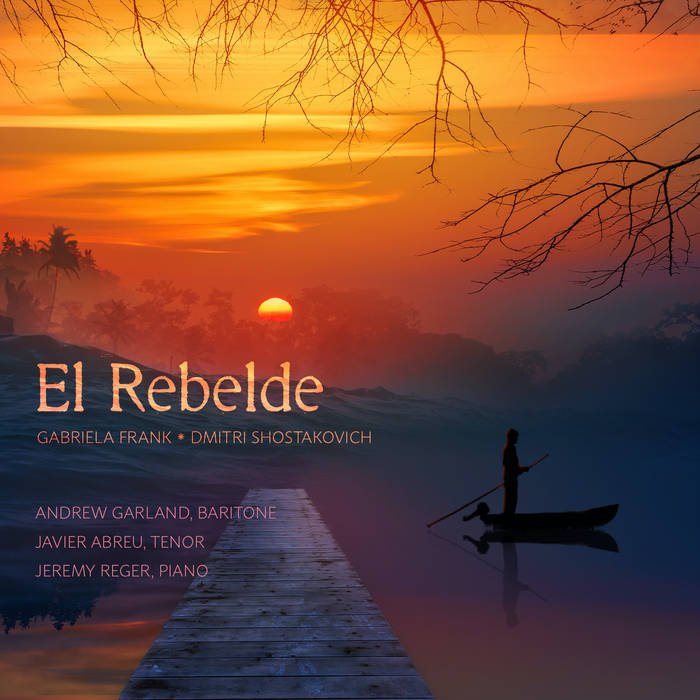

GABRIELA LENA FRANK (born 1972) and DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906 – 1975): El rebelde — Andrew Garland, baritone; Javier Abreu, tenor; Jeremy Reger, piano [Recorded in Grusin Recital Hall, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA, 23 – 26 May 2022; Art Song Colorado DASP 005; 1 CD, 68:31; Available from Kunaki, Amazon (USA), Bandcamp, Spotify, and major music retailers and streaming services]

GABRIELA LENA FRANK (born 1972) and DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906 – 1975): El rebelde — Andrew Garland, baritone; Javier Abreu, tenor; Jeremy Reger, piano [Recorded in Grusin Recital Hall, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA, 23 – 26 May 2022; Art Song Colorado DASP 005; 1 CD, 68:31; Available from Kunaki, Amazon (USA), Bandcamp, Spotify, and major music retailers and streaming services]

Technologies like streaming audio and online archives make exploring and absorbing musical traditions of diverse cultures easier now than ever before, yet many listeners’ musical acquaintances with Spanish-speaking communities are still engendered by works like Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia, Bizet’s Carmen, Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole, and Ravel’s Bolero—music, that is, written by composers with no or tenuous ties to the Hispanic diaspora. Art Song aficionados know cornerstones of the Spanish song repertoire such as Manuel de Falla’s Siete canciones populares españolas and Granados’s Canciones españolas, but what are the ratios of new recordings of songs in Spanish of any level of familiarity to further accounts of Schubert’s Winterreise and Schumann’s Dichterliebe?

A rare trek into the expansive realm of songs by an authentic Spanish-speaking composer and one of other origins who surrendered to the allures of Latin forms, baritone Andrew Garland’s Art Song Colorado recording El Rebelde is precisely what its title proclaims it to be: a rebel. Rejecting the confines of the conventional Spanish-language repertoire that an enterprising vocal artist should sing, Garland and his colleagues rebelliously both extend the boundaries of that body of work by introducing listeners to a collection of songs by a contemporary Latinx composer and rejuvenate too-seldom-performed arrangements of Spanish themes by one of the Twentieth Century’s most celebrated composers. The baritone’s partner in this ambitious voyage, pianist Jeremy Reger, articulates the quixotic transitions of mood and rhythm not with the halting step of a traveler in little-visited territory but with a native’s unflappable confidence, lighting the fuses of the dynamic performances with which Garland obliterates dated notions of what constitutes ‘serious’ Spanish song.

A native Californian whose global ethnic heritage includes Peruvian ancestry, composer Gabriela Lena Frank demonstrates in the pieces included on El Rebelde that she is an innovator whose songwriting encompasses creative uses of interplay between voice and piano and comprehensive knowledge of an array of vocal styles. The eight of her Cantos de Cifar y el Mar Dulce presented on this recording reflect progress in her initiative to provide music for all thirty of Pablo Antonio Cuadra’s Cantos. In these eight songs, Frank creates a remarkable spectrum of aural textures, ranging from serene lyricism to biting dissonance. Propelled by the sharply-defined rhythmic profile of Reger’s pianism, Garland sings the opening Canto, ‘El nacimiento de Cifar,’ engagingly, immediately creating an aura of exotic tension that lures the listener into the intricacies of music and text. A sense of savagery permeates the performance, singer and pianist shrinking from none of the irony and ferocity in the music. Nevertheless, there is tenderness amidst the vehemence of Garland’s voicing of ‘Me diste (¡oh Dios!) una hija,’ his jagged phrasing imparting the psychological intensity of the text.

