Christopher Marlowe wrote that Helen of Troy possessed the ‘face that launched a thousand ships,’ her beauty having been the catalyst in the collision of egos and empires that precipitated the Trojan War. Had she been a singer, as she became in Arrigo Boito’s Mefistofele, how much more contentious quarrels about her virtues might have been! Disputes among today’s Classical singing enthusiasts are sometimes fueled by lessening comprehension of basic vocal attributes and historical precedents. As in many aspects of modern life, a quest for absolutes frequently results in mischaracterizations. A soprano who sings fiorature correctly is not necessarily a coloratura soprano, for instance, and categorizing the voice based upon a single ability rather than its many qualities, no matter how admiringly, disserves the singer.

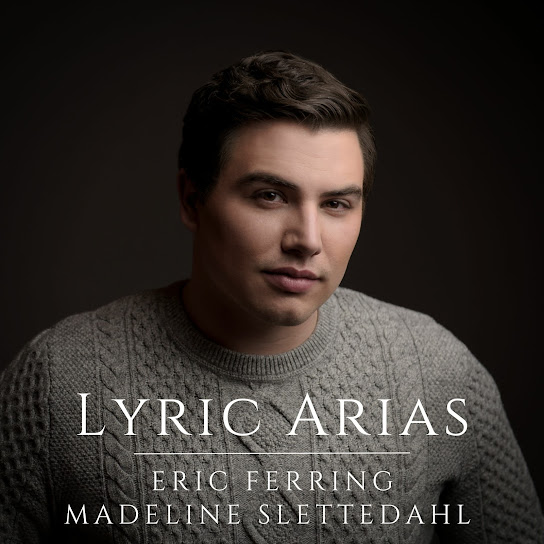

Recorded in the Chicago studios of WFMT under the supervision of acclaimed audio engineer Chris Willis, whose expertise yielded sonic ambience that, whether heard through headphones or speakers, replicates the acoustic of an intimate performance space, tenor Eric Ferring’s Lyric Arias is a mellifluous recital of selections from three centuries, performed by the sort of voice for which they were written. Captured without multitudes of takes and the goal of release to the public as a collection, these performances are splendid exhibitions of an artist at work, his concentration on stylistic correctness engendering musical and textual accuracy. Lyric arias can be successfully sung by many different voices, but Ferring demonstrates that, just as singers should be judged primarily by how rather than by what they sing, music is defined by how it was written, not by who sings it.

Ferring sagaciously begins his survey of the development of writing for the tenor voice with performances of two numbers popularized in the Eighteenth Century by John Beard, the singer for whom Georg Friedrich Händel composed some of his finest music for tenor. Comparing Händel’s writing for Beard with tenor parts in operas, madrigals, and sacred works by Monteverdi, Cavalli, and other Seventeenth-Century composers suggests that Beard was among the earliest lyric tenors of the type still heard today. Beard was not the tenor soloist in the first performance of Händel’s Messiah (HWV 56) in Dublin in 1742, but the oratorio’s first performances in London in the following year benefited from Beard’s participation.

It is difficult to imagine even Händel’s preferred tenor singing the recitative ‘Comfort ye, my people’ and air ‘Ev’ry valley shall be exalted’ more affectingly than Ferring sings them on this release. With true bel canto technique harkening back to the teachings of Manuel García, Ferring supports tones with breath control that facilitates consistent evenness throughout the upper and lower registers, the passaggio navigated with laryngeal placement that is ideal for the voice. Unlike many native speakers of English, Ferring enunciates the language clearly, the words crisp but avoiding overwrought elocution. His voicing of ‘Comfort ye’ imparts an apt sense of anticipation, and his account of ‘Ev’ry valley,’ its divisions articulated with attention to their relationship with the text, accentuates the ingenuity with which Händel used music as a vital element of his storytelling.

Eight years before singing Messiah in London, Beard portrayed the title character’s brother Lurcanio in the 1735 Covent Garden première of Händel’s opera Ariodante (HWV 33). Ferring furthers his tribute to Beard with his galant but elegant account of the aria ‘Il tuo sangue, ed il tuo zelo.’ The caliber of the tenor’s Italian diction rivals that of his English. The greater difficulty of Lurcanio’s fiorature and the Italian vowels challenge Ferring’s vocal dexterity, but he intuitively uses the rhythmic precision of pianist Madeline Slettedahl’s playing as the foundation upon which he creates an exhilarating account of the piece. Moreover, he sings with unfailing musicality and restraint in ornamentation.

Commissioned in 1845 by the Birmingham Festival to pay homage to the legacies of Händel and Haydn with a work of his own, Felix Mendelssohn gifted the oratorio-loving British public with his Opus 70, Elijah, a score with much in common, structurally, with Händel’s Saul. In addition to being greatly respected by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, the tenor engaged for the first performance of Elijah in Birmingham Town Hall on 26 August 1846, Berkshire native Charles Lockey, so moved Mendelssohn with his singing of the aria ‘Then shall the righteous shine forth’ that the composer wrote of struggling to contain his emotions. Ferring’s voicing of the aria elicits a similar response, Mendelssohn’s ascending vocal line molded with grace and extraordinary tonal beauty. Ferrig’s incandescent top A♭s are the expressive summits of the performance, the reverence of the text resounding in the voice.

