![ARTS IN ACTION: Italian composer GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792 - 1868), whose 1822 opera ZELMIRA will be performed in concert by Washington Concert Opera on Friday, 5 April 2019 [Image from a Nineteenth-Centry engraving] ARTS IN ACTION: Italian composer GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792 - 1868), whose 1822 opera ZELMIRA will be performed in concert by Washington Concert Opera on Friday, 5 April 2019 [Image from a Nineteenth-Centry engraving]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhBLbHXzAShF_Y6Muhkt5bmrrgmZYe5PX6U1fJ-K-JGJHNXN9jqWNCmmfX7xfqpV85NmMZwn_P_de_OvKNlSMZ_tSGLv8Zgl7hcGoL0EPURRPePX1G38sYHx2eUz8j5C8sebKzLQezFksM/s280/Gioachino-Rossini.jpg)

Gioachino Rossini was two weeks from his thirtieth birthday when his opera Zelmira premièred in Naples on 16 February 1822—and, though he would live for another forty-six years, only seven years from retiring from the composition of opera. From the first performance of the one-act farce La cambiale di matrimonio in 1810 until the 1829 première of Guillaume Tell, Rossini’s music dominated opera, not least in Naples. Beginning with Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra in 1815, ten of Rossini’s operas débuted in Naples, all of them serious operas rather than the comedies that have sustained Rossini’s popularity unto the Twenty-First Century. Did Neapolitan audiences lack a sense of humor, or did they perceive in Rossini’s music qualities more profound than the affable hilarity that endeared the son of Pesaro to all of Europe?

Rossini’s operas are rarely praised for the literary integrity of their libretti, but the composer often found inspiration in the work of eminent writers: Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais in Il barbiere di Siviglia, Jean Racine in Ermione, Sir Walter Scott in La donna del lago, and Friedrich von Schiller in Guillaume Tell, for instance. The texts of Ermione and La donna del lago were written by the appointed poet of the royally-supported Neapolitan opera houses, Andrea Leone Tottola, who turned to a 1762 play by Pierre-Laurent Buirette de Belloy for the source of Zelmira’s plot. [Tottola later adapted de Belloy’s 1777 drama Gabrielle de Vergy for an operatic setting by Gaetano Donizetti. De Belloy’s 1765 patriotic epic Le siège de Calais was also a source for Salvadore Cammarano’s libretto for Donizetti’s L’assedio di Calais.] Though not as familiar to Twenty-First-Century readers as Racine’s Andromaque and Scott’s The Lady of the Lake, de Belloy’s Zelmire provided Rossini with a tale of political intrigue, false accusations, and tested loyalties that he recounted with music that both embodies and in some scenes defies the genial tunefulness for which his operas are renowned.

Two months after its Neapolitan première, Zelmira was staged in Vienna, where the score provoked heated debate about the Teutonic elements perceived by some listeners, likening it to music by Gluck and Mozart. Thereafter, the opera was performed throughout Italy; in London, where Rossini conducted the inaugural British performance; in Paris and Lisbon; and in opera-loving New Orleans. Zelmira’s good fortune waned as the Nineteenth Century drew to its close, joining Rossini’s serious operas in being eclipsed by their comic siblings and the operas of Giuseppe Verdi. Zelmira returned to Naples in 1965 in a production that featured Romanian soprano Virginia Zeani in the title rôle, but reappraisal of the opera’s considerable merits has been slow. A 1988 concert performance in Venice gave rise to a studio recording and a staged production in Rome, all with Cecilia Gasdia as Zelmira. Mariella Devia sang the eponymous heroine in Pesaro, Lyon, and Paris, and the opera was performed at the Edinburgh Festival in 2003 and reprised at Pesaro in 2009. Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Zelmira on 5 April 2019, likely the first performance of the opera in America since its New Orleans début in the 1830s, offers a rare opportunity to hear this music sung by a cast capable of recreating the vocal flair that enchanted Naples 197 years ago.

