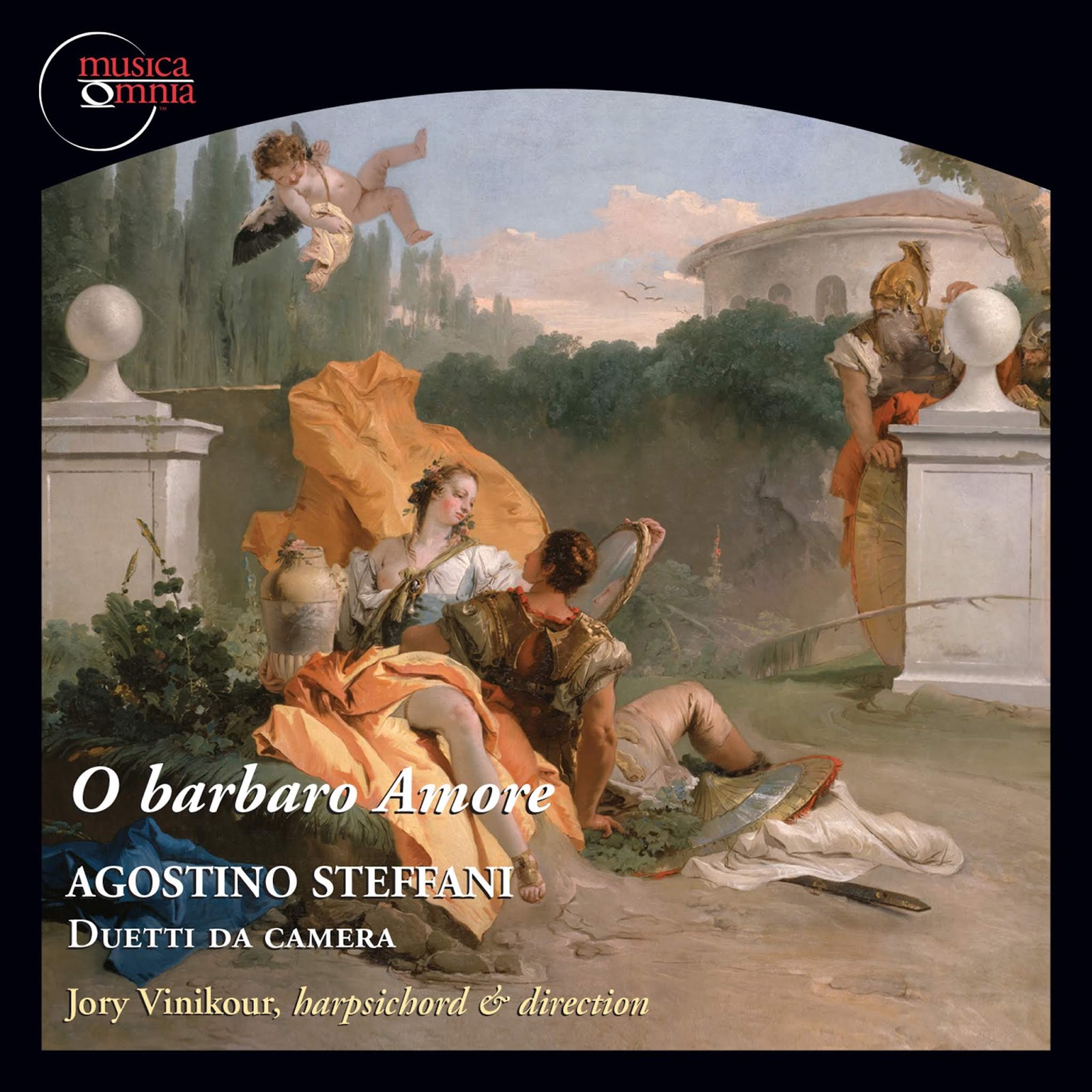

AGOSTINO STEFFANI (1654 – 1728): O barbaro Amore – Duetti da camera—Andréanne Brisson Paquin (soprano), Céline Ricci (mezzo-soprano), José Lemos (countertenor), Steven Soph (tenor), and Mischa Bouvier (baritone); Jennifer Morsches (cello), Deborah Fox (theorbo and guitar), and Jory Vinikour (harpsichord and direction) [Recorded in Sono Luminus Studios, Boyce, Virginia, USA, 14 – 18 February 2017; Musica Omnia mo0711; 1 CD, 66:07; Available from Musica Omnia, Naxos Direct, Amazon (UK), Amazon (USA), and major music retailers]

AGOSTINO STEFFANI (1654 – 1728): O barbaro Amore – Duetti da camera—Andréanne Brisson Paquin (soprano), Céline Ricci (mezzo-soprano), José Lemos (countertenor), Steven Soph (tenor), and Mischa Bouvier (baritone); Jennifer Morsches (cello), Deborah Fox (theorbo and guitar), and Jory Vinikour (harpsichord and direction) [Recorded in Sono Luminus Studios, Boyce, Virginia, USA, 14 – 18 February 2017; Musica Omnia mo0711; 1 CD, 66:07; Available from Musica Omnia, Naxos Direct, Amazon (UK), Amazon (USA), and major music retailers]

