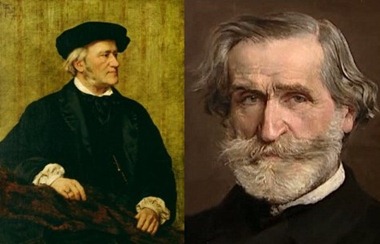

The bicentennials of the births of both Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner will be celebrated in 2013. One way in which Voix des Arts will mark these milestones will be with lists of various individuals’—artists', critics, and laypeople—personal selections of the finest recordings of these remarkable composers’ operas. This inaugural list presents the author’s selections, which are based upon personal, occasionally idiosyncratic, ideals of Verdi and Wagner performance. Ordering is random rather than indicative of any ranking or preference.

GIUSEPPE VERDI

(10.10.1813 – 27.01.1901)

- La Traviata – Maria Callas, Cesare Valletti, Mario Zanasi; Nicola Rescigno [Live performance, Covent Garden, 20.06.1958; various labels] This Covent Garden Traviata is, in so many ways, the quintessential Verdi recording. At its center is the Violetta of Maria Callas, one of the most compelling creations of one of the 20th Century’s greatest artists. Cesare Valletti, a tenor of uncompromising elegance, perhaps possessed a voice somewhat small for singing Verdi roles in a large house. Mario Zanasi, too, was not endowed by nature with the vocal amplitude typically heard in Verdi baritone roles. Alongside Callas, however, both gentlemen give performances that have never been surpassed. The scene in which Mr. Zanasi’s Germont pleas with Ms. Callas’s Violetta for her to abandon Alfredo for the good of her lover’s sister’s good name is in this author’s opinion the single greatest recorded example of Verdi’s art.

- Aida – Giannina Arangi-Lombardi, Aroldo Lindi, Maria Capuana, Armando Borgioli, Tancredi Pasero, Salvatore Baccaloni; Lorenzo Molajoli [Studio recording made at La Scala, 1928; various labels] Remarkably, two recordings of Aida were made at La Scala in 1928 (as was also the case in 1930 with Il Trovatore: see below), documenting that house’s desire to capitalize upon electrical recording technology to record the age’s great Verdi singers—and the desires of competing record labels to stock their archives with the sounds of idiomatic Italian singing. Among several fine performances, it is the Aida of Giannina Arangi-Lombardi that is the legendary performance in this recording. The beauty, power, and absolute security of her voice, allied with straightforward but never simplistic dramatic instincts, make Ms. Arangi-Lombardi an ideal Aida; and one who deserves to be better remembered.

- Simon Boccanegra – Lawrence Tibbett, Elisabeth Rethberg, Giovanni Martinelli, Ezio Pinza, Leonard Warren; Ettore Panizza [Live performance, Metropolitan Opera, 21.01.1939; various labels] Boccanegra has been well served in New York, at least until recent years, and this 1939 broadcast represents the Metropolitan’s standards at their highest. Few baritones have shown the affinity for Verdi’s music displayed by Lawrence Tibbett at his best, and his Boccanegra is a complicated, vocally sumptuous portrait. Ms. Rethberg, effective in a wide repertory, is a poised Maria. Mr. Martinelli, stirring in this performance, was the Adorno of choice for a generation of opera-goers. Mr. Pinza as Fiesco and the young Mr. Warren as Paolo are paragons of Verdi singing.

- Il Trovatore – Carlo Bergonzi, Leontyne Price, Fiorenza Cossotto, Piero Cappuccilli, Ivo Vinco; Oliviero de Fabritiis [Live performance, Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires, 06.1969; various labels] Few sopranos have been more naturally suited to the music of Verdi than Leontyne Price. It was as Leonora in Il Trovatore that she made her debut at the Metropolitan, and when she retired from its stage more than two decades later, her Aida remained a performance of considerable power. This Trovatore from Buenos Aires finds Ms. Price at the height of her powers, taking every challenge in stride. Mr. Bergonzi does not storm the heavens like Merli, Pertile, or Corelli, but he effectively reminds the listener that Leonora says that Manrico has descended from heaven. Ms. Cossotto, Mr. Cappuccilli, and Mr. Vinco are captured at their best in a performance that quickens the pulse and touches the heart.

