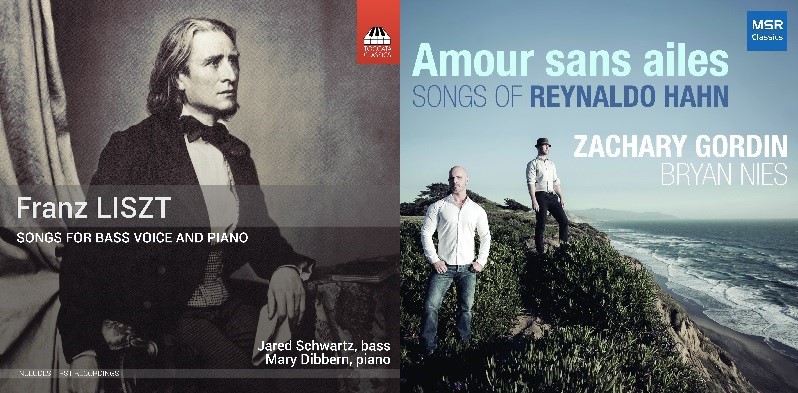

[1] FRANZ LISZT (1811 – 1886): Songs for Bass Voice and Piano—Jared Schwartz, bass; Mary Dibbern, piano [Recorded in St. Matthew’s Episcopal Cathedral, Dallas, Texas, 25 – 27 April 2017; Toccata Classics TOCC 0441; 1 CD, 68:07; Available from Toccata Classics, Naxos Direct, Amazon (USA), jpc (Germany), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

[1] FRANZ LISZT (1811 – 1886): Songs for Bass Voice and Piano—Jared Schwartz, bass; Mary Dibbern, piano [Recorded in St. Matthew’s Episcopal Cathedral, Dallas, Texas, 25 – 27 April 2017; Toccata Classics TOCC 0441; 1 CD, 68:07; Available from Toccata Classics, Naxos Direct, Amazon (USA), jpc (Germany), Presto Classical (UK), and major music retailers]

[2] REYNALDO HAHN (1874 – 1947): Amour sans ailes – Songs of Reynaldo Hahn—Zachary Gordin, baritone; Bryan Nies, piano [Recorded in Schroeder Hall, Green Music Center, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, California, USA, 8 – 9 October 2016; MSR Classics MS 1649; 1 CD, 46:06; Available from MSR Classics, Amazon (USA), and major music retailers]

The celebrated soprano Alma Gluck (1884 – 1938) once said that ‘the sincerity of the art worker must permeate the song as naturally as the green leaves break through the dead branches in springtime.’ Gluck was a daughter of cultural climates very different from those of the Twenty-First Century, but how remarkable it is to find her referring to herself and her counterparts not as singers, musicians, interpreters, or artists but as art workers! Perceptions of a successful musician’s life are often warped by fantasies of flitting from continent to continent in first class, sipping champagne of exalted vintage, and performing with the aura of a deus ex machina descended in order to rescue audiences from their own barbarism. Lives such as this are now as rare as handwritten letters and true privacy, and what remains is the difficult, sometimes disheartening work of preserving niches for the cultivation and enjoyment of art amidst the confusion of modern living.

Both the viability and the validity of the musical forms that the heroes of the Twentieth Century safeguarded through two World Wars depend upon the diligence of the art workers to whom Gluck appealed, and never is any winter of discontent endured by those who love song except by clinging to the hope for the emergence of voices that bring vernal renewal—voices like those heard on two of 2017’s most captivating recordings. Toccata Classics’ disc of songs by Franz Liszt performed by bass Jared Schwartz and pianist Mary Dibbern and MSR Classics’ homage to the songs of Reynaldo Hahn featuring baritone Zachary Gordin and pianist Bryan Nies are wondrously verdant bursts of life in a cultural winter that seems destined to be destructively long-lived.

The lives of few composers in the history of Western Classical music have been as eventful as that of Franz Liszt. Born in 1811 in the Hungarian town of Doborján, known since the end of World War I as the Austrian hamlet of Raiding, Liszt was the son of an accomplished musician who was a colleague of Joseph Haydn in service to the Esterházy family. Encountering Salieri, Beethoven, and Schubert during his first fifteen years of life, the young Liszt inaugurated a lifelong series of seminal musical acquaintances encompassing a panoply of composers as diverse as Berlioz, Chopin, and Saint-Saëns that would eventually culminate in his daughter Cosima marrying Richard Wagner. In a long career often touched by personal tragedy, Liszt witnessed virtually the whole evolution of Nineteenth-Century Romanticism, both advocating for its development using his wide-ranging influence and advancing its progress with his own compositions.

