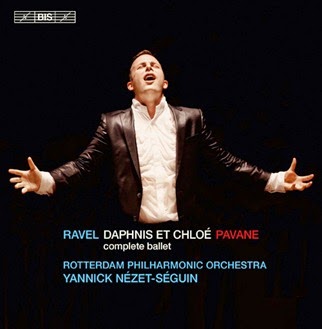

MAURICE RAVEL (1875 – 1937): Daphnis et Chloé [complete ballet] and Pavane pour une infante défunte—Netherlands Radio Choir (Daphnis et Chloé); Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra; Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conductor [Recorded in De Doelen Hall, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, in June 2012 (Daphnis et Chloé) and March 2014 (Pavane pour une infante défunte); BIS Records BIS-1850; 1 CD, 63:27; Available from ClassicsOnlineHD, Amazon, jpc, Presto Classical, and major music retailers]

MAURICE RAVEL (1875 – 1937): Daphnis et Chloé [complete ballet] and Pavane pour une infante défunte—Netherlands Radio Choir (Daphnis et Chloé); Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra; Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conductor [Recorded in De Doelen Hall, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, in June 2012 (Daphnis et Chloé) and March 2014 (Pavane pour une infante défunte); BIS Records BIS-1850; 1 CD, 63:27; Available from ClassicsOnlineHD, Amazon, jpc, Presto Classical, and major music retailers]

In an age in which acclaim often has little to do with quality, how does one make one’s mark as a conductor without betraying individuality and one’s own unique cultural identity? With Classical Music ever more a commodity rather than a community, a young musician is sometimes required to devote greater attention to the business of making a career rather than following where his musical instincts lead. Sadly, colleagues are competitors in the nonsensical but perhaps necessary game of garnering ‘likes’ and ‘followers’ on social media rather than kindred spirits to be cherished and supported. This life of a serious young artist in the Twenty-First Century is a crushing business that scoffs at the notion of building and maintaining a successful career on one’s own terms, but this is what Québécois conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin has done and continues to do. He is a master of the trappings of modern notoriety, but his love for music and respect for those with whom he collaborates in creating it are joyously apparent in every performance over which he presides. A recent, already infamous Saturday matinée performance of Verdi’s Don Carlo at the Metropolitan Opera exemplified Maestro Nézet-Séguin’s defining ethos as a conductor. With a host of challenges tearing the performance apart, he calmly used his baton as a needle to reinforce the opera’s seams, sewing a golden thread into the tattered fabric of a poorly-fitted garment. Through the struggles, the dignity of Serafin, the grand but heartfelt gestures of Giulini, and the sweep of Karajan were present in his pacing of the gargantuan score. Too sensitive a musician and, by all accounts, too kind a man to ignore his colleagues’ distress, he found in Verdi’s music the strength to uplift the performance and hold back the tide of negativity that threatened to flood stage, pit, and auditorium. These were not actions intended to inspire hashtags and retweets: they were a committed musician’s responses to his sense of camaraderie with fellow artists. These were the actions of an important conductor for whom greatness is measured not by social media chatter or even by applause but by the knowledge of having given his all to the composer, his colleagues, and his audience.

This recorded performance of Maurice Ravel’s ballet Daphnis et Chloé, composed between 1909 and 1912, is a product of Maestro Nézet-Séguin’s directorship of the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, and the quality of the music-making on this disc is evidence of the serendipitous symbiosis of the relationship between conductor and orchestra. Throughout the performance, the orchestral personnel play sonorously and with legitimate Gallic sophistication, personified by the slyly seductive solo lines of flautist Juliette Hurel. Ravel christened Daphnis et Chloé as a ‘symphonie choréographique,’ and Maestro Nézet-Séguin’s pacing of the piece on this recording is decidedly more symphonic than balletic in scope. Commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev and premièred by his Ballets Russes at Paris’s Théâtre du Châtelet on 8 June 1912, the score is an inventive hybrid, the offstage, wordless chorus—here the Netherlands Radio Choir, creating eerily atmospheric effects with superbly-blended singing—employed with the sort of enigmatic beauty familiarized by similar writing in the celebrated Méditation in Massenet’s Thaïs. A particular strength of Maestro Nézet-Séguin’s work in general is his affinity for preserving lean textures even in passages with dense orchestrations, enabling details to emerge with uncommon clarity. Compared with the classic account led by Pierre Monteux, who conducted the score’s première, Maestro Nézet-Séguin’s recording of Daphnis et Chloé is notable for his measured approach, his tempi indicative of a profound understanding of the score’s lush sensuality. Maestro Nézet-Séguin’s concept of Daphnis et Chloé is one of sultry, unfulfilled desires rather than noisy but ultimately meaningless climaxes. In this performance, the work’s three parts are presented as unique but interrelated paragraphs in a single narrative, and commitment to Maestro Nézet-Séguin’s vision seems to be shared by every musician under his direction.

