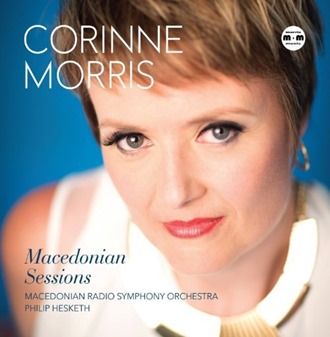

WOLDEMAR BARGIEL (1828 – 1897), MAX BRUCH (1838 – 1920), MANUEL DE FALLA (1876 – 1946), GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845 – 1924), JULES MASSENET (1842 – 1912), CORINNE MORRIS, ASTOR PIAZZOLLA (born 1921), CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS (1835 – 1921), PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840 – 1893), and JOHN WILLIAMS (born 1932): Macedonian Sessions—Corinne Morris, cello; F.A.M.E.’S. Macedonian Radio Symphony Orchestra; Philip Hesketh, conductor [Recorded in F.A.M.E.’S. Project Studio M1, Skopje, Macedonia, 29 June – 1 July 2013; Morris Music Productions MMP1307; 1 CD, 61:08; Available on CD and in digital form from Amazon UK]

WOLDEMAR BARGIEL (1828 – 1897), MAX BRUCH (1838 – 1920), MANUEL DE FALLA (1876 – 1946), GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845 – 1924), JULES MASSENET (1842 – 1912), CORINNE MORRIS, ASTOR PIAZZOLLA (born 1921), CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS (1835 – 1921), PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840 – 1893), and JOHN WILLIAMS (born 1932): Macedonian Sessions—Corinne Morris, cello; F.A.M.E.’S. Macedonian Radio Symphony Orchestra; Philip Hesketh, conductor [Recorded in F.A.M.E.’S. Project Studio M1, Skopje, Macedonia, 29 June – 1 July 2013; Morris Music Productions MMP1307; 1 CD, 61:08; Available on CD and in digital form from Amazon UK]

There is not in medicine, science, or religion any remedy to the maladies of men more restorative than music. Music has the capacity to comfort as neither the words nor the deeds of men can do, a capacity to, as Beethoven described it, go from heart to heart, undiluted and without need for translation or interpretation. There are also in music sparks that, when exposed to the proper elements, ignite resilience on a scale that obliterates adversities internal and external. The healing powers of music are epitomized both by gifted cellist Corinne Morris and by her remarkable disc Macedonian Sessions, so named because the disc was recorded in Skopje, Macedonia, with F.A.M.E.’S. Macedonian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Maestro Philip Hesketh. It is virtually impossible—and patronizing—to attempt to recreate with feeble words the ‘darkness visible’ into which Morris was plunged when a debilitating injury separated her from the cello, but the joy of her return to the instrument, facilitated by a corrective procedure developed for the treatment of athletes, sprints through every bar of Macedonian Sessions. There are a few moments on the disc in which the cellist’s intonation is not completely perfect, but there is not one stroke of her bow that does not reach the listener’s heart with a jubilant, profoundly grateful cry of ‘I am back!’

Max Bruch’s Kol Nidrei (Opus 47) is the most substantial piece on Macedonian Sessions, and it offers at the disc’s start a wonderfully complete overview of Morris’s artistry. Demanding both virtuosity and expressivity, the Protestant Bruch’s 1880 setting of Jewish themes, taking its title from the Aramaic prayer recited at the start of Yom Kippur, is played by Morris with vitality and emotional sincerity. Bruch’s intentions in composing Kol Nidrei were solely musical rather than religious or sentimental, and Morris’s avoidance of saccharine affectation enhances the raw impact of the music. Camille Saint-Saëns’s Allegro Appassionato (Opus 43) is also a piece in which feeling and fleet passagework are combined with ingenuity, and Morris brings an appealing Gallic airiness to her performance of the piece, complemented by the effervescent charm evinced by Hesketh and the Macedonian musicians, who prove to be wonderful, infallibly musical companions on Morris’s journey throughout Macedonian Sessions.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Nocturne (Opus 19, No. 4) is a sublime masterpiece in miniature, and Morris’s dulcet but dramatic style finds an ideal outlet in the piece, the cellist’s burnished tones extracting every thread of meaning from the tapestry of the music. Adapted from the second movement of the composer’s Opus 11 String Quartet No. 1, the famously plaintive principal theme of Tchaikovsky’s Andante Cantabile, here played in an arrangement that honors its origins in the Quartet, is derived from Russian folksong. So poignant is Tchaikovsky’s representation in sound of the collective Russian soul that it is recorded in the composer’s own correspondence that Leo Tolstoy was moved to tears by hearing the Andante Cantabile for the first time. His response to hearing Morris’s shimmering performance of that haunting subject might have been the same, his tears blending with exclamations of joy at the rebirth of so valuable an artist. Morris’s vibrato gently caresses melodic lines rather than obscuring pitches, and, especially in the Tchaikovsky selections, she finds the emotions within the music instead of arbitrarily establishing moods and then molding her performances to adhere to them.