There is an uncannily timely lesson about cultural cooperation and coexistence to be learned from the fact that much of Twenty-First-Century observers’ acquaintance with the music of Italian composer Agostino Steffani is owed to the advocacy of a German-speaking aristocrat who became King of England. When the Elector of Hannover ascended to the English throne as George I in 1714, included in the souvenirs of his native land that accompanied him to London were Steffani scores that would otherwise now almost certainly be lost. Royal prerogative has indisputably sometimes been abused, but Sir Winston Churchill might reasonably have said of the fledgling Hannoverian dynasty’s preservation of Steffani’s work that there are few instances in musical history in which so much is owed to so few.

Born in 1654 in the Veneto region of Italy, near both Treviso and Venice, Steffani embarked upon his circuitous musical education at Venice’s Basilica di San Marco, where he served as a chorister. Noble patronage subsequently transported the young composer first to Munich, then to Rome, and ultimately back to the Bavarian capital, in which cities his natural abilities flourished under capable, nurturing tutelage. The path that led him to the court of the eventual George I also brought him into contact with a fellow composer who, unlike Steffani, would follow his employer to Britain: Georg Friedrich Händel. The extent to which Steffani may have influenced his Halle-born junior cannot be definitively discerned, but Händel undoubtedly benefited from the older man’s encouragement. Later appointments found Steffani in Brussels, Düsseldorf, and again in Hannover, where, like the esteemed castrato Farinelli, he was entrusted with diplomatic missions. It was whilst fulfilling political duties that the composer died in Frankfurt in 1728. Neglecting the work of an artist who was sufficiently esteemed by his superiors to be tasked with the handling of affairs of state seems anything but reasonable, but the whims of artistic fashion adhere to no conventional logic.

Recent years have ushered in a resurgence in Steffani’s reputation, propelled by the espousal of his music by renowned artists, perhaps the most committed amongst whom is mezzo-soprano Cecilia Bartoli. Productions of Steffani’s 1688 opera Niobe, regina di Tebe by London’s Royal Opera House and Boston Early Music Festival were recorded and released commercially to great acclaim, broadening awareness of his proficiency for writing for the stage. Appreciation of the keen understanding and innovative use of the prevalent music forms of his time that was likely the basis of his contemporaries’ respect for Steffani has been somewhat slower in expanding into the Twenty-First Century. Recorded with extraordinary acoustical clarity and immediacy by the industry-leading production team of Peter Watchorn (Executive Producer), Dan Merceruio (Producer), Daniel Shores (Engineer, Mixing, and Mastering), and Allison Noah (Recording Technician), O barbaro Amore, Musica Omnia’s recital of ten of Steffani’s sublime, stirring duetti da camera, offers a wonderful opportunity to examine the fluency of the composer’s musical language in the setting of inward discourses among voices and continuo instruments. Distant but undeniable relations of Monteverdi’s madrigals, the duets are here imaginatively ordered to form a continuous psychological arc that rivals the linear storytelling of Schubert’s Winterreise and Schumann’s Dichterliebe.

Amidst the bursts of enthusiastic rediscovery that have introduced Steffani and his work to modern audiences, his music has been revitalized by no artists more gifted than Deborah Fox, Jennifer Morsches, and Jory Vinikour. Directing these performances from the harpsichord, Vinikour paces each piece with masterful command of its musical and poetic nuances, both emphasizing the unique qualities of each duet and persuasively creating context within the cumulative narrative of the ten duets in succession. As a harpsichordist, Vinikour’s work has rarely been more refined, the restraint exhibited by his playing here affirming his faith in the expressive potential of the music. Avoiding the trap of excessive ornamentation, he fosters lean, lithe textures that support the vocalists rather than competing with them. Likewise, Fox plays theorbo and Baroque guitar with interpretive nimbleness that rivals her manual dexterity. Via her participation in performances of Baroque operas, she has honed an unerring instinct for aiding singers in maintaining conversational naturalness even in music of tremendous technical difficulty. Cadences are her punctuation, and Fox resolves phrases with unforced momentum. Morsches complements her colleagues’ efforts with alert, adaptive playing, accenting her tones in response to the words that they accompany. Fox’s theorbo and Morsches’s cello are an aural embodiment of Ovid’s Pyramus, and Vinikour’s harpsichord is the porous wall through which they converse with the singers’ Thisbe.

