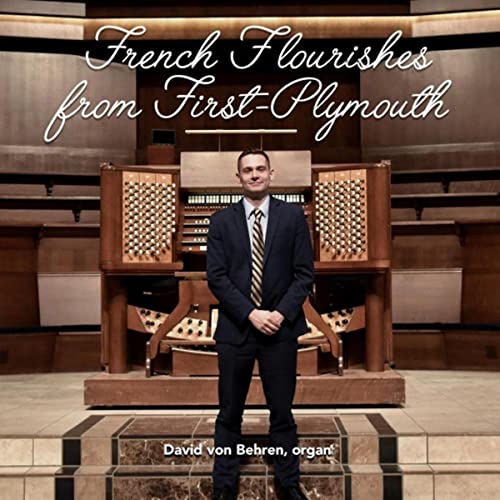

MARCEL LANQUETUIT (1894 – 1985), LOUIS-CLAUDE DAQUIN (1694 – 1772), CÉSAR FRANCK (1822 – 1890), NAJI HAKIM (born 1955), NADIA BOULANGER (1887 – 1979), and CHARLES-MARIE WIDOR (1844 – 1937): French Flourishes from First-Plymouth — David von Behren, organ [Recorded in First-Plymouth Congregational Church, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA; David von Behren Music; 1 CD / Digital download, 43:15; Available from Amazon, Apple Music, Deezer, and major music retailers and streaming services]

MARCEL LANQUETUIT (1894 – 1985), LOUIS-CLAUDE DAQUIN (1694 – 1772), CÉSAR FRANCK (1822 – 1890), NAJI HAKIM (born 1955), NADIA BOULANGER (1887 – 1979), and CHARLES-MARIE WIDOR (1844 – 1937): French Flourishes from First-Plymouth — David von Behren, organ [Recorded in First-Plymouth Congregational Church, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA; David von Behren Music; 1 CD / Digital download, 43:15; Available from Amazon, Apple Music, Deezer, and major music retailers and streaming services]

In the history of Western music since the dawn of the Renaissance, extraordinary artistic genius has often manifested in composers whose prowess as organists paralleled their creative gifts. Dieterich Buxtehude’s, Johann Pachelbel’s, Johann Sebastian Bach’s, Georg Friedrich Händel’s, and Anton Bruckner’s reputations as organists are widely known and abundantly evident in their writing for the instrument, but the artistic journeys of composers as diverse as Francesco Cavalli, Camille Saint-Saëns, Olivier Messiaen, and Sir Michael Tippett were also influenced by their work as organists. An instrument capable of both monumental grandeur and entrancing intimacy, and one with intrinsic associations with spirituality for many listeners, the organ is a microcosm in which all of the colors of the orchestra and all of the nuances of human expression coexist. The rare convergences of great composers, great music, great organs, and great organists reveal the power of music in its purest form: an instrument, complex in its construction but gloriously simple in its impact, and the individual entrusted with administering its sounds become storytellers whose tales require no words.

Recorded in the inspiring space of First-Plymouth Congregational Church in Lincoln, Nebraska, French Flourishes from First-Plymouth employs one of America’s finest instruments, California-based Schoenstein and Company’s Lied Chancel organ, the more than 6,000 pipes of which encompass nine divisions and are enriched by 110 ranks and eighty-five stops, producing a panoply of voices ranging from dulcet lyricism to roaring splendor that rivals the most celebrated European organs. The instrument finds in David von Behren, a graduate of Cleveland Institute of Music and Yale University, doctoral candidate at Boston University, and Assistant Organist and Choirmaster at Memorial Church of Harvard University, an artist whose sensibilities are ideally suited to the instrument’s capacity for alternating brilliance with introspection.

Also an accomplished violinist, von Behren plays the ‘French flourishes’ on this expertly-produced recording with technical acumen that dazzles only in retrospect: as he plays, it is the profundity of his interpretive instincts rather than his meticulously-honed technique that awes. The unique sonic profile of a consequential organ within the aural environment that it was designed to inhabit is impossible to capture on a recording with absolute fidelity, but this young organist’s performance transforms the listener’s headphones or speakers into a pew in First-Plymouth’s sanctuary, from which one can contemplate the relationship between a gifted musician and a notable instrument much as Leipzigers must have done when Bach was at the console.

Opening his sagaciously-programmed and thoughtfully-ordered recital with Marcel Lanquetuit‘s engaging Toccata in D major, a piece with much in common with the organ music of the composer’s countrymen Édouard Batiste and Déodat de Séverac, von Behren establishes a celebratory atmosphere, integrating the work’s difficulties into a joyous realization of the music’s oft-neglected humor. The skill with which navigations of manuals and pedals are handled throughout the performances on French Flourishes is immediately apparent, but it is the emotional dexterity with which the Toccata’s challenges are met that distinguishes von Behren’s playing. This performance of the Toccata intensifies the futile longing for more of Lanquetuit’s music to have survived unto the Twenty-First Century.