- Il Trovatore – Francesco Merli, Bianca Scacciati, Giuseppina Zinetti, Enrico Molinari, Corrado Zambelli; Lorenzo Molajoli [Studio recording made at La Scala, 10.1930; various labels] Two recordings of Trovatore were made at La Scala within the space of a few days in October 1930. This performance preserves the Manrico of Francesco Merli, one of Italy’s greatest dramatic tenors and the first Calaf in Puccini’s Turandot to be heard in Britain and Australia. His Manrico is a dramatic firebrand, the voice ringing out impressively across the years. His colleagues do not quite reach his level of accomplishment, though Ms. Scacciati is one of the most interesting Leonoras on records.

- Il Trovatore – Aureliano Pertile, Maria Carena, Irene Minghini-Cattaneo, Apollo Granforte, Bruno Carmassi; Carlo Sabajno [Studio recording made at La Scala, 10.1930; various labels] The raison d’être for La Scala’s second 1930 Trovatore recording was Aureliano Pertile, and his Manrico deserved to be recorded for posterity. The uniquely bronzed timbre is evident in every phrase. Ms. Minghini-Cattaneo’s Azucena is a justifiably famous performance, a stinging portrait of an unhinged woman seeking revenge. Phenomenal, too, is Apollo Granforte’s Conte di Luna, a credibly duplicitous and serenely-sung performance by one of the greatest Italian baritones of the 20th Century.

- Falstaff – Giuseppe Valdengo, Herva Nelli, Teresa Stich-Randall, Antonio Madasi, Frank Guarrera, Nan Merriman, Cloë Elmo; Arturo Toscanini [Compendium of NBC broadcast performances of 01 and 04.04.1950; Sony/BMG/RCA] Arturo Toscanini’s series of Verdi broadcasts for NBC shaped Americans’ perceptions of Verdi’s operas throughout the 1940s and ‘50s. This Falstaff is one of the most consistently delightful performances among Toscanini’s NBC broadcasts. None of the singers is among the greatest Verdi singers of the era, but as an ensemble they achieve precisely the comic timing and emotional bite that Verdi’s valedictory masterpiece requires.

- La Forza del Destino – Maria Caniglia, Galliano Masini, Carlo Tagliabue, Ebe Stignani, Saturno Meletti, Tancredi Pasero; Gino Marinuzzi [EIAR Torino studio recording, 1941; Warner/Fonit Cetra] Few performances of La Forza del Destino convey the force of destiny as grippingly as this recording. Ms. Caniglia was an inconsistent singer, but her Leonora is vastly more interesting and moving than many better-sung performances. Mr. Masini, Mr. Tagliabue, Ms. Stignani, and Mr. Meletti are found at their best. Tancredi Pasero, rivaled as an idiomatic singer of Verdi bass roles only by Ezio Pinza, is the definitive Guardiano.

- Simon Boccanegra – Tito Gobbi, Victoria de los Ángeles, Giuseppe Campora, Boris Christoff, Walter Monachesi; Gabriele Santini [Studio recording, Rome, 1957; EMI] Never admired for its engineering or sound quality, this Boccanegra is nevertheless a legitimate benchmark both in the history of the opera and in the Verdi discography. Tito Gobbi lacked the prodigious vocal resources of Tibbett or Warren, but the sensitivity and ambiguity that he brings to his depiction of the delicate balance between Boccanegra’s public and private personas is magnificent. It is, furthermore, an important, extraordinary piece of singing. Ms. de los Ángeles is perhaps not as well remembered as a Verdian as she deserves to be: no other Maria on records achieves the focus, dramatic perfection, technical command, and sheer beauty exhibited by Ms. de los Ángeles. Mr. Campora is lightweight for Adorno but sings with absolute commitment. As recorded, Mr. Christoff sometimes sounds as though he is singing through gauze. He is the finest Fiesco on records by a considerable margin, however, his singing of ‘Il lacerato spirito’ crowning a superb performance.