The song from which the recording takes its title, ‘El rebelde,’ is sung with unapologetic bravado, the baritone relishing every non-Classical vocal effect and assault on the upper register. Frank’s writing often asks the singer to integrate a populist sound recalling Ibrahim Ferrer with a Verdi baritone’s top notes, and Garland rises to the task unflinchingly. His accounts of ‘Tomasito, el cuque’ and ‘El niño’ create a palpable narrative, heightened by Reger’s virtuosic deployment of the piano’s arsenal of piquant sounds, and they achieve a striking contrast with a profoundly expressive traversal of ‘Eufemia.’ Likewise, the conflicting but uncannily complementary subtlety and abrasiveness of ‘En la vela del Angelito’ and ‘Pescador’ are affectingly limned, each word projected with cognizance of its significance in the songs’ cumulative contexts.

Frank’s Peruvian roots blossom resplendently in Cuatro Canciones Andinas, a group of songs utilizing José María Arguedas’s Spanish translations of texts by the Quechua people, from whose ranks the Inca civilization arose. The music pulses with sonic evocations of the rugged landscapes of the Cordillera Oriental, evincing the imposing peaks’ ambiguities as both hardship and safe harbor for Peru’s indigenous peoples. As performed by Garland and Reger, ‘Despedida’ is all the more touching for their unerring avoidance of saccharine affectation. They also approach ‘Yo crio una mosca’ with sobriety rather than sentimentality, allowing the song’s text to make its own impressions. The ebullience of ‘Carnaval de Tambobamba’ crackles in both the voice and the piano, the music’s innate energy made palpable to the listener. Unmistakable, too, are the enchanting beauties of ‘Yunca,’ uplifted by the abiding luster of Garland’s tones.

A setting of verses by Nilo Cruz that address the 1936 murder of Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, ‘Las cinco lunas de Lorca’ is an extended duet for tenor and baritone. Reminiscent in structure to Verdi’s scenes for the eponymous prince and Rodrigue in Don Carlos, Frank’s writing for the voices grippingly manifests the brutality and pathos of Lorca’s demise. Garland and Reger are joined in this performance by tenor Javier Abreu, whose polished-silver voice blends well with the garnet hues of Garland’s singing. Together, they recount Lorca’s harrowing assassination with discernibly personal depth, singing as though they lament the cruel silencing not of a distant historical figure but of a lifelong friend.

Written at the request of Armenian mezzo-soprano Zara Dolukhanova, who shared a selection of traditional Spanish tunes with the composer with the hope of inspiring a complex recital piece for her own repertoire, and first published in 1956, Dmitri Shostakovich’s Opus 100 Spanish Songs adhere to the rhythms and cadences of the folk tunes from which they were derived. Dolukhanova was disappointed by the songs, but Garland’s performance of them validates the wisdom of Shostakovich’s decision to arrange the songs without adornments. Enunciating the Russian text with clarity, Garland voices ‘Прощай, Гренада!’ powerfully, his vocal strength allied with interpretive intuition.

As the songs progress, Shostakovich is proved to have preserved the Spanish flavor of the songs so masterfully that the language in which they are sung is irrelevant. Still, reacting to the voice’s discourse with the piano, Garland’s singing of ‘Звёздочки’ is driven by the words. He and Reger communicate the vastly different feelings of ‘Первая встреча’ and ‘Ронда’ with meticulous specificity. Their attention to the details of each phrase yields performances of ‘Черноокая’ and ‘Сон’ in which the Spanish soul of the songs and the essence of Shostakovich exuded by his late symphonies and chamber music are equally prominent.

Music has a wondrous legacy of rebellion. Works like Auber’s La muette de Portici and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring have sparked philosophical conflagrations that incinerated tired institutions and systems of thought. In innumerable smaller ways, music alters perspectives and fords seemingly unnavigable rivers of division. The choices of repertoire alone make El Rebelde worthy of its title, but the necessary revolution here is the refusal to accept simplistic conceptions of Hispanic identity. The Latinx spirit dwells wherever it is invited in, and few invitations are as irresistible as Andrew Garland’s singing of this music.