of her part. Compared with Anna, the implacable Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lord Guglielmo Cecil, offers his interpreter more opportunities to display his prowess as a singing actor. Especially in the Act Three duet in which Cecil entreats Elisabetta to sign Maria’s death warrant and the scene in which he callously informs Maria of her condemnation and imminent execution, bass-baritone Dan Boye sang boldly, hurling out Cecil’s hateful words with histrionic power that was only marginally lessened by unmistakably non-native Italian diction. Nonetheless, the maleficence of his characterization overcame occasional weaknesses in his vocalism, revealing Cecil as the true author of Maria’s fate.

![IN REVIEW: baritone JONATHAN HAYS as Giorgio Talbot in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera] IN REVIEW: baritone JONATHAN HAYS as Giorgio Talbot in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiDRFhTwZoKF1cbnzx-BgPmrtZXv-5m_J4UbVSpDYPnZMvaTfWRHIvWBnCxJGJ8xihEjqm0WjX_dYpskqVG1bzeMyIbO4aXLD9lDM-OyZbw7SenO-PmnTlDx6l6RSVwfVwpPtPMG0SIWmY/s1600/Donizetti_MARIA-STUARDA_PO_2019_05_Jonathan-Hays.jpg) Conte fedele: baritone Jonathan Hays as Giorgio Talbot in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

Conte fedele: baritone Jonathan Hays as Giorgio Talbot in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

[Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]

Baritone Jonathan Hays’s portrayal of Giorgio Talbot, the Earl of Shrewsbury, evinced pervasive empathy for Maria. He voiced ‘Questa imago, questo foglio’ in the Act One duet with Leicester with suavity, his virile, flinty timbre lending his utterances a paternal sincerity. Even finer was his command of legato in the Act Three confession scene with Maria, contrasting meaningfully with his emphatic singing of conversational passages. Humbled by his recognition of Maria’s innocence and the dignity with which she accepts her impending death, Hays’s Talbot touchingly prefaced the doomed queen’s prayer with a heartfelt blessing of her final hours on earth. Throughout the performance, Hays conveyed the frustration of a benevolent man who finds himself on the edge of a precipice and unable to prevent those for whom he cares from plunging into the abyss.

![IN REVIEW: tenor KIRK DOUGHERTY as Leicester in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera] IN REVIEW: tenor KIRK DOUGHERTY as Leicester in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhBn_qC5HTpPK9W1AUGZxzmMEKRsOXXbyX1AQ-ydOrnGD89wVrEfEO6Apcgl_cc3XyVsvJQns7tF9usamEXvQoTCrLUMZOFn-8nauen16CCyzNDvkjQNPBck67RguWNDp6aBYMcQ9vhrms/s1600/Donizetti_MARIA-STUARDA_PO_2019_08_Kirk-Dougherty.jpg) Difensore della virtù: tenor Kirk Dougherty as Leicester in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

Difensore della virtù: tenor Kirk Dougherty as Leicester in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

[Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]

Adaptability to a broad assortment of musical styles is as important to a modern singer’s success as to that of a conductor, and tenor Kirk Dougherty excels in repertoire ranging from bel canto to Pinkerton in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly and Nikolaus Sprink in Kevin Puts’s Silent Night, the last of which he sang to acclaim in Piedmont Opera’s 2017 production. Returning to Winston-Salem as Roberto Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, in Maria Stuarda, Dougherty infused the performance with febrile romantic ardor. Attempting to assuage Elisabetta’s antipathy towards Maria in his first scene in Act One, this Leicester pleaded without whining, Dougherty’s vocalism firm and focused. His impassioned account of ‘Ah! rimiro il bel sembiante’ disclosed the depth of Leicester’s affection for Maria, and his fervent singing in the subsequent duet with Talbot, ended with a splendid top C, reiterated the Earl’s commitment to shielding Maria from Elisabetta’s ire. Dougherty mellifluously caressed the melodic line of ‘Era d’amor l’immagine’ in the duet with Elisabetta, but his resonant top B was a reminder of his dogged determination.