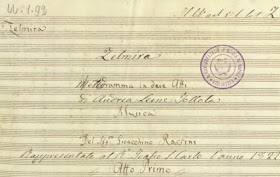

From Naples, with love: the title page of the autograph manuscript of Gioachino Rossini’s Zelmira, being performed by Washington Concert Opera on 5 April 2019

From Naples, with love: the title page of the autograph manuscript of Gioachino Rossini’s Zelmira, being performed by Washington Concert Opera on 5 April 2019

Australian conductor Antony Walker has been a tireless champion of underappreciated repertoire in his capacity as Washington Concert Opera’s Artistic Director, and his trademark enthusiasm pervades his contemplation of resurrecting Zelmira. Above all, Walker is exhilarated by the idiosyncrasies that enliven this score. ‘Zelmira has a few unique touches that really spring out dramatically,’ the Maestro mused. ‘One such surprise is at the very beginning of the opera, where Rossini chooses to dispense with the traditional overture and launch straight into a chorus scene where we discover that Prince Azor has been murdered.’ The convoluted conceits of Tottola’s libretto have received much criticism, but Walker trusts Rossini’s dramatic instincts to make Zelmira viable for today’s listeners. ‘The opera starts with shuddering strings and menacing wind/brass diminished chords that plunge the audience into a world of uncertainty and chaos. Antenore then enters and feigns horror and outrage at this murder—he basically engineered it, with the help of Leucippo. Rossini provides firstly flowery, ironic music, then a mock-heroic cabaletta underscoring the insincerity of the usurper.’

Luring the audience into the opera’s conspiratory atmosphere, Rossini heightens the impact of the characters’ conflicts with chameleonic music, one moment’s delicate tenderness giving way to another’s rousing bravura display. ‘A surprise of a very different quality is the exquisite duettino for Zelmira and Emma, depicting Zelmira’s sorrow in having to hand over her small son to Emma’s protection for the foreseeable future, as she knows that Antenore and Leucippo are closing in on her and will soon probably deprive her of her liberty,’ Walker asserted. ‘This duettino is perfectly and breathtakingly scored for only a quartet: the two singers, English horn, and harp, and [it] is a delicate, poignant, and moving jewel of chamber music, beautifully positioned just before the aggressive and frenetic finale to Act One.’ This musical variety is Zelmira’s foremost strength, Walker feels, but it also begets some of the score’s greatest challenges.

Creating and maintaining dramatic momentum are hallmarks of Walker’s conducting, and he is acutely aware of the conductor’s integral rôle in the success of a performance of Zelmira. His method of pacing Washington Concert Opera’s Zelmira will be guided by five principals. ‘The biggest issues in keeping a work of such length riveting in performance are: (1) to equally take care of the large dramatic arcs in each act, as well as the small details on each page of the score; (2) [to] make sure that individual characters are very specifically drawn and presented; (3) [to] always remember to keep the recitatives dramatically engaging and full of emotional and dramatic contrast; (4) [to] ensure that the orchestra is always adding specifically to the drama, encouraging the players [to] feel like characters and helping them express the underlying emotions of each scene; and (5) [to] make sure [to make the most of] each special and unique moment in the score,’ he explained. These are lofty goals, but Walker has devoted his career to meeting the musical and dramatic needs of pieces that other conductors ignore.

Performing Zelmira in concert allows the artists and the audience to wholly surrender themselves to the music, but Walker realizes that the ultimate impression made by the performance relies upon satisfying musical storytelling. ‘For a work like Zelmira, which is not well known and which most of the principals are singing for the first time, I like [to] at first sit together and discuss the characters; how they feel about their characters and how I see their characters in the whole scheme of the drama,’ he said. ‘It is especially important in concert for singers to understand the characters of their colleagues, as we don’t have staging rehearsals to take us through this important step of understanding, exploration, and discovery.’