In the operas composed during the first half of his career, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote tenor rôles that embodied the style of bravura singing synthesized from Händel’s models by composers like Niccolò Jommelli, Giovanni Sarti, and Tommaso Traetta, a tradition to which Mozart returned in large part in his final Italian opera, La clemenza di Tito. In his progressive Singspiele Die Entführung aus dem Serail and Die Zauberflöte, as well as in Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte, however, Mozart advanced the art of devising music for tenor protagonists along the path that led to bel canto.

Fascinatingly, Mozart’s first Tito Vespasiano in La clemenza di Tito, a closer relative of the name parts in Idomeneo, rè di Creta and Mitridate, rè di Ponto than of Entführung’s Belmonte and Zauberflöte’s Tamino, was Antonio Baglioni, who had earlier originated the rôle of Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni. The aria written for him in Don Giovanni, ‘Il mio tesoro intanto,’ indicates that Baglioni wielded both vocal nimbleness and exceptional management of breath. With his traversal of ‘Il mio tesoro,’ Ferring affirms that he is a worthy successor of Baglioni, delivering the coloratura passages with an appealing lightness of approach mirrored by Slettedahl’s fleet handling of the aria’s musical progression.

Vincenzo Calvesi, the singer for whom Mozart tailored his music for Ferrando in Così fan tutte, was renowned in Habsburg Vienna as an interpreter of tenor rôles in the operas of Antonio Salieri, whose compositional style encompassed late-Baroque excesses and Gluckian sparsity. Ferrando’s arias in Così fan tutte can be said to manifest similar ambiguity. ‘Ah! lo veggio quell’anima bella’—until recent years often omitted from performances and recordings of the opera—is dazzlingly virtuosic, but ‘Un’aura amorosa,’ while making its own daunting technical demands, enthralls with its expansive, plaintive lines and serenity. Ferring sings ‘Un’aura amorosa’ hypnotically, the voice as firm and focused at the bottom of the range as it is glistening at the top. Here, too, the effectiveness of the tenor’s efforts is heightened by his close collaboration with the pianist, whose phrasing provides poetry and propulsion.

Before leaving the stage and focusing on pedagogy, Manuel García enjoyed a fruitful collaboration with Gioachino Rossini, one of the best-known products of which was his creation of the rôle of Conte d’Almaviva in Il barbiere di Siviglia in 1816. Almaviva’s cavatina in Act One, ‘Ecco ridente in cielo.’ was unquestionably fashioned to capitalize on García’s unique gifts, but the music is also a fine vehicle for Ferring’s vocal and theatrical magnetism. His fiorature, intonation, and top A, B, and C are all stellar, but it is the youthful exuberance of his performance that gives this ‘Ecco ridente in cielo’ its bewitching charm. This is the song of a wily aristocrat whose pursuit of amorous adventure does not impel him to take himself too seriously.

Ferring’s performance of the much-loved ‘Rêve’ from Act Two remindsTwenty-First-Century listeners that Chevalier des Grieux in Jules Massenet’s Manon was also memorably sung, albeit in German, by Slovene tenor Anton Dermota, one of the Twentieth Century’s most accomplished Mozart singers. Ferring shares Dermota’s innate and commendably adaptive command of style, transitioning from the poise of his singing of Mozart’s music to Massenet’s more effusive, emotive musical idiom. Ferring also refines his linguistic skills to encompass shaping of French text that lends his utterance of ‘C’est vrai! ma tête est folle’ stirring sincerity. The wonderment audible in his singing of ‘Instant charmant où la crainte fait trève’ touchingly evinces the mood conjured by the words. The Francophone authenticity of this performance of ‘En fermant les yeux je vois’ is validated by Ferring’s ravishing voix mixte top A, the aural embodiment of des Grieux’s humble but euphoric vision of his life with Manon.

In the 1951 world première of Igor Stravinsky’s operatic treatment of situations taken from the eight images of William Hogarth’s iconic The Rake’s Progress, the eponymous rake was sung by American tenor Robert Rounseville, a singer now remembered more for his work in cinema and musical theater than for his operatic portrayals. Eighteen months after the opera’s first performance in Venice, the Metropolitan Opera staged the work with Eugene Conley as Tom Rakewell. In this recorded performance of Tom’s Act One aria ‘Here I stand,’ it is another MET Rakewell, Paul Groves, whose Ferring’s singing recalls. The character’s trademark self-assurance is palpable in this ardent, utterly secure traversal of the music. Even in the context of a studio recording, Ferring vividly acts through the voice. In the opera, Tom’s exclamation of ‘I wish I had money!’ has the fateful consequence of summoning the malevolent Nick Shadow: here, it delights without peril.

There is no greater pleasure for voice aficionados than hearing a voice of high quality, bolstered by proper technique, singing music to which it is suited. This is the abidng pleasure of Eric Ferring’s performances of these lyric arias, in which a young artist invites the listener to experience the music from a singer’s perspective with immediacy that can rarely be achieved in recital halls.