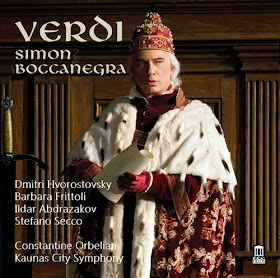

GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Simon Boccanegra—Dmitri Hvorostovsky (Simon Boccanegra), Barbara Frittoli (Amelia Grimaldi/Maria Boccanegra), Ildar Abdrazakov (Jacopo Fiesco/Andrea Grimaldi), Stefano Secco (Gabriele Adorno), Kostas Smoriginas (Pietro), Marco Caria (Paolo Albiani), Eglė Šidlauskaitė (Ancella), Kęstutis Alčauskis (Capitano); Kaunas State Choir; Kaunas City Symphony Orchestra; Constantine Orbelian, conductor [Recorded at the Kaunas Philharmonic, Kaunas, Lithuania, 1 – 7 August 2013; Delos DE 3457; 2 CDs, 129:55; Available from Delos, ClassicsOnlineHD, Amazon, Presto Classical, and major music retailers]

GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901): Simon Boccanegra—Dmitri Hvorostovsky (Simon Boccanegra), Barbara Frittoli (Amelia Grimaldi/Maria Boccanegra), Ildar Abdrazakov (Jacopo Fiesco/Andrea Grimaldi), Stefano Secco (Gabriele Adorno), Kostas Smoriginas (Pietro), Marco Caria (Paolo Albiani), Eglė Šidlauskaitė (Ancella), Kęstutis Alčauskis (Capitano); Kaunas State Choir; Kaunas City Symphony Orchestra; Constantine Orbelian, conductor [Recorded at the Kaunas Philharmonic, Kaunas, Lithuania, 1 – 7 August 2013; Delos DE 3457; 2 CDs, 129:55; Available from Delos, ClassicsOnlineHD, Amazon, Presto Classical, and major music retailers]

Captured in spacious sound with balances that occasionally seem artificial, this recording of Simon Boccanegra reunites several singers who have participated in revivals of the score at New York's Metropolitan Opera. This experience is evident in the performance preserved by Delos. On the podium, Constantine Orbelian presides with the assurance of one who knows and loves the score from cover to cover. He supports the singers instinctively but also neglects none of the oft-overlooked details of Verdi's orchestrations. In response to Orbelian's leadership, the strings of the Kaunas City Symphony often play with intimacy more typical of chamber music, their textures lean but full-bodied. The wind players also take care to blend their tones sonorously, their refinement not inhibiting the unleashing of torrents of sound when Verdi asks for them. The suspense of the Prologue's deceptively alluring opening scene is built to a crashing climax, and the mysterious sound world of Fiesco's great aria is conjured without distortion of the composer's prescribed rhythms. Here, Orbelian's acquaintance with Baroque repertory is beneficial: the ethereal atmosphere of Händel's Orlando is surprisingly close at hand. The very different moods of the successive duets in Act One are subtly but unmistakably limned by conductor and orchestra, and the monumental architecture of the Council Chamber scene is grandly but not excessively highlighted. Particularly in the Prologue and Act One, the singing of the Kaunas State Choir is an integral component of the success of Orbelian's approach to the score. The raw power of the choristers' singing in the public scenes is complemented by the carefully-managed blending of voices, especially in passages in which they are heard from offstage. Orchestra and chorus collaborate with Orbelian with the naturalness of friends assembled to make music for their own enjoyment. The conductor's tempi enable soloists, choristers, and instrumentalists alike to focus on giving of their best. Numbers like the magnificent duet for Simone and Amelia in Act Two are granted appealing lyrical flexibility but are not allowed to wallow in sentimentality. The prevailing qualities of this performance, shared by conductor, orchestra, and chorus, are unforced musicality and good sense.

In addition to the wonderful Kaunas orchestra and chorus, three native Lithuanian artists make valuable contributions to this performance of Simon Boccanegra. As Amelia's maid, mezzo-soprano Eglė Šidlauskaitė sings warmly and manages to convey sisterly concern despite the brevity of her part. Tenor Kęstutis Alčauskis is a flinty, strong-voiced Capitano, his proclamation of 'Cittadini! per ordine del Doge s'estinguano le faci e non s'offenda col clamor del trionfo i prodi estinti' in Act Three ringing with martial authority. Baritone Kostas Smoriginas is a stirringly incisive Pietro, a conspirator with a misguided but not unredeemable heart. The character is perhaps bullied by Paolo, but there is nothing weak about Smoriginas’s vocalism. Moreover, he displays considerable dramatic intelligence that marks him as a young singer to watch.