For listeners whose familiarity with Liszt’s music is defined by the brazen, sometimes bombastic virtuosity of works like his Hungarian Rhapsodies and Piano Concerti, the many delicate qualities of his Lieder may be surprising. Indeed, the fact that Liszt composed songs at all is seldom considered in assessments of his artistry. [Beautiful recordings of Liszt Lieder by sopranos Hildegard Behrens and Dame Margaret Price regrettably seem to be known far less widely than they deserve to be.] Fusing elements of the styles to which he was exposed in Vienna during his youth and in Paris, to which metropolis he relocated soon after the death of his father in 1827, Liszt was a masterful composer of songs, as the performances on this insightfully-arranged Toccata Classics disc affirm. There are in these songs moments of the exhilarating musical exhibition expected of the composer’s work, but far more abundant are unexpected subtleties of musical invention and response to text. History does not portray Liszt as a man of Chopinesque sensitivity, but the portrait conjured by his songs and these performances of them depict an artist of wit, intellectual profundity, and keen understanding of humanity.

All of the Lieder included in their unmistakably affectionate survey of Liszt’s songs are here sung by a bass voice for the first time on disc, but this is also the world-première recording of the song with which Schwartz and Dibbern launch the disc, ‘Weimars Volkslied.’ A circa 1853 setting of a text by Peter Cornelius, the song wields an unaffected sophistication that belies its ‘Volkslied’ title and recalls the work of the Mendelssohn siblings, Fanny and Felix. Singer and pianist revel in the song’s emphatic style, Dibbern playing the fanfare-like figurations with the exuberance of bells tolling on a civic holiday. This contrasts markedly with Schwartz’s smooth singing of the song’s lyrical interludes.

First composed in 1843 – 1844 and revised in 1864, the earlier version of ‘Pace non trovo’ from the Tre sonetti di Petrarca is frequently included in recitals by lyric tenors, who cherish its ascents to D♭5, but its demands are no less daunting—and its rewards no less plentiful—in the later transposition for lower voice. The performance that the song receives from Schwartz and Dibbern makes a very strong case for the version for bass, this bass’s singing evoking the authentic voice of the poet with the inherent dignity of his delivery. Respectively using words by Ferdinand von Saar and Alfred de Musset, ‘Des Tages laute Stimmen schweigen’ from 1880 and ‘J’ai perdu ma force et ma vie’ from 1872 are very different pieces that here benefit from the same virtues of expertly-managed singing and unfailingly communicative pianism. In each of the songs on this disc, in fact, Dibbern gets at the heart of the music’s ethos, providing Schwartz—and Liszt and the poets, as well—not with accompaniment but with a true partner in conversation.

Likely one of the earliest songs presented on this disc, ‘Jeanne d’Arc au bûcher’ is a visceral, almost operatic adaptation of words by Alexandre Dumas père in which Liszt rivals the dramatic storytelling of Verdi’s Giovanna d’Arco and Tchaikovsky’s Orleanskaya deva on a considerably smaller scale. Schwartz sings the piece superbly, articulating the text with great attention to the emotional depth of Dumas’s diction. Dibbern’s performance dazzles, too, the anxious pounding of the heroine’s heart, the doubts, the fears, and the pangs of patriotism echoing in her playing, not supporting the words but instigating them.

Aside from ‘Über allen Gipfeln ist Ruh,’ an 1849 setting of a text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and an elegant employment of words by Heinrich Heine in ‘Du bist wie eine Blume,’ both lucidly performed here, several of the finest songs on this disc use texts by poets whose names are unlikely to be known by listeners whose first languages are not French or German. The words of ‘Sei still’ are the work of Adelheid von Schorn, and they inspired Liszt to writing of striking starkness that is chillingly conveyed by Schwartz’s dusky but dulcet lower register. The resonance of the bass’s bottom octave is also an important component of the panache of his performance of ‘Le Juif errant,’ in which Pierre-Jean de Béranger’s words are handled by composer and pianist with finesse. Schwartz and Dibbern react to the song’s emotional gradations with uncompromising directness—the only effective approach to this piece. Ferdinand Freiligrath penned the words that sparked Liszt’s creativity in ‘O lieb, solang du lieben kannst!’, and the music is widely known even if the poet and his work are not. Its ebullient melody borrowed from the third of the composer’s much-played Liebesträume for solo piano, this is surely Liszt’s best-known song, but Schwartz and Dibbern perform it as though it has never been heard before, their shared musicality triumphing over the hint of lugubriousness that results from assigning the song to a bass voice.