It seems unlikely that music of the quality heard on O barbaro Amore was written without the voices of specific singers resounding in Steffani’s mind, but the circumstances of the composition and first performances of these duets are largely unknown. Unanswered questions about their inception give the duets an alluring aura of mystery, but the performances on this disc establish beyond any uncertainty that soprano Andréanne Brisson Paquin, mezzo-soprano Céline Ricci, countertenor José Lemos, tenor Steven Soph, and baritone Mischa Bouvier are a quintet to whose talents any composer past, present, or future would delight in tailoring new music. The variety of Steffani’s deployment of different vocal registers in the duets is evidence both of the composer’s expertise in writing for voices and of the quality of the voices by which he anticipated his music being sung. Individually and in ensemble, the voices selected for this recording heighten the expressive impact of the duets with singing in which virtuosity, always present and wielded with confidence, seems an afterthought. Beauty of tone, purity of line, and honesty of emotional engagement are the characteristics that shape the artistic experience of O barbaro Amore. The raw sentiments of the words are felt before the difficulty of the music is perceived. How many performances of repertory of this vintage can truly be said to achieve this?

Brisson Paquin and Bouvier take the first steps on this journey with a traversal of ‘È spento l’ardore’ that establishes a charged atmosphere in which the relationships between text and music—and the alternating collaborations and confrontations between voices—conjure bitingly realistic tableaux of lovers’ rows and reconciliations. The brightly-polished patina of the soprano’s timbre soars above the darker hues of the baritone’s voice, but their sounds meld with surprisingly mellifluous homogeny. Brisson Paquin also shares an euphonious bond with Ricci, who joins her in an account of ‘Saldi marmi’ that closes the distance from Steffani’s music to duets for Rossini’s Semiramide and Arsace and Bellini’s Norma and Adalgisa. The adventurous harmonies of Diana’s exchanges with Endimione in Cavalli’s La Calisto also echo in Steffani’s music, rising to the surface in ‘Saldi marmi’ owing to the singers’ judicious management of the intervals that separate their vocal lines. Soph proves a wholly-qualified partner for Brisson Paquin, as well, delivering his part in their account of ‘Io voglio provar’ with dulcet but sonorous vocalism. In each of the first three duets, the soprano finds within her voice a range of colors that reflect the moods of the text, and each of her colleagues proves to be wonderfully skilled at revealing the unexpected modernity of Steffani’s word settings.

In the evocative strains of ‘Non so chi mi piagò,’ Brisson Paquin and Lemos fuse their voices into a stream of molten sound that illuminates the subtleties of the composer’s exploitation of the polarities of the upper and lower lines. The soprano’s vocalism is particularly effective here, her opalescent tones at the top of the stave cascading like lovers’ sighs. In the first of Ricci’s contests with Lemos, ‘Placidissime catene,’ the music seems to pour not solely from their lungs but from every cell of their bodies and every recess of their psyches. They unleash the latent verismo in Steffani’s music without one note of their performance straying from the appropriate style of elocution. This is historically-informed singing that refuses to be pedantic. Soprano and mezzo-soprano reunite for an affectingly spirited account of ‘Lontananza crudel’ in which their navigation of the intersections of their serpentine vocal lines compellingly limns lovers’ loathing of the distances that separate them.

The poignant potency of Ricci’s alliance with Brisson Paquin also courses through her performance of ‘Il mio seno è un mar di pene’ with Soph. The tenor voices his music with dramatic immediacy and silver-clad tone that gleams most brightly in his enunciation of vowels. The essence of the music is articulated in the lines ‘in sperar tropp’anelante solo si muor per essere costante,’ and the despair of these words permeates this reading of the duet. As in their first encounter on O barbaro Amore, there is an unique electricity that sizzles in Ricci’s and Lemos’s singing of ‘Quando ti stringo, o cara.’ Though similar in basic compass, their voices are very different instruments. The churning depths of the mezzo-soprano’s timbre collide with the lava that flows from the countertenor’s vocal cords, generating a scorching geyser of histrionic steam that lends their musical sparring an element of spontaneous but perceptively-wrought catharsis. The metamorphosis in Ricci’s demeanor in ‘Labri belli, dite un po’ is indicative of her submersion in the text, and she reacts alluringly to Bouvier’s vigorous but sensitive voicing of his music. Mezzo-soprano and baritone make of this duet a vibrantly hypnotic dance, approaching words and music with caressing sensuality.

The last chapter in this tale of love’s pains and pleasures, ‘Occhi, perché piangete,’ pairs Brisson Paquin with Lemos in a demonstration of artistry that epitomizes both the consistency of Steffani’s inspiration and the caliber of the music making that produced O barbaro Amore. These singers and the musicians who accompany them follow the music wherever it leads, swathing even the most uncomfortable niches of humanity in beauty. Above all, the performances on this disc raise a vital query: how can such music have been ignored for so many years?

Pat Benatar and the Four Aces got it right: love is truly both a battlefield and a many-splendored thing. History preserves few intimate details of Agostino Steffani’s life before his rise to prominence on Europe’s musical, political, and ecclesiastical stages, but his music provides glimpses of the man time has largely concealed. With the ten duetti da camera on this disc, Steffani transformed a remarkable aesthetic cognizance of the complexities of love into music of timeless cogency. In performing these duets, the artists whose work created O barbaro Amore unequivocally got it right, too.