As portrayed by baritone Marco Caria, the wicked Paolo Albiani is a demonic fellow made all the more dangerous by how attractive he makes evil sound. In the opera’s Prologue, he voices the Allegro moderato 'L'atra magion vedete?.. de' Fieschi è l'empio ostello' with reptilian slyness, and he conducts his seditious affairs with solid intonation and unrelenting intensity. In the Act Two duet with Fiesco, he voices 'Me stesso ho maledetto!' vigorously. There are no regret or remorse in this Paolo as he is led to his well-deserved execution except for those of a man who has not accomplished as much mischief as he might have done. Caria's, too, is a name to remember.

Musically and dramatically, Jacopo Fiesco is one of Verdi's most demanding rôles for bass. Fiesco's hatred for Boccanegra has transformed him from a pillar of Genovese society into a broken man capable only of plotting revenge. Russian bass Ildar Abdrazakov gives the character an innate dignity that fosters a measure of sympathy for the old man. His scene and aria in the Prologue, 'A te l'estremo addio, palagio altero' and 'Il lacerato spirito del mesto genitore era serbato a strazio d'infamia e di dolore,' constitute one of Verdi’s most exquisite inspirations. Abdrazakov enunciates the recitative with great focus, and he phrases the aria eloquently. The concluding low F♯ lacks resonance, and his lowest notes are the weakest part of his singing throughout the performance. He unsparingly trades jabs with Boccanegra in their scene, and he haunts the Prologue like the specter of a restless wanderer. Abdrazakov's vocal steadiness—a trait too seldom heard in Fiesco's music—is especially welcome in Act One, in which he sings the duet with Gabriele with impressive sensitivity. He phrases the Sostenuto religioso, 'Vieni a me, ti benedico nella pace di quest'ora,' with genuine tenderness, and the contrast with his imperious singing in Fiesco's Act Two duet with Paolo could not be greater. In Act Three, Abdrazakov's pointed voicing of the throbbing Largo, 'Delle faci festanti al barlume cifre arcane, funebri vedrai,' is very touching, the line punctuated by the singer's easy rise to the top F. A few strange vowels notwithstanding, Abdrazakov uses text with near-native sophistication, but it is the voice that makes the greater impact. Other singers have made Fiesco's implacability more palpable, but few have sung his music more securely.

Gabriele Adorno is, in comparison with most of the mature Verdi's parts for tenor, a thankless rôle. Throughout much of the opera, he both is misled and misinterprets the situations in which he finds himself. He has some fantastic music, however, and uncomplicated musicality is the defining precept of Stefano Secco's performance on this recording. From his entrance in Act One, his bright timbre and straightforward interpretation of the rôle give pleasure even when the actual singing is less ingratiating. There is an engaging boyishness in his singing of 'Cielo di stelle orbato, di fior vedovo prato, è l'alma senza amor' in the duet with Amelia, and his top B♭s in unison with his beloved in 'Sì, sì dell'ara il giubilo' are tossed off with panache. Of a wholly different demeanor is Secco's singing in the duet with Fiesco, in which he voices the Allegro moderato section, 'Tu che lei vegli con paterna cura a nostre nozze assenti,' with distinction. The voice rings with impetuosity in the Council Chamber scene as Gabriele rashly accuses Boccanegra of abducting Amelia. Secco ably imparts the character's confusion and embarrassment as events he does not fully comprehend play out before him. He does not comply with Verdi's request that Gabriele should double Amelia's final trill in the scene, but he holds his own in the vast ensemble without forcing the voice too perilously. The Allegro sostenuto aria in Act Two, 'Sento avvampar nell'anima furente gelosia,' is passionately sung, and the simplicity and sincerity of the tenor's delivery of the aria’s Largo section, 'Cielo pietoso, redila, redila a questo core,' are unexpectedly poignant. In the subsequent duet with Amelia, Secco devotes an outpouring of lyrical tone to 'Parla, in tuo cor virgineo fede al diletto rendi.' Gabriele's trembling uncertainty as he contemplates murdering the sleeping Boccanegra in the opening pages of the Act Two finale is evinced by Secco's singing of 'Ei dorme!... Quale sento ritegno?' In the marvelous trio, another precious blossom of Verdi's genius, the ardor of Secco's singing of 'Perdon, perdon, Amelia, indomito geloso amor fu il mio' heightens the emotional impact of the scene. Finally knowing the truth about Amelia's parentage and past, Secco's Gabriele comforts both Amelia and the dying Boccanegra in Act Three with the compassion of a man who has at last recognized his destiny. Secco's voice is not a malleable, easily-produced instrument, but he is a shrewd singer who projects tones evenly and effectively. Ultimately, his heartfelt Gabriele is more gratifying than other tenors' self-conscious efforts at puffed-up heroics.