![ARTS IN ACTION: American tenor LAWRENCE BROWNLEE, who will sing Ilo in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's ZELMIRA on 5 April 2019, as Rinaldo in ARMIDA at The Metropolitan Opera in 2010 [Photograph by Ken Howard, © by The Metropolitan Opera] ARTS IN ACTION: American tenor LAWRENCE BROWNLEE, who will sing Ilo in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's ZELMIRA on 5 April 2019, as Rinaldo in ARMIDA at The Metropolitan Opera in 2010 [Photograph by Ken Howard, © by The Metropolitan Opera]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEju-eerYzqQgFiKJxeeu18Qrj7ZjqsvzMbRHEH1Uee1Vr0A8PxXSAhJh8OKqbnvOfdNmD4O8XlqsOXDF7MdXU2U47ailTMRpOJ0reahTy5UgdjcaaWCeFP9QqbqTfwwdIAGTwnYtWIH9Yo/s280/Lawrence-Brownlee_Rinaldo-ARMIDA_MET_2010_Ken-Howard.jpg) Coloratura champion: American tenor Lawrence Brownlee, who will sing Ilo in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Zelmira on 5 April 2019, as Rinaldo in Armida at The Metropolitan Opera in 2010

Coloratura champion: American tenor Lawrence Brownlee, who will sing Ilo in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Zelmira on 5 April 2019, as Rinaldo in Armida at The Metropolitan Opera in 2010

[Photograph by Ken Howard, © by The Metropolitan Opera]

To date, Ohio-born tenor Lawrence Brownlee’s Rossini portrayals at New York’s Metropolitan Opera include Conte d’Almaviva in Il barbiere di Siviglia, Don Ramiro in La Cenerentola, Rinaldo in Armida, and Giacomo in La donna del lago. One of the most acclaimed modern exponents of music written by Rossini for Giovanni David, who created the rôle of the Trojan prince Ilo in Zelmira, Brownlee returns to Washington Concert Opera for his rôle début as Ilo, bringing to the performance a battle-tested strategy for conquering Rossini’s daunting vocal salvos. ‘Ilo’s entrance aria “Terra amica” calls for a virtuosic voice to sing it in order to be done well,’ the tenor stated. ‘It sits very high and is very demanding, but it's also very gratifying if you can equip yourself to do it well.’ Equipping oneself to sing the aria well is a Herculean task, he admitted. ‘Just getting through it is an accomplishment!’ Brownlee confided with characteristic wit. Though Ilo is new to his repertory, he is well acquainted with ‘Terra amica,’ which was included on his Delos recording of Rossini virtuoso arias. ‘I always aim to not only get through the demanding virtuosity of it, but to focus on the beauty of the writing and sing it musically and with intention,’ Brownlee reflected. ‘That is the thing that sets [the aria] apart and makes it a moment in the opera that’s not to be missed. I hope the Washington audience will enjoy it!’

![ARTS IN ACTION: Spanish mezzo-soprano SILVIA TRO SANTAFÉ, who will sing the title rôle in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's ZELMIRA on 5 April 2019, as Rosina in IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA at San Diego Opera in 2012 [Photograph by Ken Howard © by San Diego Opera] ARTS IN ACTION: Spanish mezzo-soprano SILVIA TRO SANTAFÉ, who will sing the title rôle in Washington Concert Opera's performance of Gioachino Rossini's ZELMIRA on 5 April 2019, as Rosina in IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA at San Diego Opera in 2012 [Photograph by Ken Howard © by San Diego Opera]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjqJFbZhqel3wWSDnb4CXTTcX-32jNtX3Hs5-KlDLLvz22pqsoUhLJrbaRmUhZt8A6jT44hcMaN2B36JNyRI0-WoxlkolbwCr5Q9O7myRWa_nk1vKII2Sb_6CFSZMOZm-fvYE55bPZ80iY/s280/Silvia-Tro-Santafe_Rosina_BARBIERE_San-Diego_2012_Ken-Howard.jpg) Voz de Valencia: Spanish mezzo-soprano Silvia Tro Santafé, who will sing the title rôle in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Zelmira on 5 April 2019, as Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia at San Diego Opera in 2012