The name Woldemar Bargiel is now virtually unknown even to curious musicians, and were he not Clara Schumann’s half-brother he might be wholly forgotten. The quality of Bargiel’s Adagio (Opus 38), played with sonorous tone and emotive phrasing by Morris and the orchestra, prompts curiosity about Bargiel’s work, not least his seldom-performed String Quartets. A well-crafted piece that validates the influence of Bargiel’s acquaintance with the work of his half-sister and her husband, Robert Schumann, as well as Felix Mendelssohn and even the young Brahms, the Adagio receives from Morris and her Macedonian colleagues a reading of depth and heartfelt intensity, the orchestra’s strings creating a halo of sound in the center of which Morris’s playing gleams.

The iconic Theme from John Williams’s score for Steven Spielberg’s Holocaust film Schindler’s List, so memorably played on the motion picture soundtrack by Itzhak Perlman, has rightly transcended the context of the film and assumed a place in the concert repertory. Hopefully, Morris’s performance on Macedonian Sessions will inspire other cellists to add the piece to their repertories. Like the Hebraic themes in Bruch’s Kol Nidrei, the indelible melody of Williams’s Schindler’s List Theme possesses a bizarrely disquieting dignity, and there is an almost Klezmer-like cadence to Morris’s playing. Through the resounding warmth of her cello, an 1876 instrument by Claude Augustin Miremont, the contrasting optimism and pathos of the music are subtly but resolutely disclosed. Here and throughout the music on Macedonian Sessions, Morris’s marvelous bowing technique is allied with an intuitive grasp of the structures of each piece, the latter being a trait that Hesketh shares.

Originally intended as the slow movement for a sonata that was never completed, Gabriel Fauré’s C-minor Elégie (Opus 24) was written for cello and piano and later orchestrated by the composer. The inimitable Catalan cellist Pau Casals premièred the orchestrated version, and Morris’s playing of the piece on Macedonian Sessions brings to mind the rhythmic solidity and polished-garnet timbre that characterized Casals’s mature artistry. The contrast between the bittersweet wistfulness of the piece’s first subject and the red-blooded energy of the tempestuous central section is heightened by the instinctive differentiation of Morris’s approach, her varied playing looking far beyond mere changes of tempo. The familiar strains of the gorgeously lyrical ‘Méditation’ from Jules Massenet’s opera Thaïs are no less effective when played on the cello than on the violin. Indeed, so lovely is Morris’s playing of the piece’s ethereal harmonics that only the most attentive of casual listeners might perceive the change in instrumentation. The French portion of Morris’s soul soars in her graciously idiomatic playing of the music of Fauré and Massenet.

Originally written for the composer’s beloved bandoneón, Astor Piazzolla’s Oblivion transforms the Skopje studio and the listener’s imagination into a deserted bar in Buenos Aires. It is just after closing, when the sounds of a new day begin to disturb the weary barkeep’s reverie. Morris’s bewitching performance of Piazzolla’s music steals in with the determined playfulness of day chasing night into the corners, illuminating the dark peripheries of the piece. The transcription of the ‘Ritual Fire Dance’ from Manuel de Falla’s El amor brujo employed by Morris is no less effective in its conjuring of a specific but universal atmosphere. The earthy qualities of de Falla’s witty tone painting scintillate in Morris’s performance, and her efforts are seconded by particularly cogent work from Hesketh and the young Macedonian musicians.

The arrangement for cello and orchestra of Morris’s own song ‘Un’ ultima volta’ has an unapologetic Romantic lushness that transports the listener to Italy in the 1950s, to windswept towns by the Mediterranean and piazze baked by the sun. Composed for voice and orchestra whilst Morris was unable to play the cello, the song’s gentle melancholy is beautifully conveyed by the unmistakably ‘vocal’ cello line. Like Bargiel’s Adagio, ‘Un’ ultima volta’ whets the appetite for more of Morris’s compositions. Not surprisingly, there is an aura of authoritativeness to her playing of ‘Un’ ultima volta,’ but this is true of her performances of every selection on the disc. In filling the fluid melodic lines of the song, she becomes the Renata Tebaldi of the cello, the reserves of power bolstering the tone always audible but never obtrusive. This is music that embraces late-Romantic, Italianate tonalism as affectionately as Gian Carlo Menotti did in Amelia al ballo and The Last Savage, and Morris plays as enjoyably as she composed.

Macedonian Sessions is in many ways as much a statement of individual triumph as it is a musical experience. Above all, though, it is a love story told in eleven pieces via which a master musical communicator regains and rejuvenates her power of speech. As spoken by Corinne Morris and her cello, music is a language not of words but of responses to life both too intimate and too intricate to be verbalized. For all of the egotism, vanity, and cut-throat competition that afflict today’s Performing Arts community, it remains a quintessentially Existential environment in which, as John Donne might have suggested, one artist’s incapacitation is a loss inflicted upon all artists and laypeople alike. Not least owing to Macedonian Sessions, Corinne Morris’s reunion with the cello is likewise a felicitous occasion that enriches the Arts beyond measure. Solely from a musical perspective, though, few ‘Welcome Back’ celebrations are as delectable as Macedonian Sessions.