Launching the Première Partie, the opening whispers of the Introduction (Lent – Très modéré) arise hesitantly, almost uncertainly, from primordial silence, the effect not unlike that of the beginning of Wagner’s Das Rheingold. Maestro Nézet-Séguin encourages beautiful rather than overtly dramatic playing, enhancing the music’s latent eroticism. This is especially true in the Danse religieuse (Modéré) and Danse des jeunes filles (Vif), the rhythmic profiles of which are shaped by attention to sustaining mood without sacrificing textural lucidity. The masterfully-contrasted strains of the Danse grotesque de Dorcon (Vif – Plus modéré – Très modéré – Pesant), Danse légère et gracieuse de Daphnis (Assez lent – Animé – Vif), and Lyceion entre (Lent – moins lent – Très libre)—decidedly sounds of the Twentieth Century—are given very distinct but strangely complementary auras, each tempo change heightening the restlessness of Ravel’s harmonic centers of gravity. The shimmering Nocturne is performed with a disquieting simplicity that seems both supplicating and sinister, the genius of Ravel’s writing for the orchestra never more perceptible.

Maestro Nézet-Séguin paces the Interlude that opens the ballet’s Deuxième Partie with eloquence derived from rhythmic freedom, and the Rotterdam Philharmonic musicians respond with unmistakably affectionate playing. The ferocity of the Danse guerrière is startlingly realized by both conductor and orchestra, but the poetry of the Danse suppliante de Chloé is recited with equal fluency in Ravel’s compositional idiom. A century after the music was first performed, the young conductor and his Rotterdam musical family communicate both the emotions that have become familiar through lauded performances and recordings and passions unique to this performance.

Perhaps the most familiar music in Daphnis et Chloé is Ravel’s Impressionistic representation of dawn in ‘Lever du jour’ in the ballet’s Troisième Partie. In this performance, the restoration of light to the slumbering earth is in Maestro Nézet-Séguin’s handling a genuine musical catharsis. The colors that he extracts from the orchestra scintillate in the burgeoning light of Ravel’s depiction of the awakening world, a symbolic partner of the music of the ballet’s first scene. The expansive sentimental canvas of the Pantomime (Les amours de Pan et Syrinx) is filled with stirring imagery drawn directly from Ravel’s score. Throughout the performance, the string, woodwind, and percussion playing is luxuriously beautiful, but the musicians reach new peaks of virtuosity in the final Danse générale (Bacchanale). Here, too, Maestro Nézet-Séguin’s dual attention to the singular needs of the Bacchanale and the cumulative impact of the score is discernible. The jubilant conclusion of the ballet inspires an exhibition of the artistry possible only with complete comfort with and dedication to the music.

Originally composed for piano solo in 1899, orchestrated by the composer in 1910, and ultimately denounced owing to what he perceived as an unacceptably pervasive indebtedness to Emmanuel Chabrier, the Pavane pour une infante défunte is understandably one of Ravel’s most enduringly popular works, its Spanish flavor produced by some of the same ingredients that spice Boléro and L’heure espagnole. Horn player Martin van de Merwe’s solo lines are the foundation upon which Maestro Nézet-Séguin and the Rotterdam Philharmonic players form a traversal of the piece that evinces deep feeling without wallowing in dumb-show pathos. As in their performance of Daphnis et Chloé, this team’s playing of Pavane pour une infante défunte is distinguished by ebullient musicality that cascades through Ravel’s score.

Recordings of Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé and Pavane pour une infante défunte are numerous, and many of them preserve the work of conductors and orchestras whose endeavors to fashion unique interpretations of these great scores led them away from rather than into the music. This recording by the Rotterdam Philharmonic and Yannick Nézet-Séguin, whose tenure as the orchestra’s Principal Conductor will end in 2018, is unique in its fidelity to Ravel’s inspiration. How wonderful it is to hear on this disc an honest rendering of this stimulating music rather than idiosyncratic variations on Ravel’s unforgettable themes. Careers are changeable creatures, but Art, when executed at this level, is eternal.