A versatile singer whose acclaimed operatic portrayals include rôles by Mozart, Donizetti, and Puccini, Italian soprano Barbara Frittoli follows in the tradition of singers such as Mirella Freni and Katia Ricciarelli, singers whose natural lyric voices were capable, when managed with caution, of successfully taking on parts requiring larger voices. Amelia's music is difficult to categorize: the tessitura is centered in the middle of the soprano range like that of a rôle written for a dramatic or spinto voice, but she also has trills—as does Wagner's Brünnhilde, of course. Like Secco, Frittoli manages her part in Simon Boccanegra without excessive strain. She starts Act One with a graceful but somewhat plain account of the aria 'Come in quest'ora bruna, sorridon gli astri e il mare!' Her top B♭ is secure, but the upper register often has a tremulousness that gives the voice a hard edge. In the duet with Gabriele, she soars to a blazing top B on 'gioia!' before voicing the Andantino, 'Vieni a mirar la cerula marina tremolante,' with compelling sensitivity. She and Secco combine artfully in 'Sì, sì dell'ara il giubilo,' the patina of her top B♭s blending well with the tenor's. The duet with Boccanegra is the beating heart of Act One, and Frittoli phrases 'Orfanella il tetto umile m'accogliea d'una meschina' and 'Padre! vedrai la vigile...figlia a te sempre accanto' with gleaming Italianate fervor, her long-held top B♭ cathartically crowning the duet’s final bars. Her top B♭ on 'Ferisci?' as she rushes to shield Boccanegra from his would-be assassins in the Council Chamber scene is explosive, but the terror and shame that shape her narrative in 'Nell'ora soave che all'estasi invita' are even more gripping. The crucial trills are more approximated than truly executed, but the effort is admirable. In the Act Two duet with Gabriele, Frittoli spins a silken thread of tone in 'Sgombra dall'alma il dubbio.' Her finest singing is in the trio in the Act Two finale, in which her plea for her dead mother's protection, 'Madre, che dall'empireo proteggi la tua figlia,' is deeply moving. Amelia's burden is the pain of finding her father only to lose him again, and Frittoli depicts a woman forever wounded by this pain. Hers is an imaginative portrayal only occasionally betrayed by vocal frailty.

The Boccanegra of Russian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky is a characterization heard in many of the world's important opera houses. A strikingly handsome man with one of the few legitimately significant baritone voices to have emerged in the past three decades, Hvorostovsky has gradually added the celebrated Verdi baritone rôles to his repertory as he felt that they became comfortable fits for his voice. In larger houses, he is sometimes forced to push his fine-grained instrument to ensure that he is heard, but recording a part like Boccanegra in studio enables him to sing without the necessity of projecting to the last row. In the Prologue in this recording, there is a suggestion of genuine surprise in his articulation of 'Suona ogni labbro il mio nome,' and his nuanced reading of the Andantino in the scene with Fiesco, 'Del mar sul lido tra gente ostile crescea nell'ombra quella gentile,' is insightful. Reluctant to ascend to the Doge's throne, not least after discovering the death of his dear Maria, this Boccanegra bows to the will of the people with humility. Hvorostovsky is resplendently in his element in the Act One duet with Amelia. He is almost playful in 'Dinne...alcun là non vedesti?' as he grows more certain that Amelia is his daughter. The expansiveness of his phrasing of 'Figlia! A tal nome palpito qual se m'aprisse i cieli'—is there any more heart-stopping melody in opera?—is evidence of the baritone's formidable breath control, and his soft top F—more piano than Verdi's ppp, admittedly—on the final voicing of 'Figlia!' is superb. The declamatory style in the Council Chamber scene does not come as naturally to Hvorostovsky, but he copes manfully, the voice sounding robust but not hard-driven. The pinnacle of his singing in Act Two is his bitter utterance of 'Doge! ancor proveran la tua clemenza i traditori?' This is seconded by a bracing account of 'Deggio salvarlo e stendere la mano all'inimico?' in the trio. Hvorostovsky's performance in Act Three is epitomized by his unexaggerated enacting of Boccanegra's death. Here, as throughout the performance on this recording, he sings the part on his own terms. They are terms that Verdi would surely have endorsed enthusiastically.

Simon Boccanegra has been a frequent visitor to the world's opera houses during the past decade, and this familiarity has bred the contempt of realizing that standards of Verdi singing have declined precipitously since the era—not so long ago—when the dedicated Verdian could hear Leonard Warren, Giuseppe Taddei, Tito Gobbi, and Cornell MacNeil as Boccanegra. The magnetism of Simon Boccanegra is such that a poor Boccanegra, Amelia, or Gabriele is more willingly endured than a poor Rigoletto, Gilda, or Duca di Mantova, but this Delos recording of Simon Boccanegra is a heartening reminder that the art of singing Verdi is injured but not dead. It is not perfect, but neither are the opera itself nor those who hear it.