The tenor’s singing in Act Two was no less galvanizing, not least in the duet with Maria and the superb sextet, nearly the equal of its better-known counterpart in Lucia di Lammermoor, but it was in the Act Three terzetto with Elisabetta and Cecil that Dougherty was at his best, articulating ‘Ah, deh! per pietà sospendi’ with irrepressible despair. There and in the opera’s final scene, as Leicester grappled with his inability to alter the course of Maria’s destiny, Dougherty’s singing was shaded by moving morbidezza. Unfortunately, his voice did not project into the auditorium with ideal freedom and was sometimes covered by the orchestra, but he consistently sang well and believably portrayed a man who loves one queen and is loved by another.

![IN REVIEW: soprano YULIA LYSENKO as Elisabetta I in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera] IN REVIEW: soprano YULIA LYSENKO as Elisabetta I in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjBdN1UYTKAcUXkrHD0HRvH81kYe1Dymz1CyRYUDqDQEQe_N1oH6b7g0z2W_tc5D1AolCzm4Mt6w3zO5CZGieQU5AsA70hRHQBXX8AwxtefDmCIgFWoUiO6mmjYk0lJtTyLDpnlKkkGcg4/s1600/Donizetti_MARIA-STUARDA_PO_2019_07_Yulia-Lysenko.jpg) Regina della crudeltà: soprano Yulia Lysenko as Elisabetta I in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

Regina della crudeltà: soprano Yulia Lysenko as Elisabetta I in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

[Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]

With the casting of soprano Yulia Lysenko, previously heard in Winston-Salem as Mimì in Puccini’s La bohème, as Elisabetta, Piedmont Opera strengthened Maria Stuarda’s dramatic thrust with a fierce antagonist who was more dangerous because her ferocity masked vulnerability. At her entrance in Act One, this Elisabetta’s demeanor betrayed none of the uncertainty that plagued the monarch throughout her reign. Lysenko’s performances of the cavatina ‘Ah! quando all’ara scorgemi’ and cabaletta ‘Ah! dal cielo discenda un raggio’ radiated regal—and vocal—confidence, epitomized by the soprano’s resplendent top B. Her singing in the duet with Leicester divulged Elisabetta’s jealousy and pettiness but also declared the breadth of her unrequited love for the Earl.

In Act Two, Lysenko launched the sextet electrifyingly and unleashed a cyclone of fury in the confrontation scene. Her enunciation of ‘Quella vita me funesta io troncar’ in the Act Three duet with Cecil asserted that this Elisabetta was keenly aware of the Chancellor’s unyielding manipulation. Lysenko’s voice soared in the terzetto with Leicester and Cecil. The soprano’s unaffected execution of Elisabetta’s hesitant, pained exit after signing Maria’s death warrant was unexpectedly gripping and received an ovation from the audience. Lysenko avoided employing chest resonance in virtually all of her music, depriving the lowest notes of the part of requisite muscle, but the brilliance of her upper register, the vigor of her singing of bravura passages, and the acuity of her acting offered ample compensation.

![IN REVIEW: soprano JODI BURNS in the title rôle in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera] IN REVIEW: soprano JODI BURNS in the title rôle in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgKzy8_sbZsA9VbGvmvFnW_0Zliihr8PkB0Y90Y1dvTHApecnFbVdJlOdwYIs-bkL_EORv5bhMBujb5hIitXcQ9kw3Hvdx8eu6VveX_qylQ4AbpNLwHsGpKHVJs4w0joMTwKXccbdpiiSc/s1600/Donizetti_MARIA-STUARDA_PO_2019_04_Jodi-Burns.jpg) Bontà incoronata: soprano Jodi Burns in the title rôle in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

Bontà incoronata: soprano Jodi Burns in the title rôle in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

[Photograph © by André Peele & Piedmont Opera]

First heard in Act Two [the latter half of Act One in Piedmont Opera’s production], Maria makes her entrance with a scene in which, in the only period of relative tranquility that she enjoys in the opera, she muses on her far-from-idyllic but happy youth in France. From the first bars of her traversal of the cavatina ‘O nube! che lieve per l’aria ti aggiri,’ Jodi Burns was a Maria in the class of the most gifted interpreters of the rôle, her performance recalling Leyla Gencer’s fearlessness, Montserrat Caballé’s glorious pianissimi, Beverly Sills’s purity of line, and Sondra Radvanovsky’s absolute immersion in the drama. The ebullience of Burns’s singing of the cabaletta ‘Nella pace del mesto riposo’ fostered a mood of guarded optimism.