During an illustrious career in the French capital, Louis-Claude Daquin was organist at Église Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis, the Chapelle Royale, and Notre-Dame de Paris, for the first of which posts he successfully competed with Jean-Philippe Rameau. Though considerably more of his music is preserved, Daquin shares with Lanquetuit the dubious distinction of being assessed primarily on the merits of a single work. The tenth of the Noëls, ‘Noël, Grand Jeu et duo,’ from that work, his Opus 2 Nouveau livre de Noëls, receives from von Behren a traversal that respects the parameters of period-appropriate playing without being restricted by them. The galant style prevalent in French organ music during the first half of the Eighteenth Century permeates Daquin’s writing, but von Behren’s aptly jubilant account of the Noël also discloses unanticipated modernity in deftly-managed harmonic progressions.

At the age of thirty-five, César Franck was named principal organist at the twin-spired Basilique Sainte-Clotilde in Paris’s seventh arrondissement, a post that he held and from which he guided the development of French Romantic writing for the organ for the remaining thirty-two years of his life. Widely acclaimed in the Nineteenth Century, many of Franck’s works for organ remain staples of organists’ repertoires. For French Flourishes, von Behren chose one of the compositions that, though written in Franck’s early years in Paris, were first published in a posthumous collection fifteen years after his death. Representative of Franck’s most beguilingly inventive creations for organ, the Sortie «Laissez paître vos bêtes» (’Venez, divin Messie’) is characterized by melodic succinctness typical of its composer. Attentive to Franck’s tonal textures, von Behren phrases his performance with a Lieder singer’s sensitivity to the psychological significance of dynamics and rhythms. In the Sortie’s final bars, he engenders true resolution, meaningfully contrasting the element of catharsis in the piece’s coda with the aura of harmonic ambiguity found in many works dating from the first decade of Franck’s tenure at Basilique Sainte-Clotilde.

Like the Belgian-born Franck, Naji Hakim brings aspects of another nation’s cultural perspectives to French organ music, his work fusing Western traditions with echoes of the vibrant musical milieux of his native Lebanon. Crafted so that they can be assimilated into the Roman Rite of the Mass (in the Introitus, Offertorio, Elevation of the Host, Communion, and Sortie, respectively), Hakim’s Esquisses grégoriennes rhapsodize themes drawn from plainsong, metamorphosing the monophonic sequences into discourses between old and new. The first of Hakim’s plainchant paraphrases, the ‘Nos autem,’ is played with focus on the composer’s ingenious musical response to the liturgical text that it limns. The surging momentum of the ‘Ave maris stella,’ maintained by von Behren with unfaltering rhythmic accuracy, yields to heartfelt solemnity in the ‘Pater noster,’ approached in this performance as a discernibly personal, sincere devotion. Hakim’s adaptation of the ‘Ave verum’ allies eloquence with innovation, and von Behren utilizes the First-Plymouth organ’s intonational clarity to accentuate the cleverness of the composer’s treatment of the chant. The beauties of ‘O filii et filiæ’ are heightened by the unaffected expressivity of von Behren’s playing, his commitment to precision never obscuring the feeling with which he interprets the music.

Few musical personalities of any epoch have exerted greater influence as concertizing musician, theorist, and pedagogue than Nadia Boulanger, whose own compositions exhibit the same adventurousness evident in her indefatigable championing of the work of her contemporaries. Boulanger’s Trois pièces pour orgue were written in 1911, not long after the young composer, still in her mid-twenties, attended the première of The Firebird and befriended Igor Stravinsky. The early date of its composition notwithstanding, a mature artistic idiom emerges in Boulanger’s Prélude, particularly when it is performed with the delicacy that von Behren brings to it. His gossamer negotiations of the contrapuntal meanderings of the Petit Canon wholly avoid academic lugubriousness, paying homage to Boulanger’s daring substitution of a fugue for instrumental ensemble for the requisite vocal fugue when vying for the Grand Prix de Rome in 1908. Von Behren’s gift for musical portraiture fashions an Improvisation in which Boulanger’s inimitable persona wields timeless charisma.

Since the completion of Charles-Marie Widor’s Symphony No. 5 in F minor (Opus 42, No. 1) in 1879, the work’s dizzyingly virtuosic Toccata has served as a vehicle for showmanship for virtually every organist capable of playing it. This is music in which adequacy is admirable, but von Behren again displays affinity for eschewing convention and devising his own solutions for musical conundra. Instead of the breakneck speeds at which some organists attempt to play the Toccata, von Behren adopts—and, crucially, sustains—a tempo that facilitates crisp articulation of the profusion of semiquavers and arpeggios that decorate the piece’s underlying subject. The mercurial modulations that are sometimes a sonic muddle are here uncommonly clean. The piece’s undulating journey to the boundaries of Romantic tonality is therefore prophetic rather than frenetic, anticipating the progressive tonalities of Gustav Mahler’s symphonies. The Toccata is daunting at any pace, however, and von Behren plays it rousingly.

Legend attributes the invention of the organ to the Third-Century Roman martyr Saint Cecilia, still revered as the patroness of music and organists. This detail of the saint’s hagiography likely resulted from a mistranslation that proved too beloved to correct, but performances by important organists can convince listeners that, whatever the provenance of its origins may be, the organ is a divine gift. Allowing listeners far from Nebraska to experience the might of an instrument with few rivals in North America, French Flourishes from First-Plymouth is also a gift. However wondrous its design, the grandest organ is merely a lifeless body until a conscientious musician revives its pulse, the player’s heart becoming that of the instrument. His musicianship is formidable, but it is the heart with which he plays that marks David von Behren as a poet of the pipes.