- Don Carlo – Bruno Prevedi, Leyla Gencer, Fiorenza Cossotto, Sesto Bruscantini, Nicolai Ghiaurov, Luigi Roni; Fernando Previtali [Live performance, Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, 24.04.1968; various labels] This is an overlooked gem in the Don Carlo[s] discography. Not included among the ranks of the greatest tenors, Mr. Prevedi was an unfailingly musical singer and, in this performance, is a fine Don Carlo. Ms. Cossotto, Mr. Ghiaurov, and Mr. Roni give enjoyable performances, and it is wonderful to hear Mr. Bruscantini in a ‘substantial,’ serious role. It is the Elisabetta of Leyla Gencer that should be heard by every admirer of Verdi’s music, however. This is a woman—every inch a queen—whose passions boil. Her performance of ‘Tu che la vanità’ is an example of Verdi singing of the highest order.

RICHARD WAGNER

(22.05.1813 – 13.02.1883)

- Tristan und Isolde – Jon Vickers, Birgit Nilsson, Ruth Hesse, Bengt Rundgren, Walter Berry; Karl Böhm [Live performance, Chorégies d’Orange, 07.07.1973; various labels] There are rare occasions in opera on which the stars, celestial and musical, align in perfect arrangement, and this Orange Tristan und Isolde is one of those occasions. Ms. Nilsson and Mr. Vickers did not often encounter one another as Isolde and Tristan, and this is arguably the finest document of that infrequent union. Ms. Hesse is an unsung heroine of Wagner singing in the 20th Century, her ironclad technique and beautiful voice having contributed to many great performances. Mr. Rundgren and Mr. Berry offer alert, involved performances. Maestro Böhm was an undoubted master of this score, and this performance finds him near his best. It is a pity about the Mistral, but it was perhaps inevitable that even Nature would be swept along by this performance.

- Götterdämmerung – Kirsten Flagstad, Max Lorenz, Ludwig Weber, Alois Pernerstorfer, Josef Herrmann, Hilde Konetzni, Elisabeth Hönger; Wilhelm Furtwängler [Live performance, Teatro alla Scala, 04.04.1950; various labels] Ms. Flagstad may have been past her best at the time of this final installment of the celebrated 1950 La Scala Ring, but the grandeur of the voice was untouched by the years. With an uncommonly distinguished cast, Maestro Furtwängler presides over a performance that, according to his correspondence with his wife, he considered one of the pinnacles of his career.

- Die Walküre – Helen Traubel, Astrid Varnay, Friedrich Schorr, Lauritz Melchior, Kerstin Thorborg, Alexander Kipnis; Erich Leinsdorf [Live performance, Metropolitan Opera, 06.12.1941; various labels] One of the most famous broadcasts in Metropolitan Opera history, this performance introduced the world to Astrid Varnay, whose Brünnhildes at Bayreuth a decade later would usher in a new age of Wagner singing. Here singing Sieglinde, Ms. Varnay gives a glorious performance. Ms. Traubel was the Metropolitan’s homegrown stand-in after Kirsten Flagstad returned to Norway when World War II threatened to separate her from her husband indefinitely. She was an important singer and a great Brünnhilde in her own right, and the beauty of her Wagner singing is often revelatory. Otherwise, this performance displays the strength of the Metropolitan’s Wagner wing during Edward Johnson’s administration.

- Tannhäuser – Lauritz Melchior, Kirsten Flagstad, Kerstin Thorborg, Herbert Janssen, Emanuel List; Erich Leinsdorf [Live performance, Metropolitan Opera, 04.01.1941; various labels] Mr. Melchior was a near-continuous presence in the Metropolitan’s Wagner productions from his debut (as Tannhäuser) in 1926 until his final performance (as Lohengrin) in 1950. The high tessitura of Tannhäuser’s music has defeated many Heldentenors, but Mr. Melchior encounters few difficulties in this performance—a remarkable feat considering that, within six weeks, he sang Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, Tristan, Siegmund, and both Siegfrieds at the Metropolitan! It was Ms. Flagstad who ‘carried the honors’ in this performance according to Musical America, however, and her singing of Elisabeth’s Prayer is ravishing. No one disappoints. Of how many Tannhäuser performances can that be said?