Maria’s elation at Leicester’s arrival was destroyed by his news that Elisabetta was close at hand, having come at his urging to meet Mary in the flesh. In the duet with Leicester, Burns first sang ‘Da tutti abbandonata’ with wrenching simplicity, her Maria genuinely lamenting her situation rather than indulging in self-pity, and then declaimed ‘Ah! Se il mio cor tremò giammai’ with renewed resolve. Her lines in the sextet were always audible and engendered a righteous aloofness that set Maria apart from the vengeful Elisabetta. The celebrated ‘dialogo delle due regine’ spurred Burns to singing of incredible energy and dramatic potency. She exclaimed the stinging ‘figlia impura di Bolena’ and ’vil bastarda’ with startling spontaneity, warranting the look of shocked vexation that flashed across Elisabetta’s face. As the English queen haughtily left the stage, Burns brought the curtain down with a magnificently defiant and cathartic top D.

Whether designated as Act Two, as in Piedmont Opera’s production, or as Act Three, the concluding scenes of Maria Stuarda constitute one of the most remarkable sequences in Italian opera. Burns’s Maria received Cecil‘s proclamation of her sentence with stoicism, but a spark of umbrage ignited her response to his spiteful suggestion that she meet with a Protestant minister in order to be reconciled with God. Exercising her faith on her own terms in the eloquent ‘duetto della confessione’ with Talbot, this Maria voiced ‘Quando di luce rosea’ ravishingly. In Burns’s performance, wonderfully supported by the chorus, the preghiera ‘Deh! tu di un umile preghiera il suono’ was exquisite. Her voicing of the ‘aria del supplizio,’ ‘D’un cor che muore reca il perdono,’ was phrased with innate understanding of bel canto.

After performing the repeats of the foregoing cabalette, omitting the repeat of ‘Ah! se un giorno da queste ritorte’ was regrettable, especially as Burns’s ornamentation of her music was unfailingly tasteful, but excising the repeat undeniably produced a more abrupt conclusion that significantly increased the emotional tension of the final scene. Apart from a pair of very brief instances in which high pianissimi threatened to crack, Burns’s vocal control was impeccable, and the tonal beauty that she brought to Maria’s music was profoundly satisfying. The essence of bel canto is beauty of expression, however, and Burns brought one of the most difficult rôles in the soprano repertoire to life with the kind of unfeigned expressivity and pathos of which only true artists are capable.

There is a pertinent scene in Miloš Forman’s cinematic adaptation of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus in which Mozart, at work on an opera about a servant and his fiancée, and representatives of the imperial musical establishment debate the importance of operatic subject matter. Does an audience’s ability to relate on some psychological level with the characters on stage determine an opera’s theatrical viability or intrinsic artistic value? More than four centuries after the death of its heroine, can an Italian composer’s operatic setting of a German playwright’s dramatization of the enmity between an English queen and her Scottish contemporary possibly hold any significance for American audiences in the Twenty-First Century? Piedmont Opera’s Maria Stuarda avowed that opera’s vitality is defined not by the characters who populate it but by the feelings that they portray and inspire. It is unlikely that anyone who experiences Piedmont Opera’s Maria Stuarda can relate to a queen’s tribulations, but, whether wearing priceless diamonds or dime-store pearls, who cannot relate to feelings of love, loss, fear, and freedom?

♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫

Additional performances of Piedmont Opera’s production of Maria Stuarda are at 2:00 PM on Sunday, 20 October 2019, and at 7:30 PM on Tuesday, 22 October.