Voz de Valencia: Spanish mezzo-soprano Silvia Tro Santafé, who will sing the title rôle in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Gioachino Rossini’s Zelmira on 5 April 2019, as Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia at San Diego Opera in 2012

[Photograph by Ken Howard, © by San Diego Opera]

The title rôle in Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Zelmira will be sung by Spanish mezzo-soprano Silvia Tro Santafé, an uncommonly versatile singer whose American début as Cherubino in a Santa Fe—an apt setting!—production of Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro has been followed by too few appearances in the USA. Zelmira was originated in 1822 by Isabella Colbran, the singer for whom Rossini wrote some of his most iconic heroines and who became his wife a month after Zelmira’s première. The national origin that she shares with the rôle’s creator is an obvious aspect of Zelmira’s allure for Santafé. ‘Of course, as a Spanish singer I have a special interest in rôles created for Isabel Colbran!’ she declared. Not surprisingly, especially considering her superb bravura technique, Santafé also feels particular affection for Rossini’s music. ‘I have always felt [that] Rossini is the center of my singing. From the serious rôles—Arsace [in Semiramide], for example—and all the comic rôles I sing, which are not actually all that comic if you really think about the characters, I find these roots in all the music I sing.’ These roots, she intimated, provide the technical security that has enabled her to comfortably explore other repertory.

Earlier this year, Santafé sang her first Laura in Amilcare Ponchielli’s La Gioconda at Théâtre Royale de La Monnaie, an achievement that she credits to the technical foundation built upon her experience in Rossini rôles. ‘Laura is my first step into early verismo and has very direct demands from the very beginning of the rôle,’ the mezzo-soprano remarked. ‘La Gioconda is a drama packed with fast-moving dramatic situations, and the rôle reflects that.’ This is a trait that Laura and Zelmira have in common, she suggested. She continued, ‘Zelmira is also a quickly-unfolding drama, and the character of the singing and Rossini’s masterful writing take [Zelmira] through multiple situations. Sometimes, [the drama is] extremely intimate, as in a truly beautiful Duetto in Act One or Zelmira’s prison aria in the second act. Then, [in] the incredibly grand ensembles, the drive of Rossini’s rhythm and tempo creates overwhelming vocal excitement.’

A consummate mistress of opera’s grand passions, Santafé is ever cognizant that vocal control must govern even the most unbridled operatic emotions. ‘The discipline of Rossini’s coloratura helps me prepare for [the performances as] Principessa Eboli that I will sing in Madrid this year,’ she said. It is not merely Rossini’s translation of psychological drama into fiorature requiring specific technical mastery that makes the composer’s music a grounding force for Santafé, however. She summarized her process of learning Zelmira’s music with a statement that reveals much about the importance of Rossini repertory to her artistic identity. ‘Rossini’s beautiful long phrases became amplified later in Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi, and Ponchielli, which means [that] as a singer my approach to the drama and the vocal demands will always be influenced by my Rossini musical roots. No matter how distant [I roam], I always return.’

The company’s Zelmira’s credo might also be cited in an assessment of Washington Concert Opera. Repertory in WCO’s recent seasons has roamed as widely as Richard Strauss’s Guntram, Massenet’s Hérodiade, and Gounod’s Sapho, but performing Zelmira is a return to the bel canto roots that have resiliently anchored Washington Concert Opera in the nation’s notoriously unstable operatic humus for the past three decades.

In addition to Silvia Tro Santafé and Lawrence Brownlee, the cast for Washington Concert Opera’s performance of Rossini’s Zelmira includes mezzo-soprano Vivica Genaux as Emma, tenor Julius Ahn as Antenore, bass-baritone Patrick Carfizzi as Polidoro, and bass-baritone Matthew Scollin as Leucippo.

The performance will take place in Lisner Auditorium on the campus of The George Washington University at 7:00 PM (EDT) on Friday, 5 April 2019.

For more information and to purchase tickets for the performance, please visit Washington Concert Opera’s website.