If the poetry of Alfred, Lord Tennyson seems an unlikely source of material for Liszt, the many felicities of the composer’s 1879 treatment of ‘Go not, happy day’ reminds the listener that appearances are deceiving. There are passages in this song in which distant kinship with Gerald Finzi’s vocal writing is apparent, but the linguistic fluidity of Liszt’s word setting is as compelling in English as in languages with which he was more acquainted. The Indiana-born Schwartz sings English with particular clearness, giving vowels and consonants equal weight, and the transparency with which both he and Dibbern perform the music is deeply affecting. The author of many texts set to music by his friend Franz Schubert, Franz von Schober also served as literary stimulus for Liszt’s 1849 ‘Weimars Toten,’ commissioned to mark the centennial of Goethe’s birth. Schwartz and Dibbern create an aptly commemorative atmosphere, immersing themselves in Liszt’s striking musical homage to the great poet and the city in which he died. Already a musical relationship of uncommon congruity in their Toccata Classics recording of mélodies by Ange Flégier, the partnership between bass and pianist is here refined to an even more admirable class of artistic expression. On this disc, their music making is as Liszt’s must have been when he sat at the piano in Rome’s Villa Medici in 1886, surrounded by Claude Debussy, Victor Herbert, and Paul Vidal: shorn of all extravagance and ego, these are performances by and for friends.

If the hallmark of effective Lieder is a consistent profusion of distinguished melodies whereby the listener experiences words on a level that transcends conversational comprehension, the songs of Franz Liszt recorded by Jared Schwartz and Mary Dibbern are exceptionally persuasive representatives of their genre. Liszt’s undervalued mastery of the composition of Lieder notwithstanding, any music performed with the passion heard on this disc would earn appreciation. Here, at last, is a recording of Lieder for bass worthy of comparison with Kurt Moll’s and Cord Garben’s magnificent Orfeo recital of Schubert Lieder.

![]()

As captivating and inexplicably overlooked by musicians capable of performing them idiomatically as the Liszt songs recorded by Jared Schwartz and Mary Dibben, the lusciously lyrical mélodies of Reynaldo Hahn are not unknown to connoisseurs, especially those with interest in the music of fin-du-siècle Parisian salons, in which Hahn’s music was immensely popular. When the gorgeous melodic lines of Hahn’s songs caress the ears, however, it is virtually impossible not to wonder why such music is not performed as frequently as the ubiquitous Italian canzonette that litter singers’ repertoires. In the seven decades since Hahn’s death in 1947, perhaps something crucial has been lost in musical translation. This MSR Classics release, recorded by Swineshead Productions engineer David v.R. Bowles with the ambient clarity that the music requires, restores Hahn’s songs their rightful place alongside the works of Henri Duparc, Gabriel Fauré, Édith Piaf, and Charles Aznavour as a pillar of French chanson.

Though their milieux were very different, there are many parallels in the circumstances of Hahn’s and Liszt’s formative years. Born in the Venezuelan capital, Caracas, in 1874, Hahn was the child of an affluent family with strong ties to Europe, bonds which sustained the family’s prosperity when they were forced to seek refuge from the political volatility that ravaged Venezuela in 1877. As Liszt had done after the death of his father a half-century earlier, Hahn found a new home in Paris, where the vibrant musical scene bewitched his imagination and whetted his appetite for composition. Admitted at the age of ten to the Conservatoire de Paris, by which institution the similarly-aged Liszt was denied tuition, Hahn studied with Gounod, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns, absorbing their music with a seemingly boundless curiosity. Throughout his career, he was an avid consumer of Paris’s operatic offerings, maintaining a presence at the Opéra as noteworthy as that of Gaston Leroux’s phantom. Beyond his gift for creating haunting melodies, there was nothing spectral about Hahn’s talent, however. Unlike Liszt’s Lieder, the best-known of which are overshadowed in modern awareness by his orchestral and piano music, Hahn’s songs form the nucleus of their composer’s renown. Even so, hearing them sung outside of France is a rare gift.

Like their colleagues’ performances of Liszt’s songs, Gordin and Nies bring to their traversals of the twenty-one songs on Amour sans ailes an artistic alliance of near-perfect symbiosis. Recalling the gist of Algernon’s remark in Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest that ‘women only call each other sister when they have called each other a lot of other things first,’ it is intimated in the disc’s liner notes that the camaraderie between Gordin and Nies was not fostered without hindrance, but sorting out differences has in their case facilitated an uninfringeable sense of purpose that is audible in the first bars of their urgent but unexaggerated performance of the Victor Hugo setting ‘Réverie.’ In this and all of the selections on the disc, Gordin sounds like an exemplar of a Fach long thought to be extinct: the uniquely French baryton-Martin. Uniting a plush lower octave, smooth navigation of the passaggio, and well-supported falsetto, the baritone sings this music as though he composed the songs himself, projecting a sense of spontaneity even when meticulous care governs his phrasing.