- Lohengrin – Lauritz Melchior, Lotte Lehmann, Marjorie Lawrence, Friedrich Schorr, Emanuel List, Julius Huehn; Artur Bodanzky [Live performance, Metropolitan Opera, 21.12.1935; various labels] Mr. Melchior’s Lohengrin was a celebrated portrayal, and he is at his best in this broadcast. The other male cast members hold up their ends of the musical bargain, but the incomparable qualities of this performance are found in the exquisite singing and dramatic encounters of Ms. Lehmann’s Elsa and Ms. Lawrence’s Ortrud.

- Siegfried – Lauritz Melchior, Kirsten Flagstad, Friedrich Schorr, Karl Laufkötter, Eduard Habich, Kerstin Thorborg, Emanuel List; Artur Bodanzky [Live performance, Metropolitan Opera, 30.01.1937; various labels] This performance, too, finds Mr. Melchior at his best, voicing Siegfried with sterling technique and a voice of near-ideal proportions for the role. Mr. Laufkötter and Mr. Habich offer appropriately oily characterizations. Mr. Schorr, never heard in America on the form that electrified Europe, is nonetheless a bracingly eloquent Wanderer. Brünnhilde has less to do in Siegfried than in Walküre or Götterdämmerung, but no Brünnhilde on records awakens more thrillingly than Ms. Flagstad, who greets her conqueror with opulence worthy of a daughter of Wotan.

- Siegfried – Ludwig Suthaus, Martha Mödl, Ferdinand Frantz, Julius Patzak, Alois Pernerstorfer, Margarete Klose, Josef Greindl; Wilhelm Furtwängler [Live performances, RAI Roma, 10 – 11.1953; EMI] Three years after his pioneering Ring at La Scala, Maestro Furtwängler returned to Italy to present the Cycle in concert performances recorded for broadcast by Italian radio. This Siegfried preserves a rare performance of the title role by Mr. Suthaus, perhaps best remembered as a Wagnerian for his Tristan opposite Ms. Flagstad’s Isolde in her landmark studio recording. Siegfried was not an especially congenial part for Mr. Suthaus, but the level of accomplishment that he achieves is a testament to his abilities. All the cast rise to the occasion, but Martha Mödl’s Brünnhilde is a rightfully acclaimed performance, a worthy record of the work of a true mistress of Wagner’s music.

- Parsifal – Günther Treptow, Anny Konetzni, Ludwig Weber, Paul Schöffler, Hans Braun, Adolf Vogel; Rudolf Moralt [Live performance, Vienna Radio, 01.10.1948; various labels] Maestro Moralt presided over this Parsifal and an interesting Ring for Vienna radio in the days before the Wiener Staatsoper reopened after World War II. In this performance, some of the most celebrated Wagner singers of the post-War years are heard at their peaks, not least Ludwig Weber and Paul Schöffler. Ms. Konetzni’s wild, searching Kundry is fascinating, and Mr. Treptow’s Parsifal has the security that so many Parsifals lack. Maestro Moralt, a nephew of Richard Strauss, is an impressive, insightful, and undervalued conductor who knows and avoids the pitfalls of Parsifal.