![Soprano JODI BURNS, the eponymous Queen in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by Jodi Burns] Soprano JODI BURNS, the eponymous Queen in Piedmont Opera's October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti's MARIA STUARDA [Photograph © by Jodi Burns]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhYXMkle1Kawek_Om7bMSPafg6F6mVSxhMPpbellmuD6zvokS2oFPkMKyJ1JXG8FRgXhXJBEtHJtx3yNVMfX7ezO9MhDzR55-aowLUHRdTlSv1VzM-zi5tLAtCvfvz9zO7bjZsVZraRKVM/s1600/Jodi-Burns_UNCSA.jpg) Ecco la regina: Soprano Jodi Burns, interpreter of the title rôle in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda

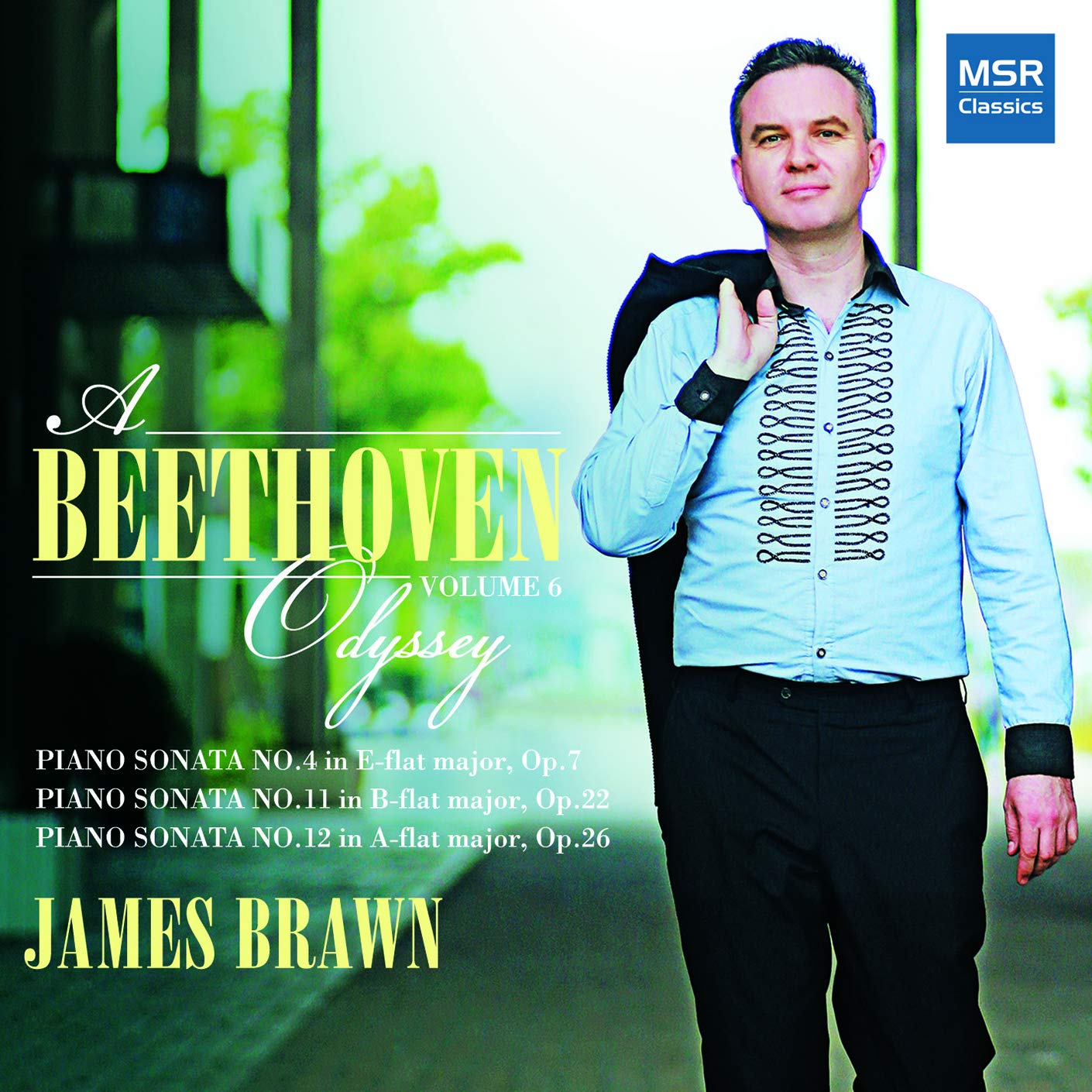

Ecco la regina: Soprano Jodi Burns, interpreter of the title rôle in Piedmont Opera’s October 2019 production of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770 – 1827): A Beethoven Odyssey, Volume Six – Piano Sonatas Nos. 4 in E♭ major (Opus 7), 11 in B♭ major (Opus 22), and 12 in A♭ major (Opus 26) —