The texts of Hahn’s Chansons grises are the work of Paul Verlaine, whose ambiguous imagery finds in Nies’s playing a stage upon which to act out its cunning dramas. In the lovely ‘Chanson d’automne,’ the singer’s enunciation of the poet’s words is amplified by the pianist’s understated intensity. In ‘Tous deux,’ too, Nies enhances the interpretive impact of Gordin’s singing by playing as though the vocal line were an extension of the piano part. Gordin voices ‘L’Allée est sans fin...’ and ‘En Sourdine’ with close attention to their shifting moods, and his reading of the sublime ‘L’heure exquise’ is lofted upon a current of diaphanous expressivity propelled by Nies’s rhythmic sharpness. The impact of ‘Paysage triste’ is heightened by both singer and pianist approaching the piece without so much as a hint of preciosity, allowing words and music to reach the listener uninhibitedly. ‘La bonne chanson’ is just that: an undeniably well-crafted song. The performance that it receives from Gordin and Nies wholly justifies the title. Hahn returned to Verlaine’s poetry in ‘L’incrédule’ and ‘Fêtes galantes,’ songs with little in common except for the poet’s words and the composer’s sagacious uses of them, and Gordin sings them with flawless cognition of their singular characters and seductive tone.

The expressivity of Alphonse Daudet’s words in ‘Trois jours de vendange’ is realized by Gordin with expertly-judged emphasis echoed in Nies’s rendering of the piano’s side of the dialogue. Similarly, the nuances of Charles Marie René Leconte de Lisle’s texts in Études latines are engagingly explored without ever being over-accentuated. Gordin voices ‘Lydé’ with seductive charm, and his account of ‘Pholoé’ scintillates, the voice cascading through the soundscapes created by the piano. The related spirits of ‘Nocturne’ and ‘Dans la nuit,’ settings of texts by Jean Lahor and Jean Moréas, are enlivened by Gordin’s earnest singing, and his moving performance of Hahn’s adaptation of Augustine-Malvina Blanchecotte’s ‘La chère blessure’ grows from the fertile soil of Nies’s emotive playing.

Like Liszt’s setting of Tennyson, Hahn’s uses of Mary Robinson’s verses in Love without wings displays an affinity for recognizing and tapping the innate musical potential of English words—a trait lacked by many native English-speaking composers. A gentle wistfulness permeates Gordin’s singing of ‘Ah! Could I clasp thee in mine arms,’ and the serene resignation with which he voices ‘The fallen oak’ transitions to ambivalent playfulness in ‘I know you love me not,’ all animated by vocalism of exquisite control. The collaboration between voice and piano is nowhere more efficacious than in Gordin’s and Nies’s performance of ‘L’énamourée,’ their joint commitment to the music reaching into the shadows of Théodore de Banville’s text. Composed in 1913, ‘À Chloris,’ a setting of verses by Théophile de Viau, is perhaps the most familiar of Hahn’s songs, but its familiarity breeds no contempt in Gordin’s and Nies’s presentation. Rather, the pianist plays with the vigor of first discovery, and the baritone’s chic singing triggers memories of Gérard Souzay. Above all, though, Gordin recognizes that this is not music that should be whimpered or whined: whilst listening to this disc, one is unlikely to ever feel compelled, as one sometimes does when hearing Souzay performances, to exclaim, ‘Just sing, s’il vous plaît!’ Simply singing—which is not to be confused with singing simply—is what Gordin does best.

Respect is in some instances the cruelest manifestation of damning with faint praise. Respect is too often misused in musical societies as an excuse for inattention and ignorance. The casual listener professes to respect a composer’s or a musician’s artistry and leaves it at that: if one expresses an all-encompassing respect, is it really necessary to actually know an artist’s work and its context? One of the many victories of this pair of discs is answering that question with irrefutable evidence of the folly of dismissing insufficiently-remembered music with respectful disinterest. Like Alma Gluck, Jared Schwartz, Zachary Gordin, Mary Dibbern, and Bryan Nies clearly realize that the art worker’s toil never ends. Were she able to hear the performances of songs by Franz Liszt and Reynaldo Hahn on these discs, Gluck would undoubtedly congratulate this quartet of art workers on jobs done exceptionally well.