- Das Rheingold – George London, Kirsten Flagstad, Set Svanholm, Paul Kuen, Gustav Neidlinger, Claire Watson, Waldemar Kmentt, Eberhard Wächter, Jean Madeira, Walter Kreppel, Kurt Böhme; Sir Georg Solti [Studio recording, 1958; DECCA] Sir Georg Solti, John Culshaw, and an unmatched cast launched DECCA’s ambitious project of recording Wagner’s Ring in studio with this Rheingold, the trump card of which was the luring of Kirsten Flagstad to sing Fricka. Whatever reservations she and her colleagues may have had are erased by the results that she achieved. The voice is diminished even from the form of her final Metropolitan performances as Gluck’s Alceste six years earlier, but Ms. Flagstad intones a towering, magisterial Fricka whose blandishments to Wotan cannot be ignored. Mr. London sings exhilaratingly, greeting Walhalla with ripping panache. All the cast perform their tasks with relish. Whatever the virtues of the Solti Ring as a whole, this Rheingold is a superb achievement.

- Die Walküre – Gertrude Grob-Prandl, Helene Werth, Ludwig Hofmann, Torsten Ralf, Georgine von Milinkovic, Herbert Alsen; Robert E. Denzler [Live performance, Victoria Hall, Geneva, 04.05.1951; various labels] This Walküre was planned as a staged performance, but the destruction by fire of the theatre in which it was to be played necessitated a change of venue and conversion to a concert performance. Misfortune thus produced a fantastic recording of Walküre, a performance built around the stunning Brünnhilde of Gertrude Grob-Prandl. Ms. Grob-Prandl produces a wall of sound that surprises with its security, accuracy, and brilliance at the extreme top. Ms. Werth contributes a refreshingly forthright Sieglinde, voiced with considerable beauty. Mr. Ralf, criticized in New York for lacking the easy upper register for roles like Tannhäuser and Walther von Stolzing, finds a comfortable tessitura in Siegmund’s music and sings manfully. Mr. Hofmann, Ms. von Milinkovic, and Mr. Alsen are familiar from Wagner performances throughout German-speaking Europe, and they contribute meaningfully to this Walküre. Maestro Denzler, who conducted at Bayreuth and led the first performance of Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler, proves a very gifted leader of Walküre, presiding over a performance that gives far more pleasure than many performances featuring more famous casts.

![Mezzo-soprano Marie-Nicole Lemieux (Cesare) [Photo by Denis Rouvre] Mezzo-soprano Marie-Nicole Lemieux (Cesare) [Photo by Denis Rouvre]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-Wx9WwsdT78A/UNimWqZguII/AAAAAAAABIc/wuRbayGdXRc/Marie_Nicole_Lemieux_by_Denis_Rouvre%25255B5%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![Harpsichordist Jory Vinikour [Photo by Kobie van Rensburg, 2008] Harpsichordist Jory Vinikour [Photo by Kobie van Rensburg, 2008]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-BnqBraDNxFg/UKRtoP4OIvI/AAAAAAAABGM/H1xATWPIHMk/Jory-Vinikour-1-by-Kobie-van-Rensbur.jpg?imgmax=800)

![Ebenezer Lutheran Chapel [Photo by Bill Fitzpatrick, 2012] Ebenezer Lutheran Chapel [Photo by Bill Fitzpatrick, 2012]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/-r6xCxXUHdpw/UKRtoqYhVnI/AAAAAAAABGU/BbsAgE_6T38/Ebenezer_Lutheran_Chapel_Bill_Fitzpa.jpg?imgmax=800)

![The Complete Harpsichord Works of Rameau - Jory Vinikour, harpsichord [Sono Luminus DSL-92154] The Complete Harpsichord Works of Rameau - Jory Vinikour, harpsichord [Sono Luminus DSL-92154]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/-1bptry_YajU/UG6FdPhi0_I/AAAAAAAABEc/z7mqrDSdXl0/Vinikour_Rameau_CD_Cover%25255B5%25255D.jpg?imgmax=800)

![Sébastien Guèze as Gounod's Roméo at FGO [Photo by Gastón de Cárdenas, FGO] Sébastien Guèze as Gounod's Roméo at FGO [Photo by Gastón de Cárdenas, FGO]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-7xyK4MAHzY0/UE_n3MlDJ8I/AAAAAAAABDU/ozvon9QPpbc/Gueze_Romeo_FGO_Gaston_de_Cardenas6.jpg?imgmax=800)