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770 – 1827): A Beethoven Odyssey, Volume Six – Piano Sonatas Nos. 4 in E♭ major (Opus 7), 11 in B♭ major (Opus 22), and 12 in A♭ major (Opus 26) — ![ARTS IN ACTION: Soprano OTHALIE GRAHAM, Lady Macbeth in Opera Carolina's November 2019 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by the artist] ARTS IN ACTION: Soprano OTHALIE GRAHAM, Lady Macbeth in Opera Carolina's November 2019 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by the artist]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgWwyLpjrxjAZ3yfDSOzbkpNsnJOcGYjqzRbGTXp5ouuccK4f_OFAzVSaXQM5rJibgVmmSA2oSfNgapUd1bs76LzHsqltt0McbSiH0JEUqWEXgtLyd3joBnxOoUOLykSMtPOFqL_PcDHlw/s1600/Othalie-Graham.jpg) Lady of the hour: soprano Othalie Graham, Lady Macbeth in Opera Carolina’s November 2019 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth

Lady of the hour: soprano Othalie Graham, Lady Macbeth in Opera Carolina’s November 2019 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth![ARTS IN ACTION: mezzo-soprano GRACE BUMBRY as Lady Macbeth in Los Angeles Music Center Opera's 1987 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by Los Angeles Music Center Opera; image from the Detroit Public Library collection] ARTS IN ACTION: mezzo-soprano GRACE BUMBRY as Lady Macbeth in Los Angeles Music Center Opera's 1987 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by Los Angeles Music Center Opera; image from the Detroit Public Library collection]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiJNGH0jobw_tT-mFL_ExmRIawx7Z4WNW7sC6cXQXk5_Ul7g1kwoZNOp0lElsTUQsIl4G4Rc-c7lVoNQsd6brtq5EwnC5AK_B0UfjCFJxohzDjRJBPgobg8K2dhhSdLUykS0NiDT3aSFXM/s1600/Verdi_MACBETH_Grace-Bumbry_Los-Angeles-Music-Center-Opera_1987.jpg) La luce langue: mezzo-soprano Grace Bumbry as Lady Macbeth in Los Angeles Music Center Opera’s 1987 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth

La luce langue: mezzo-soprano Grace Bumbry as Lady Macbeth in Los Angeles Music Center Opera’s 1987 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth![ARTS IN ACTION: mezzo-soprano SHIRLEY VERRETT as Lady Macbeth (left) and baritone RYAN EDWARDS as Macbeth (right) in Boston Opera Company's 1976 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by Boston Opera Company] ARTS IN ACTION: mezzo-soprano SHIRLEY VERRETT as Lady Macbeth (left) and baritone RYAN EDWARDS as Macbeth (right) in Boston Opera Company's 1976 production of Giuseppe Verdi's MACBETH [Photograph © by Boston Opera Company]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiGz-rBLRNbKeDIZLPN-3CtH8OI3mSaFI-6-QIpiFRmIM8X7T5rV8ruTu2bikXw5LUf3CIktbjuU2KI65uIJBxW2kKeEKb8pFOblRAJHSZni-83SxRXt_7sHdcZLX2s9feFhYUNb7GVlRM/s1600/Verdi_MACBETH_Shirley-Verrett_Ryan-Edwards_Boston-Opera_1976.jpg) Fatal mia donna: mezzo-soprano Shirley Verrett as Lady Macbeth (left) and baritone Ryan Edwards as Macbeth (right) in Boston Opera Company’s 1976 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth

Fatal mia donna: mezzo-soprano Shirley Verrett as Lady Macbeth (left) and baritone Ryan Edwards as Macbeth (right) in Boston Opera Company’s 1976 production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth